%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

A["ROOT A<br/>Rank: 0<br/>Routing Table:<br/>B→B, C→B, D→C<br/>E→B, F→B"]

B["Node B<br/>Rank: 100<br/>Routing Table:<br/>E→E, F→F"]

C["Node C<br/>Rank: 100<br/>Routing Table:<br/>D→D"]

D["Node D<br/>Rank: 200"]

E["Node E<br/>Rank: 200"]

F["Node F<br/>Rank: 200"]

A --> B

A --> C

B --> E

B --> F

C --> D

style A fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff,stroke-width:3px

style B fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style C fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style D fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style E fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style F fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

709 RPL Routing Modes and Traffic Patterns

709.1 RPL Routing Modes

RPL supports two modes with different memory/performance trade-offs:

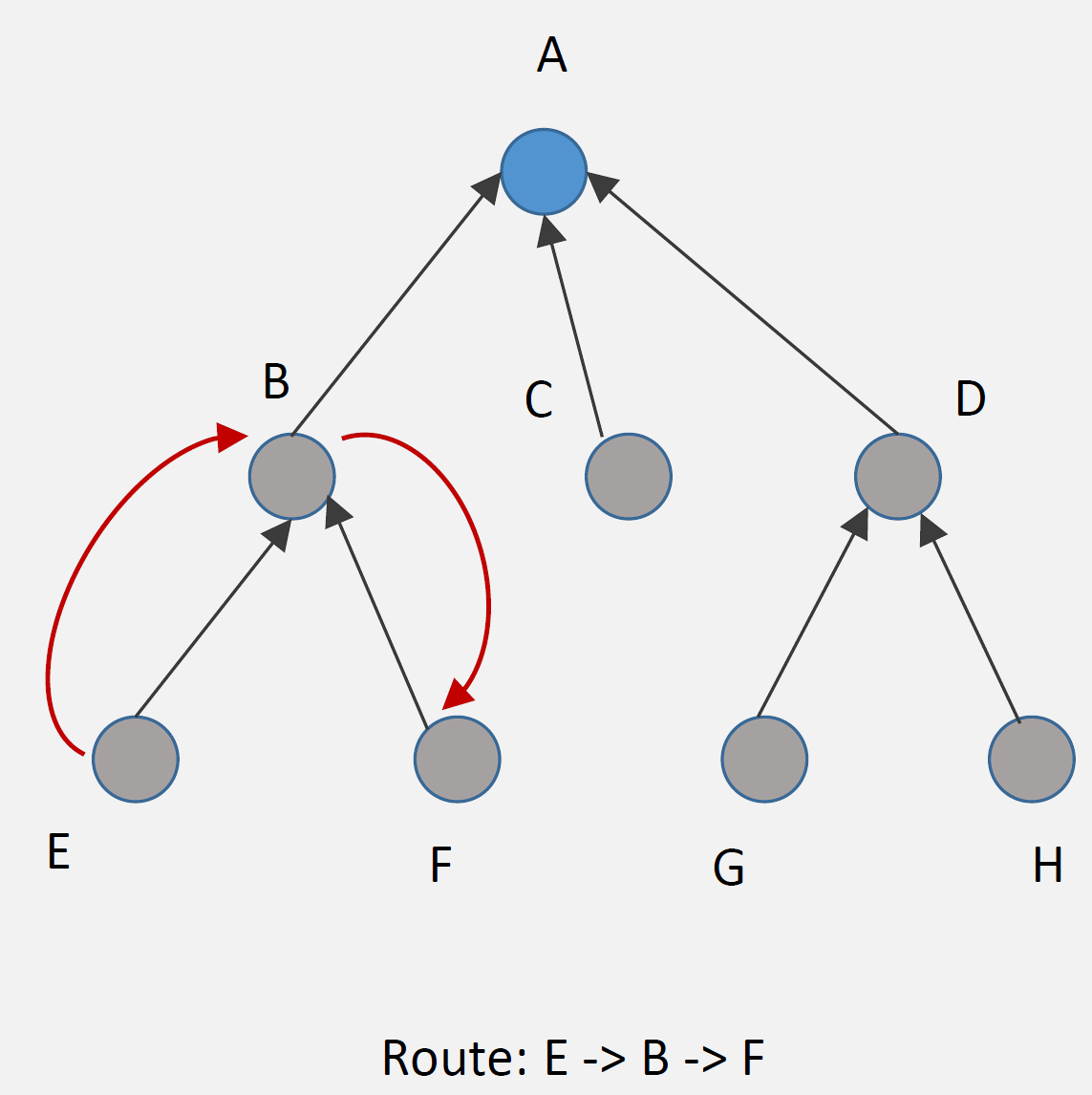

709.1.1 Storing Mode

Each node maintains routing table for its sub-DODAG.

{fig-alt=“RPL Storing mode showing distributed routing tables: ROOT maintains routes to all nodes, intermediate nodes B and C maintain routes to their descendants, enabling distributed forwarding decisions”}

How It Works: 1. DAO messages: Nodes advertise reachability to parents 2. Routing tables: Each node stores routes to descendants 3. Packet forwarding: Node looks up destination in table, forwards to appropriate child

Example Route (E → F):

Step 1: E sends packet to parent B (upward)

Step 2: B checks routing table: "F is my child"

Step 3: B forwards directly to F (downward)

Route: E → B → F (optimal)Advantages: - Efficient routing: Optimal paths (no detour through root) - Low latency: Direct routes between any nodes - Root not bottleneck: Distributed routing decisions

Disadvantages: - Memory overhead: Each node stores routing table - Scalability: Routing tables grow with network size - Updates: DAO messages for every node change

Best For: - Devices with sufficient memory (32+ KB RAM) - Networks requiring low latency - Point-to-point communication common

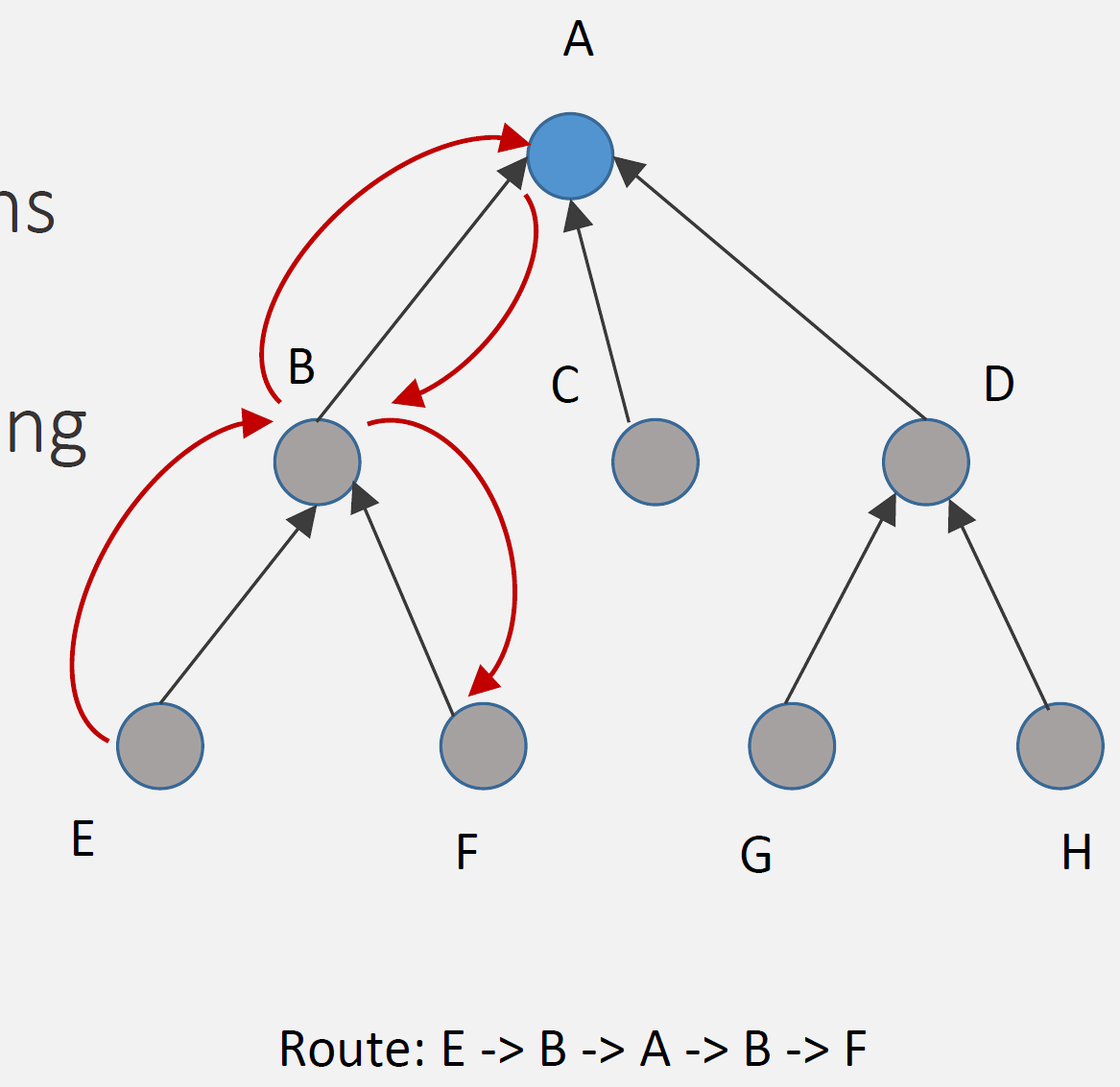

709.1.2 Non-Storing Mode

Only root maintains routing information; exploits source routing.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

A["ROOT A<br/>Rank: 0<br/>Routing Table:<br/>B→B, C→C, D→C,D<br/>E→B,E, F→B,F<br/>(Complete topology)"]

B["Node B<br/>Rank: 100<br/>Parent pointer only<br/>(No routing table)"]

C["Node C<br/>Rank: 100<br/>Parent pointer only<br/>(No routing table)"]

D["Node D<br/>Rank: 200<br/>Parent: C"]

E["Node E<br/>Rank: 200<br/>Parent: B"]

F["Node F<br/>Rank: 200<br/>Parent: B"]

A --> B

A --> C

B --> E

B --> F

C --> D

style A fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff,stroke-width:3px

style B fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style C fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style D fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style E fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style F fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

{fig-alt=“RPL Non-Storing mode showing centralized routing at ROOT with complete topology, intermediate nodes maintain only parent pointers, downward routing uses source routing headers from root”}

How It Works: 1. DAO to root: All nodes send DAO directly to root (upward) 2. Root stores all routes: Only root has complete routing table 3. Source routing: Root inserts complete path in packet header 4. Nodes forward: Follow instructions in packet header (no table lookup)

Example Route (E → F):

Step 1: E sends packet to parent B (upward, default route)

Step 2: B forwards to parent A (root) (upward, default route)

Step 3: A (root) checks routing table: "F via B"

Step 4: A inserts source route: [B, F]

Step 5: A sends to B with route in header

Step 6: B forwards to F following route

Route: E → B → A → B → F (via root)Advantages: - Low memory: Nodes don’t store routing tables (just parent) - Simple nodes: Minimal routing logic - Scalability: Network size doesn’t affect node memory

Disadvantages: - Suboptimal routes: All point-to-point traffic via root - Higher latency: Extra hops through root - Root bottleneck: All routing decisions at root - Header overhead: Source route in every packet

Best For: - Resource-constrained devices (< 16 KB RAM) - Primarily many-to-one traffic (sensors → gateway) - Point-to-point communication rare - Large networks (many nodes)

709.1.3 Storing vs Non-Storing Comparison

| Aspect | Storing Mode | Non-Storing Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Routing Table | Distributed (all nodes) | Centralized (root only) |

| Node Memory | Higher (routing table) | Lower (parent pointer only) |

| Route Optimality | Optimal (direct paths) | Suboptimal (via root) |

| Latency | Lower | Higher (extra hops) |

| Root Load | Low | High (all routing decisions) |

| Scalability | Limited by node memory | Limited by root capacity |

| DAO Destination | Parent | Root (through parents) |

| Header Overhead | Low | High (source routing) |

| Best For | Powerful nodes, low latency | Constrained nodes, many-to-one |

This variant provides a practical decision guide for choosing between Storing and Non-Storing modes based on your network characteristics.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#E67E22', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085', 'tertiaryColor': '#E8F6F3', 'fontSize': '10px'}}}%%

flowchart TD

START["RPL Mode<br/>Selection"] --> Q1{"Primary traffic<br/>pattern?"}

Q1 -->|"Many-to-One<br/>(sensors→gateway)"| Q2{"Node memory<br/>available?"}

Q1 -->|"Point-to-Point<br/>(device↔device)"| Q3{"Latency<br/>requirement?"}

Q2 -->|"< 64KB RAM"| NS1["NON-STORING<br/>━━━━━━━━━━<br/>Memory efficient<br/>Root handles routing<br/>Best: Sensor networks"]

Q2 -->|"> 64KB RAM"| Q4{"Network size?"}

Q3 -->|"< 100ms"| ST1["STORING<br/>━━━━━━━━━━<br/>Direct P2P routes<br/>Lower latency<br/>Best: Industrial control"]

Q3 -->|"> 100ms OK"| NS2["NON-STORING"]

Q4 -->|"< 200 nodes"| ST2["STORING<br/>━━━━━━━━━━<br/>Optimal paths<br/>Distributed load<br/>Best: Building automation"]

Q4 -->|"> 200 nodes"| NS3["NON-STORING<br/>━━━━━━━━━━<br/>Scales better<br/>Root manages all"]

style START fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style Q1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Q2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Q3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Q4 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style NS1 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style NS2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style NS3 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style ST1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style ST2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

Key Insight: Non-Storing mode is the default choice for resource-constrained sensor networks. Only move to Storing mode when you have both the memory budget AND specific P2P or latency requirements.

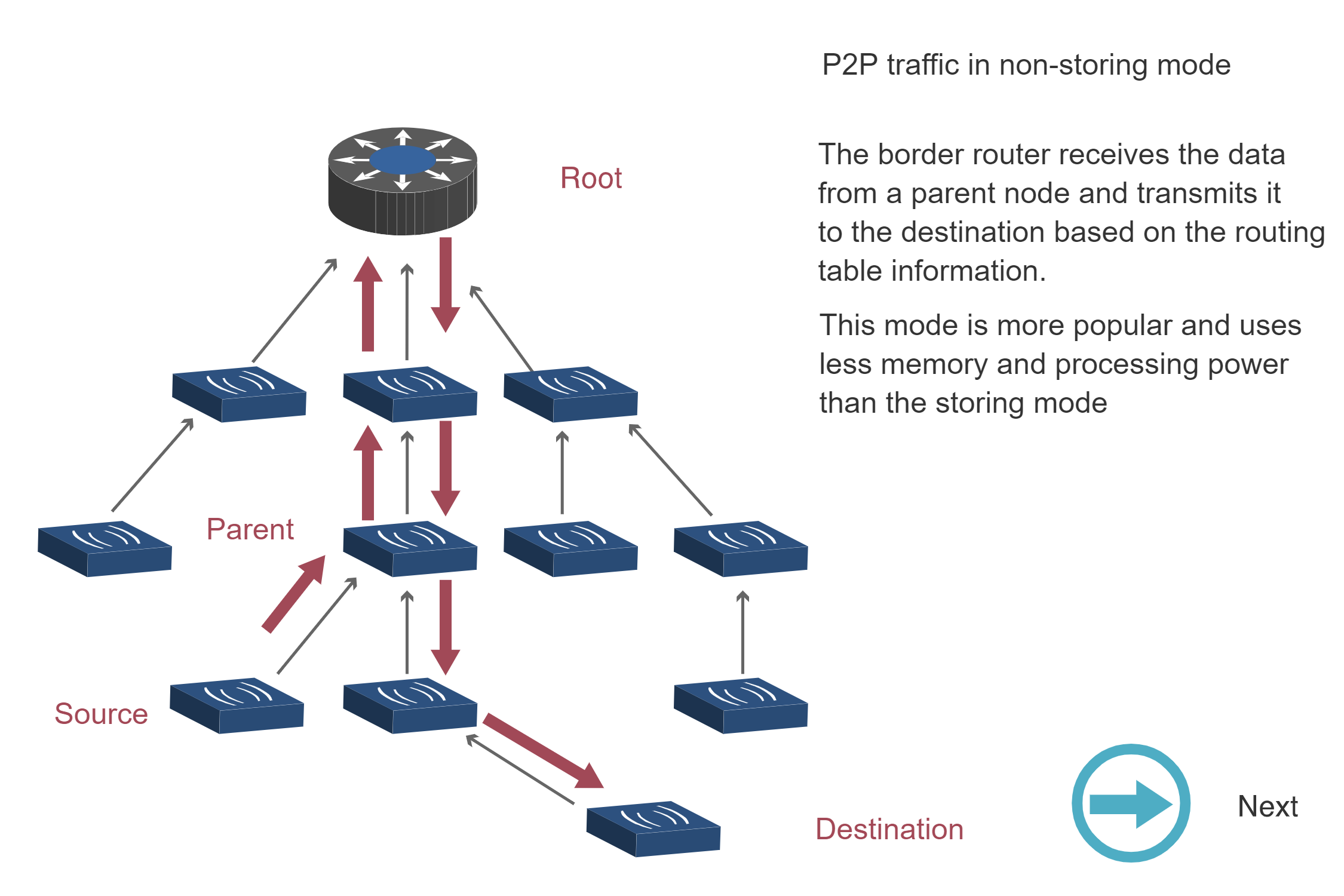

The following sequence diagrams illustrate how RPL handles point-to-point (P2P) traffic in Non-Storing and Storing modes.

Non-Storing Mode P2P Traffic (Steps 1-3):

Storing Mode P2P Traffic:

Key Insight: Non-Storing mode requires all P2P traffic to traverse the root (3 diagrams showing upward then downward path), while Storing mode enables direct routing through the nearest common ancestor (1 diagram showing optimized path). This explains why Storing mode has lower latency for P2P traffic despite higher memory requirements.

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 4 - Routing

709.2 RPL Traffic Patterns

RPL optimizes for different traffic directions:

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph ManyToOne["Many-to-One<br/>(Upward)"]

S1["Sensor 1"] --> GW1["Gateway"]

S2["Sensor 2"] --> GW1

S3["Sensor 3"] --> GW1

S4["Sensor 4"] --> GW1

end

subgraph OneToMany["One-to-Many<br/>(Downward)"]

GW2["Gateway"] --> A1["Actuator 1"]

GW2 --> A2["Actuator 2"]

GW2 --> A3["Actuator 3"]

end

subgraph P2P["Point-to-Point"]

SEN["Sensor"] --> ACT["Actuator"]

end

style ManyToOne fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style OneToMany fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style P2P fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style GW1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style GW2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S1 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style S2 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style S3 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style S4 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style A1 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style A2 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style A3 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style SEN fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#7F8C8D,color:#2C3E50

style ACT fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#7F8C8D,color:#2C3E50

{fig-alt=“RPL traffic patterns: Many-to-One shows multiple sensors sending to gateway (upward routing), One-to-Many shows gateway sending to multiple actuators (downward), Point-to-Point shows direct sensor to actuator communication”}

709.2.1 Many-to-One (Upward Routing)

Pattern: Many sensors → Single gateway/root

How: - Each node knows parent (from DODAG construction) - Default route: Send to parent (toward root) - No routing table needed (upward)

Example: Temperature sensors reporting to cloud

Sensor 3 → Node 1 → Root → Internet → Cloud

(Upward along DODAG tree)Optimization: - Most common traffic in IoT (data collection) - Minimal state: Just parent pointer - Efficient: Direct path to root

709.2.2 One-to-Many (Downward Routing)

Pattern: Single controller → Many actuators

How: - Storing mode: Each node has routing table, forwards optimally - Non-storing mode: Root inserts source route, nodes follow

Example: Controller sends “turn off” to all lights

Root → [Multicast or unicast to each light]Modes: - Storing: Root → Node 1 → Light 3 (optimal) - Non-storing: Root inserts route [Node 1, Light 3]

709.2.3 Point-to-Point (P2P)

Pattern: Sensor ↔︎ Actuator (peer-to-peer)

How: - Upward then downward (via common ancestor, often root) - Storing mode: May find shorter path - Non-storing mode: Always via root

Example: Motion sensor triggers light

Storing: Sensor 3 → Node 1 → Light 4 (3 hops, if both under Node 1)

Non-Storing: Sensor 3 → Node 1 → Root → Node 2 → Light 4 (4 hops)