%% fig-alt: "Timeline view showing data journey through network layers: starting from Application layer where user data is created, traveling down through Transport (adding port numbers), Network (adding IP addresses), Data Link (adding MAC addresses), to Physical layer (converting to signals), then across the network medium, and back up the layers on the receiving device with headers stripped at each level"

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#E67E22', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#2C3E50', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085', 'tertiaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'fontSize': '13px'}}}%%

sequenceDiagram

participant App as Application<br/>User Data

participant Trans as Transport<br/>+ Ports

participant Net as Network<br/>+ IP Addr

participant Link as Data Link<br/>+ MAC Addr

participant Phys as Physical<br/>Signals

participant Wire as Network Medium

participant RPhys as Physical<br/>Receive

participant RLink as Data Link<br/>Strip MAC

participant RNet as Network<br/>Strip IP

participant RTrans as Transport<br/>Strip Port

participant RApp as Application<br/>Deliver

Note over App,Phys: SENDER: Encapsulation (headers added)

App->>Trans: "Hello" + MQTT header

Trans->>Net: Segment + TCP port 1883

Net->>Link: Packet + IP 192.168.1.10

Link->>Phys: Frame + MAC aa:bb:cc:dd:ee:ff

Phys->>Wire: Radio/electrical signals

Note over Wire: Transmission across medium

Note over RPhys,RApp: RECEIVER: Decapsulation (headers removed)

Wire->>RPhys: Receive signals

RPhys->>RLink: Reconstruct frame

RLink->>RNet: Extract packet (MAC validated)

RNet->>RTrans: Extract segment (IP matched)

RTrans->>RApp: Deliver "Hello" to app

650 Encapsulation and Protocol Data Units

650.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain encapsulation: Describe how headers are added as data moves down the protocol stack

- Explain decapsulation: Describe how headers are removed as data moves up the stack

- Name Protocol Data Units (PDUs): Identify the correct PDU name at each layer (Data, Segment, Packet, Frame, Bits)

- Analyze packet overhead: Calculate the byte overhead added by protocol headers

- Trace data flow: Follow an IoT message from application to physical transmission and back

Core concept: Encapsulation is like putting a letter in envelopes - each layer adds its own “envelope” (header) around the data from the layer above. At the destination, each layer removes its envelope and passes the contents up.

Why it matters: Understanding encapsulation explains why small IoT messages become much larger on the wire (header overhead), why protocols like 6LoWPAN compress headers, and how to interpret packet captures in Wireshark.

Key takeaway: Data becomes Segment (Transport) becomes Packet (Network) becomes Frame (Data Link) becomes Bits (Physical). Each transformation adds addressing and control information.

650.2 Prerequisites

- OSI and TCP/IP Models: Understanding of the layered network model structure

Just like a letter gets wrapped:

- Letter (your message) goes in an…

- Envelope (with sender/receiver address) goes in a…

- Mail bag (sorted by region) loaded on a…

- Truck/plane (physical transport)

Each layer adds its “envelope” (header) around the data from the layer above.

At the destination, each layer removes its envelope and passes the contents up.

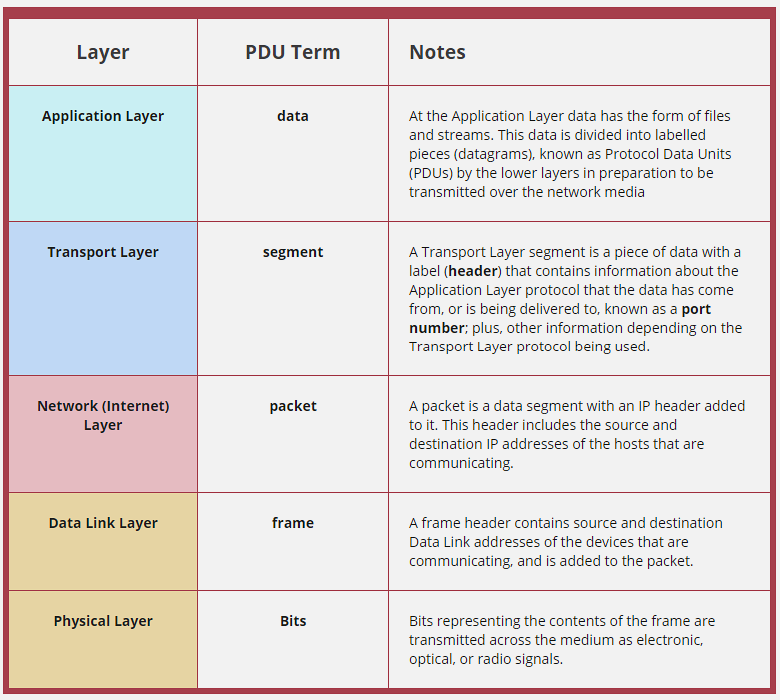

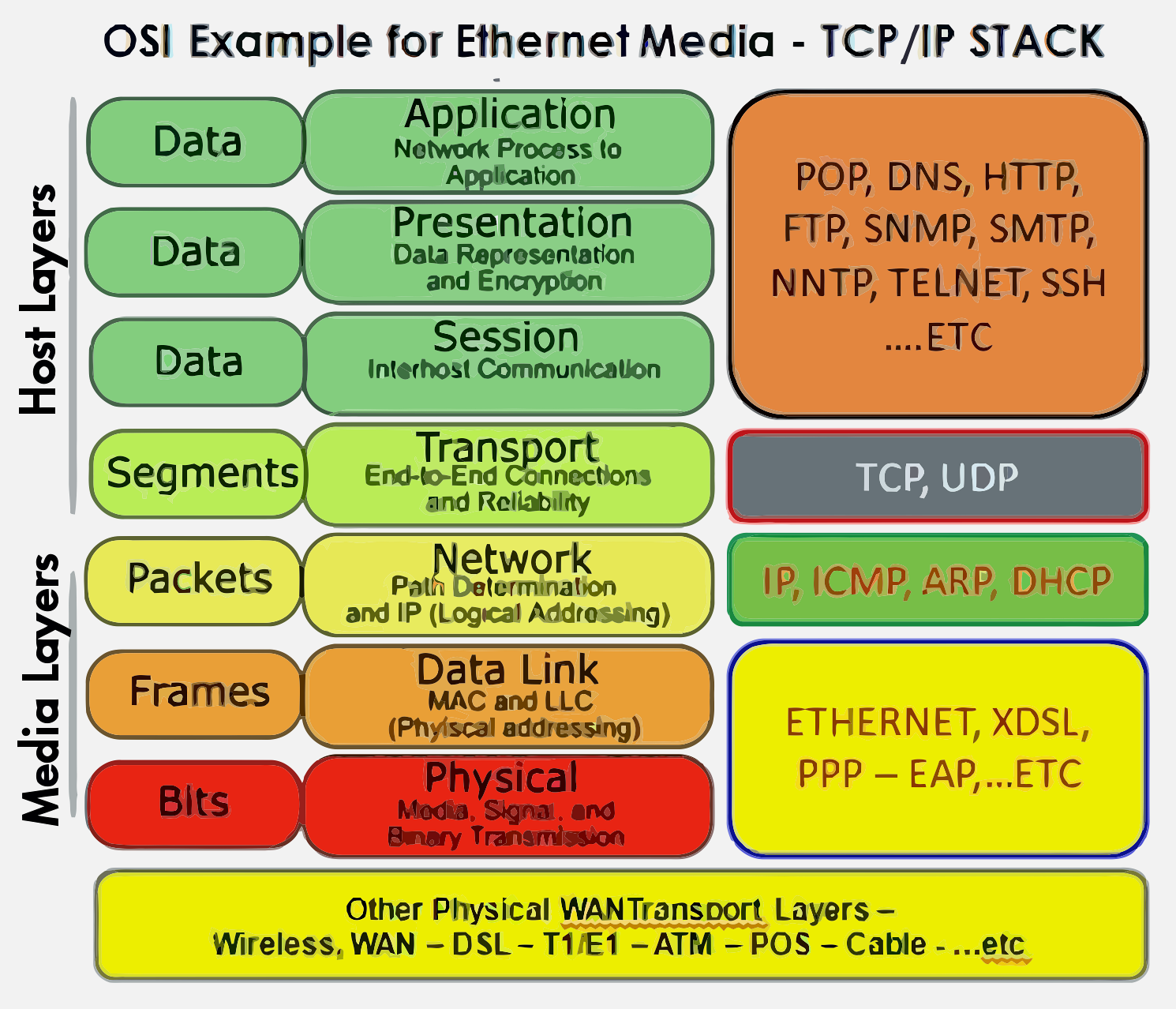

650.3 Protocol Data Units (PDUs)

650.3.1 Data at Each Layer

As data moves through the protocol stack, it gets different names and structures at each layer.

650.3.2 PDU Names by Layer

| Layer | PDU Name | Contains |

|---|---|---|

| Application | Data | Raw application data (email, file, sensor reading) |

| Transport | Segment (TCP) or Datagram (UDP) | Data + port numbers + sequence info |

| Internet | Packet | Segment + source/destination IP addresses |

| Network Access | Frame | Packet + source/destination MAC addresses |

| Physical | Bits | Electronic, radio, or optical signals |

650.4 How Data Moves Through Layers

When you send “Hello!” to a smart device:

SENDING (Your Phone) RECEIVING (Smart Device)

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

APP: "Hello!" APP: "Hello!" ✓

↓ add MQTT header ↑ remove MQTT

TRANS: [TCP][Hello!] TRANS: [TCP][Hello!]

↓ add IP header ↑ remove IP

NET: [IP][TCP][Hello!] NET: [IP][TCP][Hello!]

↓ add Wi-Fi header ↑ remove Wi-Fi

LINK: [Wi-Fi][IP][TCP][Hello!] LINK: [Wi-Fi][IP][TCP][Hello!]

↓ ↑

PHYS: ~~~radio waves~~~ →→→ PHYS: ~~~radio waves~~~Key insight: Each layer adds its own “envelope” (header) going down, and removes it going up. This is called encapsulation.

650.5 IoT Example: Temperature Sensor

Your temperature sensor sends “72F” to the cloud:

| Layer | What Happens | Protocol Used |

|---|---|---|

| Application | Format: {"temp": 72} |

MQTT |

| Transport | Add sequence number, port | UDP |

| Network | Add IP addresses | 6LoWPAN (compressed IPv6) |

| Data Link | Add device addresses | Zigbee MAC |

| Physical | Convert to radio signal | 2.4 GHz radio |

Total journey: 5 layers down at sensor - over the air - 5 layers up at gateway - internet - cloud!

Application Layer Data:

{

"sensor_id": "TEMP-001",

"temperature": 22.5,

"humidity": 45.0,

"timestamp": "2025-10-25T10:30:00Z"

}After each layer adds headers: 1. Segment: + TCP port 8883 (MQTT), sequence number 2. Packet: + IP addresses (192.168.1.100 -> 203.0.113.42) 3. Frame: + MAC addresses (sensor MAC -> gateway MAC) 4. Bits: Transmitted as Wi-Fi radio signals

650.6 Encapsulation and Decapsulation

650.6.1 The Process

Encapsulation: Headers (and trailers) are progressively ADDED as data moves DOWN the layers.

Decapsulation: Headers (and trailers) are progressively REMOVED as data moves UP the layers.

650.6.2 Email Example: The Jacket Analogy

Sending an email - data moves through layers like putting on jackets:

Think of it like: - Each layer puts a “jacket” on the data (with zippers/buttons = protocol rules) - The equivalent layer at the destination knows how to remove that jacket - Only layers at the same level understand each other’s jackets

Headers contain control and management information: - Addressing (where to send) - Sequencing (order of packets) - Error checking (data integrity) - Protocol identification (what’s inside)

650.7 Byte-Level Analysis: Understanding Overhead

650.7.1 Detailed Frame Structure

%% fig-alt: "Detailed byte-level breakdown of a network frame showing actual header sizes: Ethernet header 14 bytes (6 dest MAC + 6 src MAC + 2 type), IP header 20 bytes minimum, TCP header 20 bytes minimum, and application payload, with total overhead calculation showing that a 50-byte payload becomes 104 bytes on the wire"

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#E67E22', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#2C3E50', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085', 'tertiaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'fontSize': '11px'}}}%%

flowchart LR

subgraph Frame["Complete Ethernet Frame (minimum 64 bytes)"]

direction LR

subgraph EthHdr["Ethernet Header: 14 bytes"]

DestMAC["Dest MAC<br/>6 bytes"]

SrcMAC["Src MAC<br/>6 bytes"]

EthType["Type<br/>2 bytes"]

end

subgraph IPHdr["IP Header: 20 bytes min"]

IPVer["Ver+IHL<br/>1 byte"]

IPTOS["ToS<br/>1 byte"]

IPLen["Length<br/>2 bytes"]

IPId["ID<br/>2 bytes"]

IPFlags["Flags<br/>2 bytes"]

IPTTL["TTL<br/>1 byte"]

IPProto["Proto<br/>1 byte"]

IPChk["Checksum<br/>2 bytes"]

IPSrc["Src IP<br/>4 bytes"]

IPDst["Dst IP<br/>4 bytes"]

end

subgraph TCPHdr["TCP Header: 20 bytes min"]

TCPSrc["Src Port<br/>2 bytes"]

TCPDst["Dst Port<br/>2 bytes"]

TCPSeq["Seq Num<br/>4 bytes"]

TCPAck["Ack Num<br/>4 bytes"]

TCPFlags["Flags<br/>2 bytes"]

TCPWin["Window<br/>2 bytes"]

TCPChk["Checksum<br/>2 bytes"]

TCPUrg["Urgent<br/>2 bytes"]

end

Payload["App Data<br/>Variable"]

FCS["FCS<br/>4 bytes"]

end

subgraph Summary["Overhead Analysis"]

Calc["50-byte payload<br/>+ 14 (Eth) + 20 (IP)<br/>+ 20 (TCP) + 4 (FCS)<br/>= 108 bytes total<br/><b>54% overhead!</b>"]

end

style DestMAC fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style SrcMAC fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style EthType fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPVer fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPTOS fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPLen fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPId fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPFlags fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPTTL fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPProto fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPChk fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPSrc fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IPDst fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style TCPSrc fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style TCPDst fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style TCPSeq fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style TCPAck fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style TCPFlags fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style TCPWin fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style TCPChk fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style TCPUrg fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Payload fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style FCS fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Calc fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

650.7.2 Header Overhead Calculation

| Component | Size | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Ethernet Header | 14 bytes | Dest MAC (6) + Src MAC (6) + Type (2) |

| IP Header | 20 bytes min | Version, length, TTL, addresses, etc. |

| TCP Header | 20 bytes min | Ports, sequence numbers, flags, etc. |

| Frame Check Sequence | 4 bytes | Error detection |

| Total Overhead | 58 bytes | Before any payload! |

For IoT implications: - A 10-byte sensor reading becomes 68+ bytes on the wire - That’s 85% overhead for small payloads! - This is why IoT protocols like 6LoWPAN compress IPv6 headers from 40 bytes down to 2-6 bytes

650.8 Visual Reference Gallery

650.8.1 Protocol Data Units

650.9 Summary

This chapter covered how data is transformed as it moves through the protocol stack:

- Encapsulation adds headers progressively as data moves DOWN the stack (Data to Segment to Packet to Frame to Bits), with each layer wrapping the previous layer’s output

- Decapsulation removes headers progressively as data moves UP the stack, with each layer stripping its header and passing contents to the layer above

- Protocol Data Units (PDUs) have specific names: Application data becomes Transport segment/datagram, then Network packet, then Data Link frame, finally Physical bits

- Header overhead is significant: Standard TCP/IP adds 54+ bytes to every message, which is why IoT uses header compression techniques like 6LoWPAN

- Each header contains control information: addressing (where to send), sequencing (packet order), error checking (integrity), and protocol identification (what’s inside)

650.10 What’s Next

Continue your exploration of layered network models:

- IoT Reference Models: Explore IoT-specific architectures including the ITU model and Cisco 7-Level reference model

- Layered Models: Labs and Implementation: Hands-on MAC/IP addressing, ARP, and Python implementations

- Layered Models: Review: Test your understanding with comprehensive knowledge checks