%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#E67E22', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085', 'tertiaryColor': '#E67E22', 'fontSize': '13px'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph "Threat Actors by Capability"

direction TB

NS[Nation States<br/>Highest skill, unlimited resources<br/>Espionage, sabotage]

CC[Cybercriminals<br/>High skill, profit-motivated<br/>Ransomware, botnets]

HA[Hacktivists<br/>Medium skill, political goals<br/>Protests, disruption]

IN[Insiders<br/>Varies, access & knowledge<br/>Revenge, profit]

SK[Script Kiddies<br/>Low skill, using tools<br/>Fame, curiosity]

end

NS -.->|Target| T1[Critical Infrastructure]

CC -.->|Target| T2[High-value IoT deployments]

HA -.->|Target| T3[Organizations, governments]

IN -.->|Target| T4[Own organization]

SK -.->|Target| T5[Random vulnerable devices]

style NS fill:#e74c3c,stroke:#c0392b,color:#fff

style CC fill:#E67E22,stroke:#d35400,color:#fff

style HA fill:#E67E22,stroke:#d35400,color:#fff

style IN fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style SK fill:#16A085,stroke:#0e6655,color:#fff

style T1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style T2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style T3 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style T4 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style T5 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

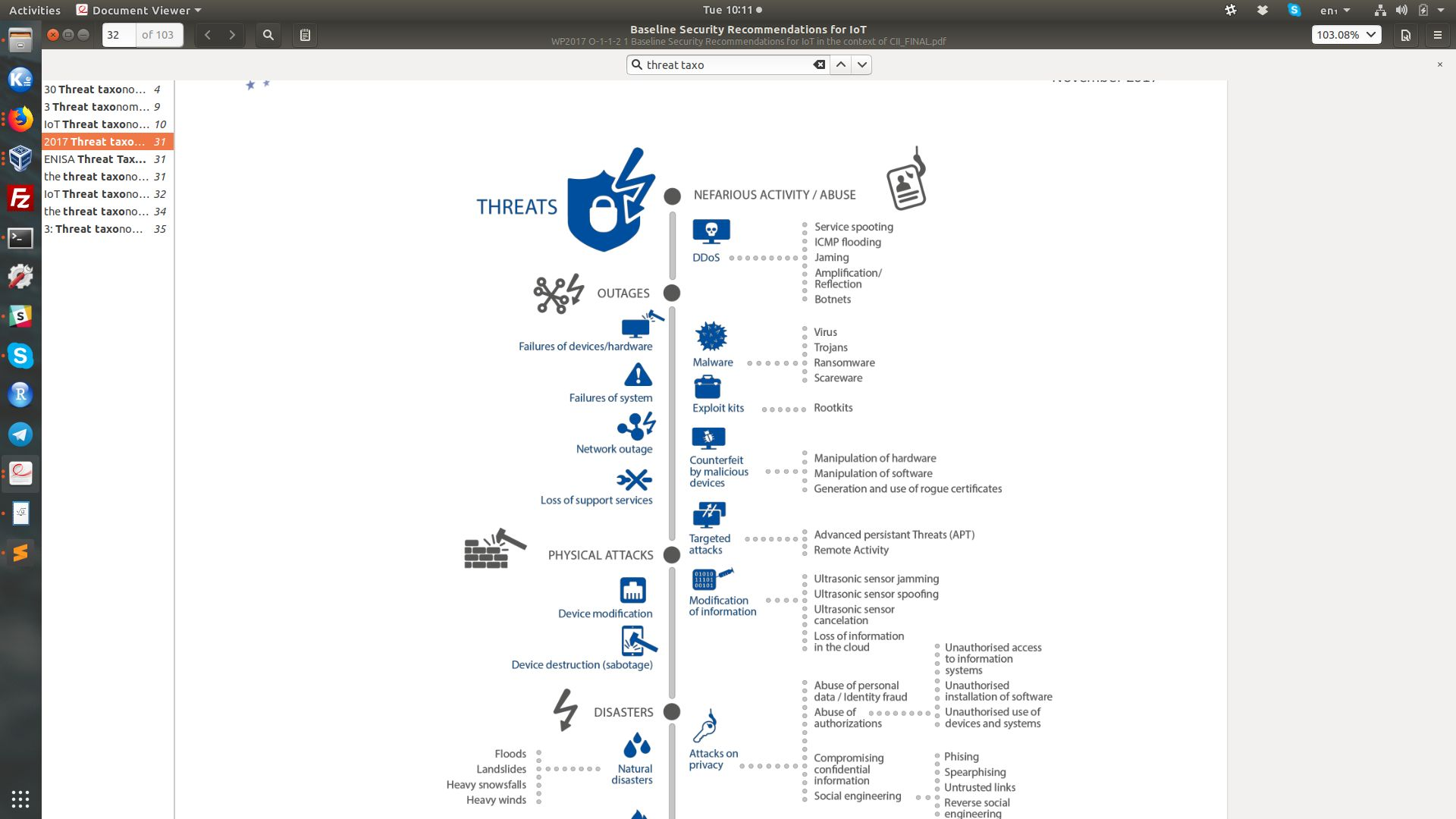

1401 Threat Landscape and STRIDE Model

1401.1 Threat Landscape Overview

Source: University of Edinburgh - IoT Security Course Materials

In 2014, security researchers discovered that a botnet of over 100,000 compromised IoT devices—including smart refrigerators—was being used to send out spam emails. The FTC launched their “Careful Connections” campaign warning consumers that “Smart devices can be dumb about security.”

Why this matters:

- Cyber-physical consequences: Unlike traditional computers, IoT attacks affect the physical world (unlock doors, disable cameras, control industrial machinery)

- Unpatchable devices: Many IoT devices can’t be updated, leaving vulnerabilities unfixed for their entire 10-20 year lifetime

- Fog computing for privacy: Processing data at the edge (fog layer) instead of sending everything to the cloud can protect user privacy while maintaining functionality

This case highlights three critical IoT security challenges we’ll explore: devices are vulnerable targets, attacks have physical consequences, and architectural choices (like fog computing) can mitigate both security and privacy risks.

Related: For privacy implications of IoT data collection, see Introduction to Privacy.

IoT systems face threats from various actors with different capabilities and motivations:

1401.1.1 Threat Actor Classification

| Actor Type | Skill Level | Motivation | Typical Targets | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Script Kiddies | Low | Fame, curiosity | Random devices | Mirai copycats |

| Cybercriminals | Medium-High | Financial gain | High-value targets | Ransomware, botnets |

| Hacktivists | Medium | Political/social | Organizations, governments | Anonymous, DDoS |

| Insiders | Varies | Revenge, profit | Own organization | Disgruntled employees |

| Nation States | Very High | Espionage, sabotage | Critical infrastructure | Stuxnet, APT groups |

| Competitors | Medium-High | Industrial espionage | Business rivals | IP theft |

Insiders are the most dangerous threat actors because they bypass perimeter security with legitimate credentials. In IoT systems, insiders can: - Extract device encryption keys during manufacturing - Plant backdoors in firmware before deployment - Disable security features with admin access - Exfiltrate sensitive sensor data over time

Mitigation: Implement zero-trust architecture (verify every action, even from insiders), separation of duties (no single person controls all security), audit logging (track all privileged actions), and background checks for personnel handling sensitive IoT infrastructure.

1401.1.2 Cyber Security 4-Quadrant Framework

Comprehensive IoT security requires protecting four interconnected domains:

| Quadrant | Security Concerns | IoT Examples | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| People | Insiders, attackers, social engineering | Disgruntled factory worker disables security cameras; phishing attack compromises admin credentials | Background checks, security training, zero-trust architecture, least privilege access |

| Processes | Purchasing, hiring, training, operations | Buying devices with known vulnerabilities; inadequate vetting of firmware developers | Vendor security requirements, secure SDLC, incident response plans, regular audits |

| Physical Environment | Data centers, communications, deployment | Accessible JTAG ports on deployed sensors; unencrypted Wi-Fi networks; unlocked server rooms | Tamper-evident seals, encrypted communications, locked cabinets, environmental monitoring |

| Technology | Hardware, applications, firmware, OS | Outdated OpenSSL library; buffer overflow in firmware; hardcoded credentials in device | Secure boot, code signing, vulnerability scanning, penetration testing, security patches |

Effective IoT security requires layering protections across all four quadrants:

- People: Train employees to recognize phishing + enforce multi-factor authentication

- Processes: Require security reviews in procurement + implement secure development lifecycle

- Physical: Lock network cabinets + use tamper-evident seals on devices

- Technology: Enable secure boot + encrypt data at rest and in transit

A weakness in one quadrant can compromise the entire system—attackers target the weakest link.

1401.2 STRIDE Threat Model for IoT

STRIDE is a threat modeling framework developed by Microsoft for systematically identifying security threats:

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#E67E22', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085', 'tertiaryColor': '#E67E22', 'fontSize': '13px'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph "STRIDE Threat Model"

S[Spoofing<br/>Impersonate identity<br/>Fake device/user]

T[Tampering<br/>Modify data/firmware<br/>MITM attacks]

R[Repudiation<br/>Deny actions<br/>No audit trail]

I[Information Disclosure<br/>Leak data<br/>Unauthorized access]

D[Denial of Service<br/>Make unavailable<br/>DDoS, battery drain]

E[Elevation of Privilege<br/>Gain unauthorized access<br/>Exploit vulnerabilities]

end

S -.->|Violates| A1[Authentication]

T -.->|Violates| A2[Integrity]

R -.->|Violates| A3[Non-repudiation]

I -.->|Violates| A4[Confidentiality]

D -.->|Violates| A5[Availability]

E -.->|Violates| A6[Authorization]

style S fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style T fill:#E67E22,stroke:#d35400,color:#fff

style R fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style I fill:#e74c3c,stroke:#c0392b,color:#fff

style D fill:#e74c3c,stroke:#c0392b,color:#fff

style E fill:#e74c3c,stroke:#c0392b,color:#fff

style A1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#0e6655,color:#fff

style A2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#0e6655,color:#fff

style A3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#0e6655,color:#fff

style A4 fill:#16A085,stroke:#0e6655,color:#fff

style A5 fill:#16A085,stroke:#0e6655,color:#fff

style A6 fill:#16A085,stroke:#0e6655,color:#fff

1401.2.1 Spoofing (Identity)

Definition: Pretending to be someone or something else

IoT Examples: - Fake sensor data injection - Rogue device joining network - MAC address spoofing - GPS spoofing for trackers

Attack Scenario:

// VULNERABLE: No device authentication

void processMessage(String message) {

// Blindly trust any message

float temperature = message.toFloat();

updateDatabase(temperature); // Could be fake data!

}

// SECURE: Verify sender identity

void processMessage(String message, String deviceId, String signature) {

if (!verifySignature(message, deviceId, signature)) {

Serial.println("ALERT: Invalid signature - potential spoofing!");

return;

}

float temperature = message.toFloat();

updateDatabase(temperature);

}Countermeasures: - Device certificates and mutual TLS - Message authentication codes (HMAC) - Challenge-response authentication

1401.2.2 Tampering (Data)

Definition: Unauthorized modification of data or code

IoT Examples: - Firmware modification - Sensor data manipulation - Configuration file changes - MITM attacks modifying packets

Attack Scenario:

# Attacker intercepts MQTT message

# Original: {"temperature": 22.5, "humidity": 60}

# Modified: {"temperature": 99.9, "humidity": 10}

# Result: Triggers false alarm, wrong decisions

# DEFENSE: Use digital signatures

import hashlib

import hmac

def sign_message(message, secret_key):

signature = hmac.new(

secret_key.encode(),

message.encode(),

hashlib.sha256

).hexdigest()

return f"{message}|{signature}"

def verify_message(signed_message, secret_key):

try:

message, signature = signed_message.split('|')

expected = hmac.new(

secret_key.encode(),

message.encode(),

hashlib.sha256

).hexdigest()

return hmac.compare_digest(signature, expected)

except:

return FalseCountermeasures: - Encryption (TLS/DTLS) - Digital signatures - Secure boot and verified firmware - Integrity checks (checksums, hashes)

1401.2.3 Repudiation (Non-repudiation)

Definition: Denying that an action occurred

IoT Examples: - User denies sending command - Device denies reporting data - No audit trail of changes

Attack Scenario:

User: "I never unlocked the door at 3 AM!"

System: [No logs to prove otherwise]

Malicious insider: "I didn't change the sensor calibration"

System: [No audit trail]Countermeasures:

// Implement comprehensive logging

#include <SD.h>

#include <TimeLib.h>

void logAction(String user, String action, String details) {

File logFile = SD.open("audit.log", FILE_APPEND);

String logEntry = String(now()) + "," +

user + "," +

action + "," +

details;

logFile.println(logEntry);

logFile.close();

// Also send to remote secure log server

sendToRemoteLog(logEntry);

}

// Usage

logAction("user@email.com", "DOOR_UNLOCK", "Front Door");Best Practices: - Immutable audit logs - Cryptographic timestamps - Remote log backup - Digital signatures on transactions

1401.2.4 Information Disclosure (Privacy)

Definition: Exposing information to unauthorized parties

IoT Examples: - Unencrypted sensor data transmission - Exposed API endpoints - Debug information leaking - Cloud storage misconfiguration

Attack Scenario:

# Attacker sniffs Wi-Fi traffic (unencrypted MQTT)

$ tcpdump -i wlan0 port 1883

# Captures: {"device": "bedroom_camera", "stream_url": "rtsp://..."}

# Result: Privacy invasion

# Attacker finds exposed API

$ curl http://iot-api.example.com/api/devices

# Returns: Complete list of all devices with credentials!Countermeasures:

// Always encrypt sensitive data

#include <WiFiClientSecure.h>

#include <PubSubClient.h>

WiFiClientSecure espClient;

PubSubClient mqtt(espClient);

void setup() {

// Use TLS certificate pinning

espClient.setCACert(ca_cert);

espClient.setCertificate(client_cert);

espClient.setPrivateKey(client_key);

// Connect to MQTTS (port 8883)

mqtt.setServer("broker.example.com", 8883);

}

// Sanitize debug output

void debugPrint(String message) {

#ifdef DEBUG

// Never log sensitive data

message.replace(password, "***REDACTED***");

Serial.println(message);

#endif

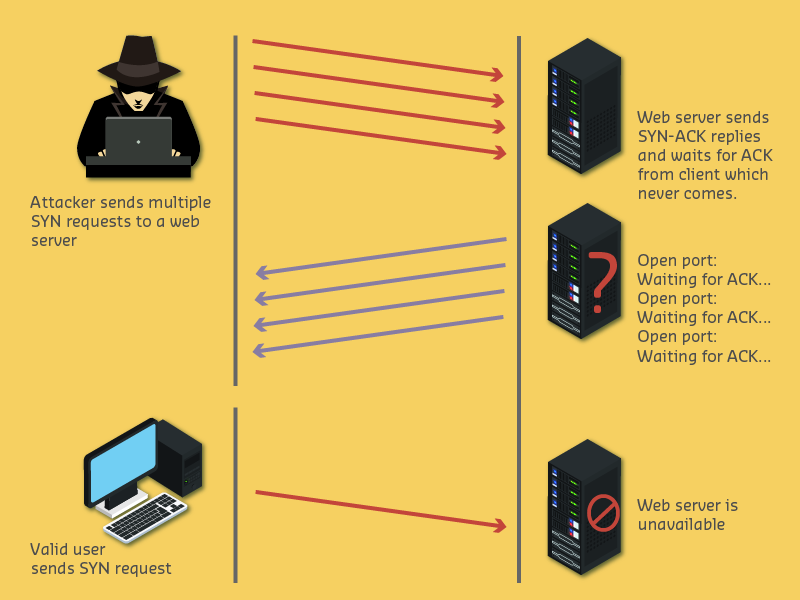

}1401.2.5 Denial of Service (Availability)

Definition: Making system unavailable to legitimate users

IoT Examples: - DDoS attacks (Mirai botnet) - Battery depletion attacks - Network flooding - Resource exhaustion

Attack Scenarios:

// Scenario 1: Battery depletion attack

// Attacker sends continuous ping requests

// Device stays awake responding - battery drains

// DEFENSE: Rate limiting

unsigned long lastResponse = 0;

const int MIN_RESPONSE_INTERVAL = 5000; // 5 seconds

void handlePing() {

if (millis() - lastResponse < MIN_RESPONSE_INTERVAL) {

// Drop request - too frequent

return;

}

lastResponse = millis();

sendPingResponse();

}Countermeasures: - Rate limiting and throttling - Input validation - Resource quotas - DDoS mitigation services (Cloudflare) - Watchdog timers

1401.2.6 Elevation of Privilege (Authorization)

Definition: Gaining unauthorized access or permissions

IoT Examples: - Buffer overflow to gain root - SQL injection to admin account - Exploiting debug interfaces - Firmware backdoors

Attack Scenario:

// VULNERABLE: Buffer overflow

void handle_command(char *input) {

char buffer[64];

strcpy(buffer, input); // No bounds checking!

// Attacker sends 200 bytes -> buffer overflow

// -> Overwrites return address -> Executes malicious code

}

// SECURE: Bounds checking

void handle_command(char *input) {

char buffer[64];

strncpy(buffer, input, sizeof(buffer) - 1);

buffer[sizeof(buffer) - 1] = '\0';

}Countermeasures: - Least privilege principle - Input validation and sanitization - Memory-safe programming - Disable debug interfaces in production - Role-based access control (RBAC)

1401.3 Common Security Pitfalls

The Mistake: Organizations assume IoT devices are protected because they are “behind the firewall” or on a “private network.” Security controls are applied only at the network edge, leaving internal IoT traffic unencrypted and unauthenticated.

Why It Happens: Traditional IT security focused on perimeter defense (castle-and-moat model). IoT devices have limited resources, so encryption seems expensive. Internal networks are assumed trustworthy. VLANs provide network isolation, creating false confidence.

The Fix: Implement defense-in-depth with zero-trust principles: - Encrypt all traffic: Use TLS/DTLS even on internal networks. Assume attackers are already inside (lateral movement). - Authenticate every device: Use X.509 certificates or pre-shared keys for device-to-device and device-to-gateway communication. - Network segmentation: Isolate IoT devices on dedicated VLANs with strict firewall rules. Block IoT-to-IoT communication unless explicitly required. - Microsegmentation: Apply per-device or per-application firewall policies. A compromised thermostat should not reach the financial database. - Monitor east-west traffic: Deploy network detection tools (Zeek, Suricata) to detect anomalous internal communication patterns.

The Mistake: API keys, Wi-Fi passwords, MQTT broker credentials, or cloud service tokens are hardcoded directly in device firmware or checked into version control.

Why It Happens: Hardcoding works during development and prototyping. Developers forget to remove credentials before committing. Configuration management for IoT fleets is complex.

The Fix: Implement proper credential management: - Never hardcode: Use environment variables, secure element storage, or runtime provisioning. Treat any credential in source code as compromised. - Manufacturing provisioning: Inject unique credentials per device during manufacturing using secure provisioning stations. - Runtime provisioning: Use device provisioning protocols (AWS IoT Just-in-Time Provisioning, Azure DPS) to issue unique certificates on first boot. - Secret scanning: Add pre-commit hooks with tools like trufflehog, git-secrets, or detect-secrets to prevent credential commits.

1401.4 What’s Next

Now that you understand the STRIDE threat model and threat landscape, continue to:

- OWASP IoT Top 10 Vulnerabilities - Explore the most critical IoT security vulnerabilities

- Security Compliance Frameworks - Understand NIST, ETSI, IEC 62443, and FDA security standards

- Interactive Security Tools - Use risk calculators and attack surface visualizers