%% fig-alt: "Ethernet frame field structure showing header components including destination MAC, source MAC, type, payload, and FCS"

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#E67E22', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#2C3E50', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085', 'tertiaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'fontSize': '13px'}}}%%

graph LR

Preamble["Preamble<br/>8 bytes<br/>Sync pattern"]

DestMAC["Dest MAC<br/>6 bytes<br/>Target device"]

SrcMAC["Source MAC<br/>6 bytes<br/>Sender device"]

Type["Type/Length<br/>2 bytes<br/>Protocol (0x0800=IP)"]

Payload["Payload<br/>46-1500 bytes<br/>IP packet"]

FCS["FCS<br/>4 bytes<br/>Error check"]

Preamble --> DestMAC --> SrcMAC --> Type --> Payload --> FCS

style Preamble fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style DestMAC fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style SrcMAC fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Type fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Payload fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style FCS fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

652 Layered Models: Labs and Implementation

652.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Work with MAC Addresses: Read, interpret, and configure hardware addresses on IoT devices

- Implement Layer 2 Communication: Use Ethernet and Wi-Fi protocols for local network communication

- Analyze Network Frames: Capture and dissect data link layer frames using packet analyzers

- Configure ARP: Understand Address Resolution Protocol for IP-to-MAC mapping

- Design Local Networks: Plan L2 topologies for IoT deployments with switches and access points

- Troubleshoot Connectivity: Diagnose MAC-level issues including duplicate addresses and broadcast storms

652.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

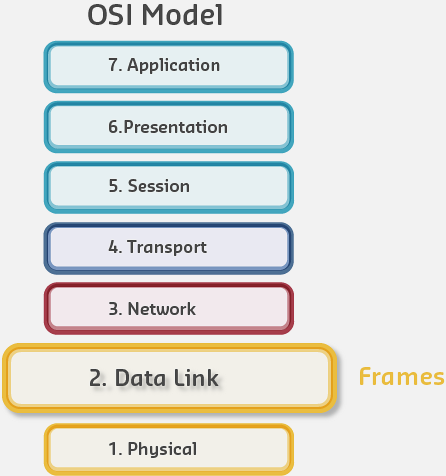

- Layered Models: Fundamentals: Understanding of the OSI and TCP/IP layered models is essential for grasping how Layer 2 (Data Link) and Layer 3 (Network) work together through encapsulation

- Networking Basics for IoT: Basic networking concepts including network topologies, addressing schemes, and protocol fundamentals provide context for MAC and IP addressing

- Binary and hexadecimal arithmetic: MAC addresses are 48-bit values represented in hexadecimal, and subnet calculations require binary operations, so comfort with these number systems is important

- Command-line basics: Labs use terminal commands (ipconfig, arp, ifconfig) to explore network configuration, so familiarity with command-line interfaces is helpful

652.3 🌱 Getting Started (For Beginners)

The fundamentals chapter introduced layered models in theory. This chapter shows you what those layers look like on real devices.

- As you run the labs (

ipconfig,arp, packet captures), always ask:- Which layer am I looking at right now? (MAC, IP, TCP/UDP, application)

- How does this field relate to the diagrams in

layered-models-fundamentals.qmd?

- If you cannot run the commands:

- Study the sample outputs and highlight which parts are Layer 2 (MAC) vs Layer 3 (IP).

Helpful mapping while you work:

| Layer | Examples in this chapter |

|---|---|

| L2 | MAC addresses, Ethernet frames, ARP table |

| L3 | IPv4 addresses, subnet masks, routing entries |

| L4 | TCP/UDP ports shown in packet captures |

If layer boundaries still feel abstract, revisit layered-models-fundamentals.qmd and then use these labs as a “field guide” that ties the conceptual stack to actual commands and packet traces.

Fundamentals: - Layered Models Fundamentals - OSI/TCP-IP model theory - Layered Network Models - Complete layered model exploration - Networking Basics - Network fundamentals and topologies

Addressing: - Addressing and Subnetting - IP addressing and subnet design - Network Access and Physical - Physical layer protocols

Implementation: - Networking Labs - Additional hands-on exercises - Wired Communication - UART, I2C, SPI protocols

Review: - Layered Models Review - Assessment and comprehensive quiz

Learning: - Simulations Hub - Network protocol simulators and tools

652.4 Data Link Layer: MAC Addressing

652.4.1 What is a MAC Address?

MAC (Media Access Control) address is the hardware address assigned to network interface controllers.

Purpose: Send and receive data frames at the Data Link layer (OSI Layer 2)

Used by: - Ethernet (IEEE 802.3) - Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11) - Bluetooth (IEEE 802.15.1) - Most IEEE 802 standard technologies

652.4.2 Ethernet Frame Structure

Frame header contains: - Destination MAC address: Where is this frame going? - Source MAC address: Where did this frame come from? - Type/Length: What protocol is in the payload? - Payload: Actual data (IP packet) - Frame Check Sequence: Error detection

652.4.3 MAC Address Format

Structure: 48 bits (6 bytes) = 12 hexadecimal digits

Common formats: - 01-23-45-67-89-AB (hyphens) - 01:23:45:67:89:AB (colons - most common) - 0123.4567.89AB (dots - Cisco style) - 0123456789AB (no separators - printed on labels)

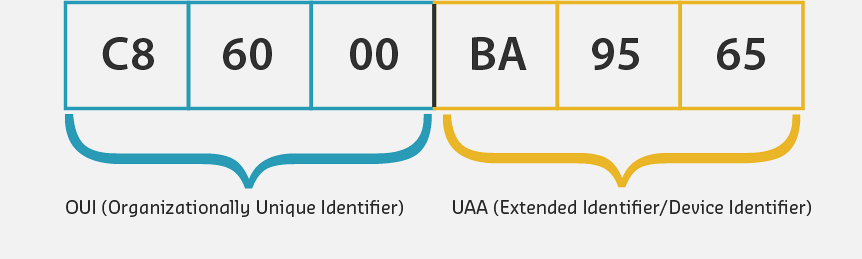

652.4.4 OUI (Organizationally Unique Identifier)

First 24 bits identify the manufacturer:

%% fig-alt: "MAC address OUI structure showing the 48-bit address divided into two parts: the first 24 bits form the Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI) assigned to the manufacturer, and the remaining 24 bits form the Device ID uniquely assigned by the manufacturer"

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph LR

subgraph MAC["MAC Address: 00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E"]

subgraph OUI["OUI (First 24 bits)"]

B1["00"]

B2["1A"]

B3["2B"]

end

subgraph DevID["Device ID (Last 24 bits)"]

B4["3C"]

B5["4D"]

B6["5E"]

end

end

OUI_Label["Manufacturer<br/>(Assigned by IEEE)"]

Dev_Label["Unique Device<br/>(Assigned by Vendor)"]

OUI -.-> OUI_Label

DevID -.-> Dev_Label

style B1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style B2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style B3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style B4 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style B5 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style B6 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style OUI_Label fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Dev_Label fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

Example OUIs: - 00:1A:2B - Cisco Systems - A4:CF:12 - Espressif (ESP32 manufacturer) - B8:27:EB - Raspberry Pi Foundation - DC:A6:32 - Raspberry Pi Trading

Lookup: IEEE OUI Search

652.4.5 Types of MAC Addresses

| Type | Address | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unicast | Unique device address | One-to-one communication | A4:CF:12:34:56:78 |

| Broadcast | All 1s | Send to all devices on network | FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF |

| Multicast | Group address | Send to specific group | 01:00:5E:xx:xx:xx |

IoT Note: Wireless MAC addresses may not be constant (privacy features), but each MAC on a network segment must be unique.

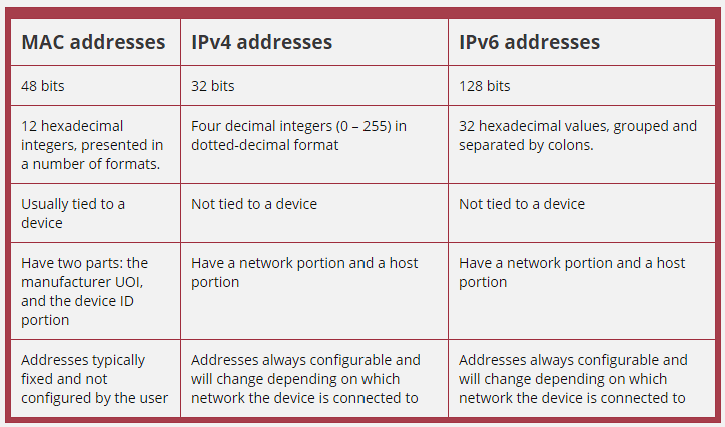

This variant presents the key differences between Layer 2 (MAC) and Layer 3 (IP) addressing side-by-side:

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#E67E22', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph MAC["MAC Address (Layer 2)"]

M1["48 bits = 6 bytes"]

M2["Burned into NIC"]

M3["Flat namespace"]

M4["Local delivery only"]

M5["Example: A4:CF:12:34:56:78"]

end

subgraph IP["IP Address (Layer 3)"]

I1["32 bits (IPv4) or 128 bits (IPv6)"]

I2["Assigned by DHCP or static"]

I3["Hierarchical (network.host)"]

I4["Global routing"]

I5["Example: 192.168.1.100"]

end

MAC -->|"Used by"| SW["Switch<br/>Forwards frames"]

IP -->|"Used by"| RT["Router<br/>Forwards packets"]

style M1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style M2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style M3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style M4 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style M5 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I1 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I3 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I4 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I5 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style SW fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style RT fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

MAC addresses work on local network segments (same switch), while IP addresses enable routing across different networks.

This variant shows how IP packets are encapsulated inside Ethernet frames for transmission:

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#E67E22', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085'}}}%%

graph LR

subgraph FRAME["Ethernet Frame (Layer 2)"]

FH["Frame Header<br/>Dest MAC, Src MAC"]

subgraph PACKET["IP Packet (Layer 3)"]

PH["Packet Header<br/>Dest IP, Src IP"]

subgraph SEG["TCP/UDP (Layer 4)"]

SH["Segment<br/>Port numbers"]

DATA["Application Data"]

end

end

FT["FCS"]

end

FH --> PH --> SH --> DATA --> FT

style FH fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style PH fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style SH fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style DATA fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style FT fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

Each layer adds its own header containing addressing information for that layer. This is encapsulation - layers wrap around each other like envelopes.

652.5 Internet Layer: IP Addressing

652.5.1 IPv4 vs MAC Addresses

Key difference: MAC addresses are typically fixed (burned into hardware), while IP addresses are configurable and change based on network.

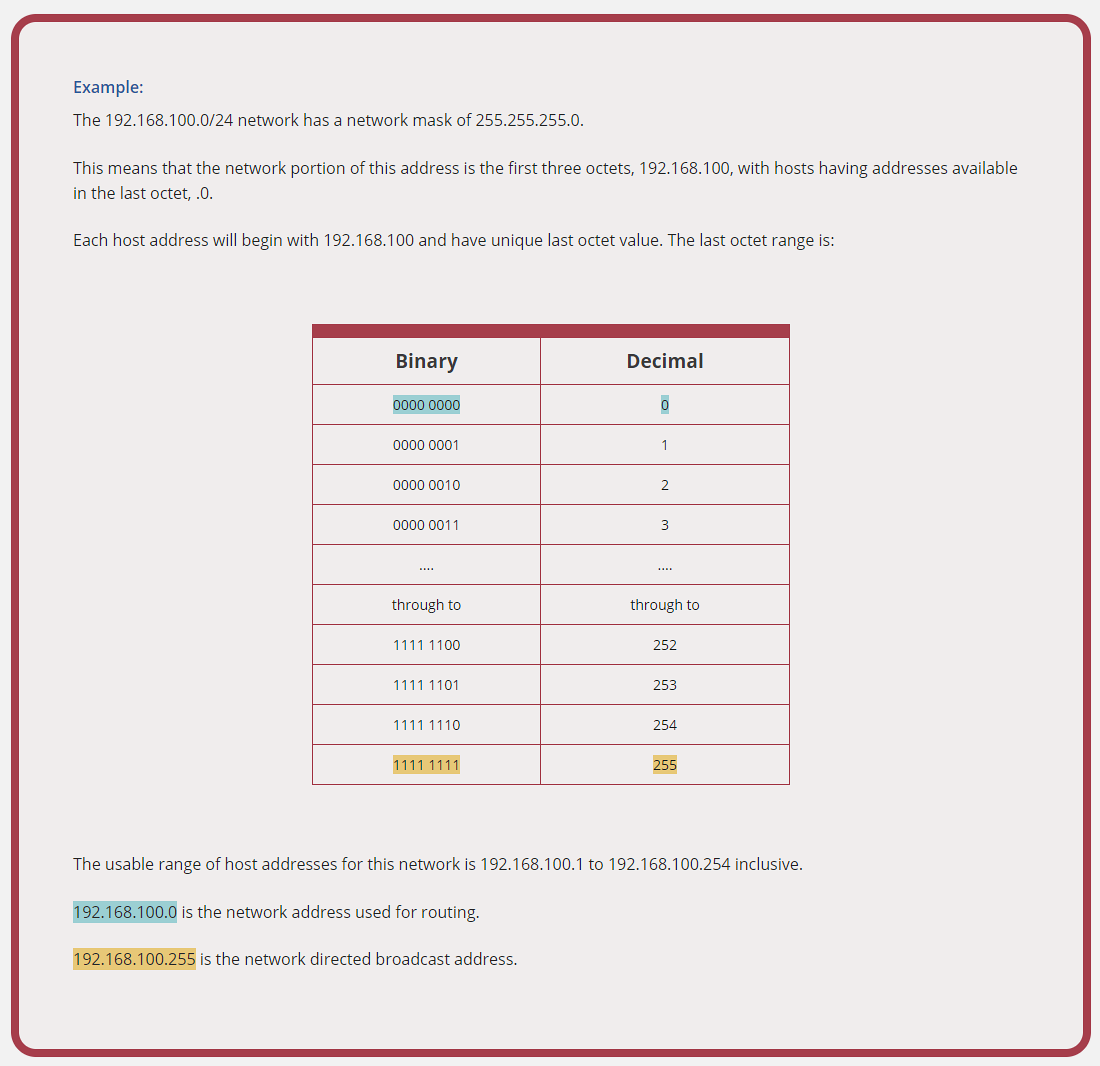

652.5.2 IPv4 Address Structure

Size: 32 bits (4 bytes)

Format: Four octets separated by dots (dotted-decimal notation)

Examples: - 10.0.122.57 - 172.16.11.202 - 192.168.100.4

Conversion: - Each octet: 0-255 (8 bits) - 10.0.122.57 in binary: 00001010.00000000.01111010.00111001

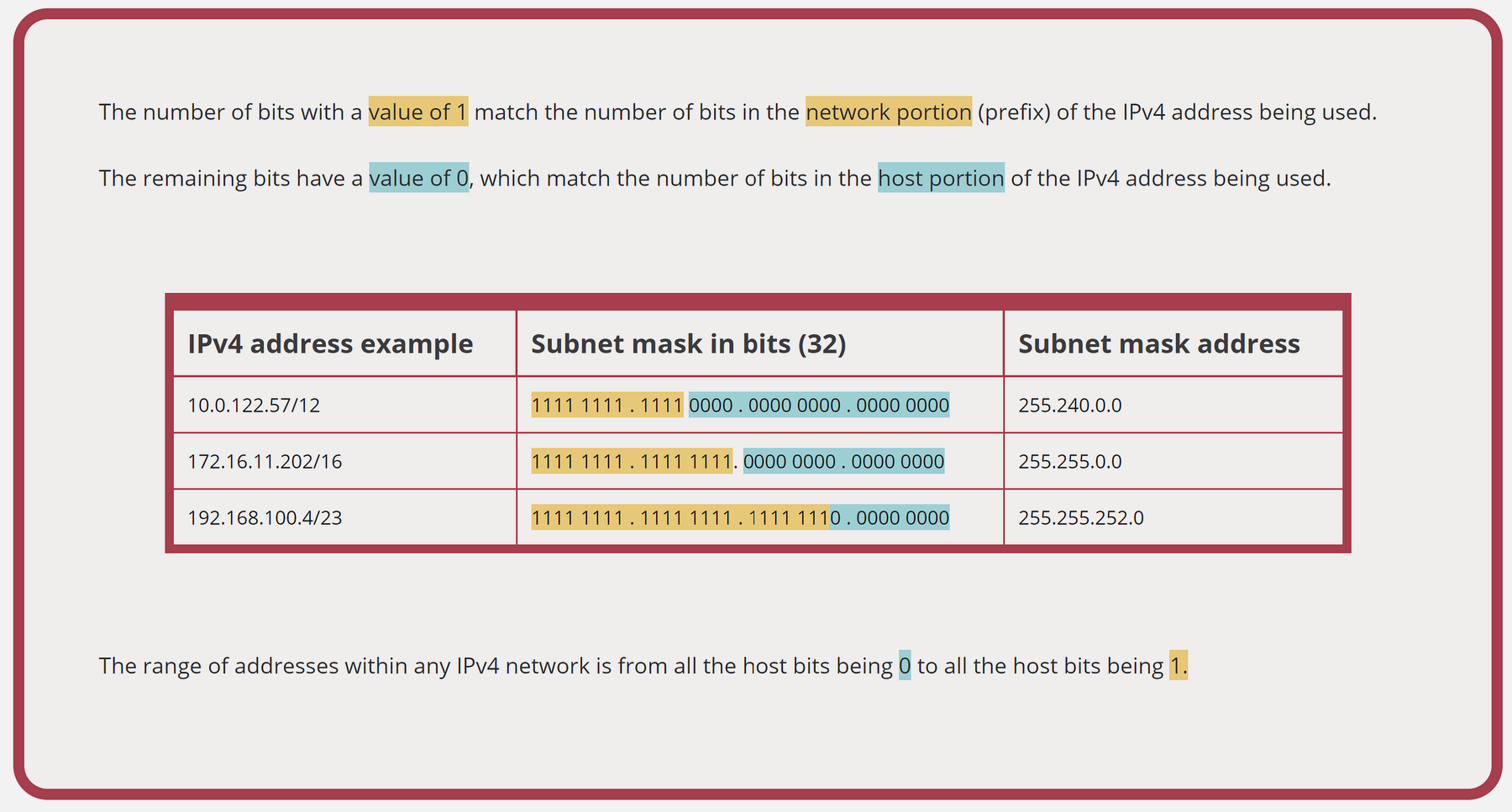

652.6 IPv4 Subnet Masks

652.6.1 Purpose

Subnet mask determines which part of the IP address is the network portion and which is the host portion.

652.6.2 Binary Perspective

Subnet mask: Most significant bits are 1, least significant bits are 0

Example:

%% fig-alt: "Subnet mask binary breakdown showing IP address 192.168.1.100 and subnet mask 255.255.255.0 in both decimal and binary format. The binary representation shows how the first 24 bits (all 1s in the mask) identify the network portion, while the last 8 bits (all 0s in the mask) identify the host portion"

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph IP["IP Address: 192.168.1.100"]

IP1["192<br/>11000000"]

IP2["168<br/>10101000"]

IP3["1<br/>00000001"]

IP4["100<br/>01100100"]

end

subgraph Mask["Subnet Mask: 255.255.255.0"]

M1["255<br/>11111111"]

M2["255<br/>11111111"]

M3["255<br/>11111111"]

M4["0<br/>00000000"]

end

subgraph Result["Network/Host Division"]

Net["Network Portion<br/>192.168.1<br/>(First 24 bits)"]

Host["Host Portion<br/>.100<br/>(Last 8 bits)"]

end

IP1 --> M1

IP2 --> M2

IP3 --> M3

IP4 --> M4

M1 --> Net

M2 --> Net

M3 --> Net

M4 --> Host

style IP1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IP2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IP3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IP4 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style M1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style M2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style M3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style M4 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Net fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Host fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

Result: - Network: 192.168.1.0 (where all host bits = 0) - Hosts: 192.168.1.1 to 192.168.1.254 - Broadcast: 192.168.1.255 (where all host bits = 1)

652.6.3 Common Subnet Masks

| Mask | CIDR | Network Bits | Host Bits | # of Hosts | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

255.255.255.252 |

/30 | 30 | 2 | 2 | Point-to-point links |

255.255.255.0 |

/24 | 24 | 8 | 254 | Small networks |

255.255.0.0 |

/16 | 16 | 16 | 65,534 | Large networks |

255.0.0.0 |

/8 | 8 | 24 | 16,777,214 | Huge networks |

652.6.4 Calculating Available Hosts

Formula: 2^(host bits) - 2

Why -2? - Network address (all host bits = 0) - used for routing - Broadcast address (all host bits = 1) - used for broadcast

Example: 255.255.255.0 (/24) - Host bits: 8 - Total addresses: 2^8 = 256 - Usable hosts: 256 - 2 = 254

Understanding subnet masks: Subnet Mask Explained

Visualizing subnet masks: Visualizing the Subnet Mask

Essential for IP network configuration and troubleshooting.

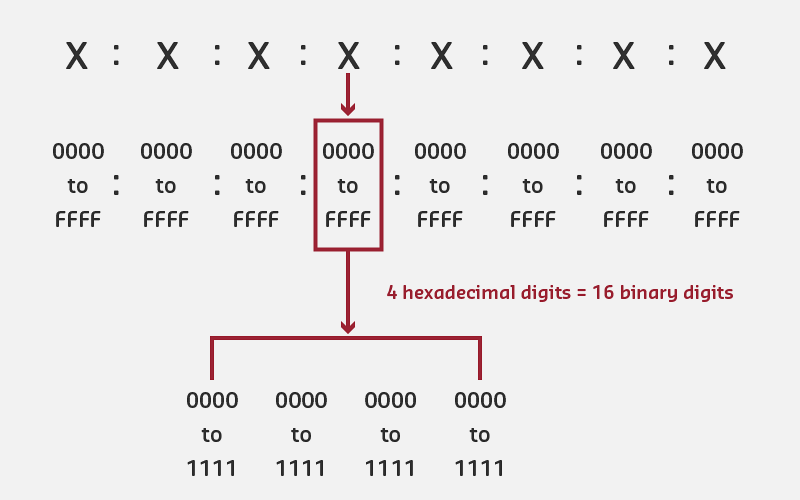

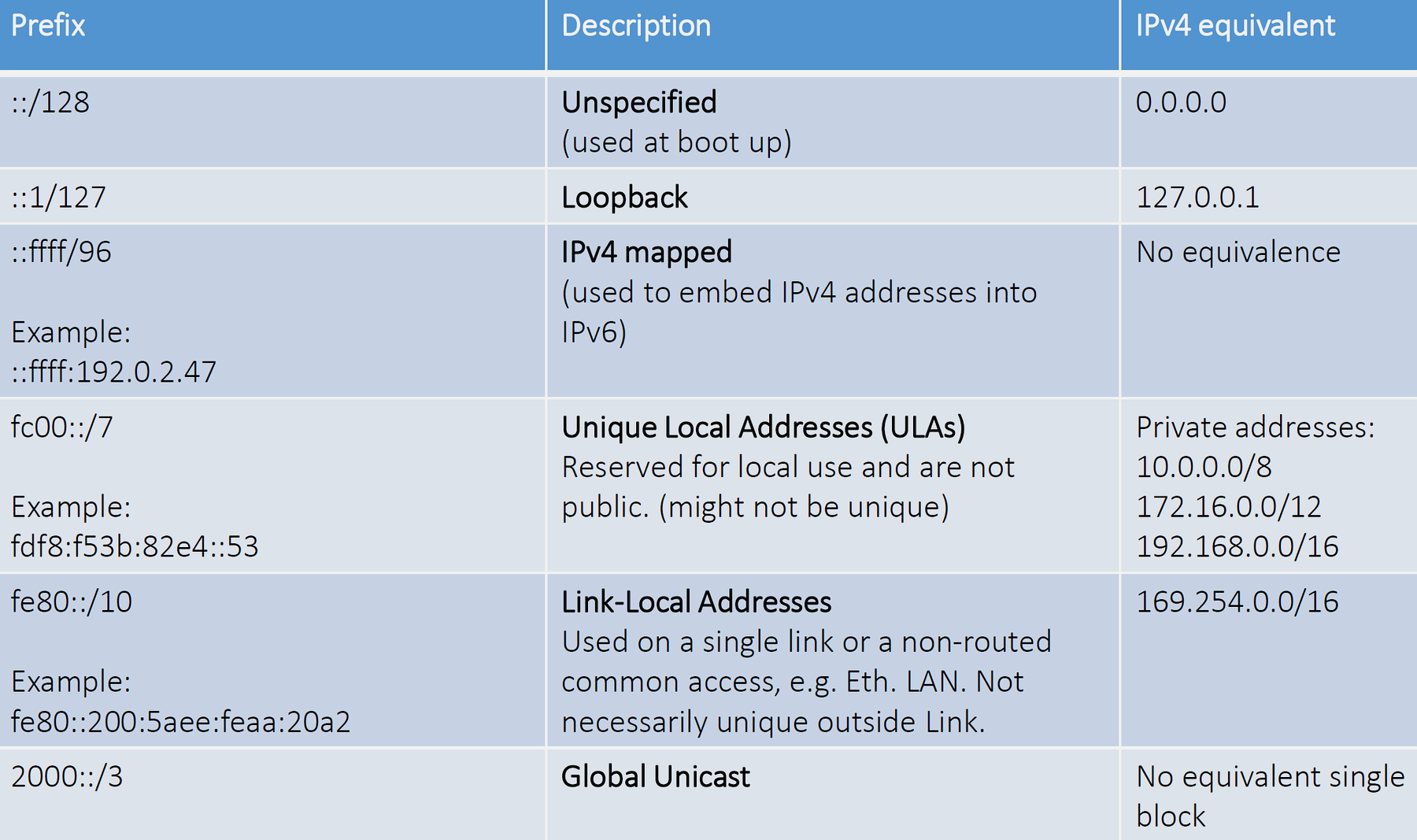

652.7 IPv6: The Future of IP Addressing

652.7.1 Why IPv6?

The Problem: - IPv4: 32 bits = ~4.3 billion addresses - Problem: IPv4 addresses exhausted! - IoT needs: Trillions of devices - NAT workaround: Complex, breaks end-to-end connectivity

The Solution: - IPv6: 128 bits = 3.4 × 10^38 addresses - Enough to assign: ~670 million addresses per square millimeter of Earth’s surface!

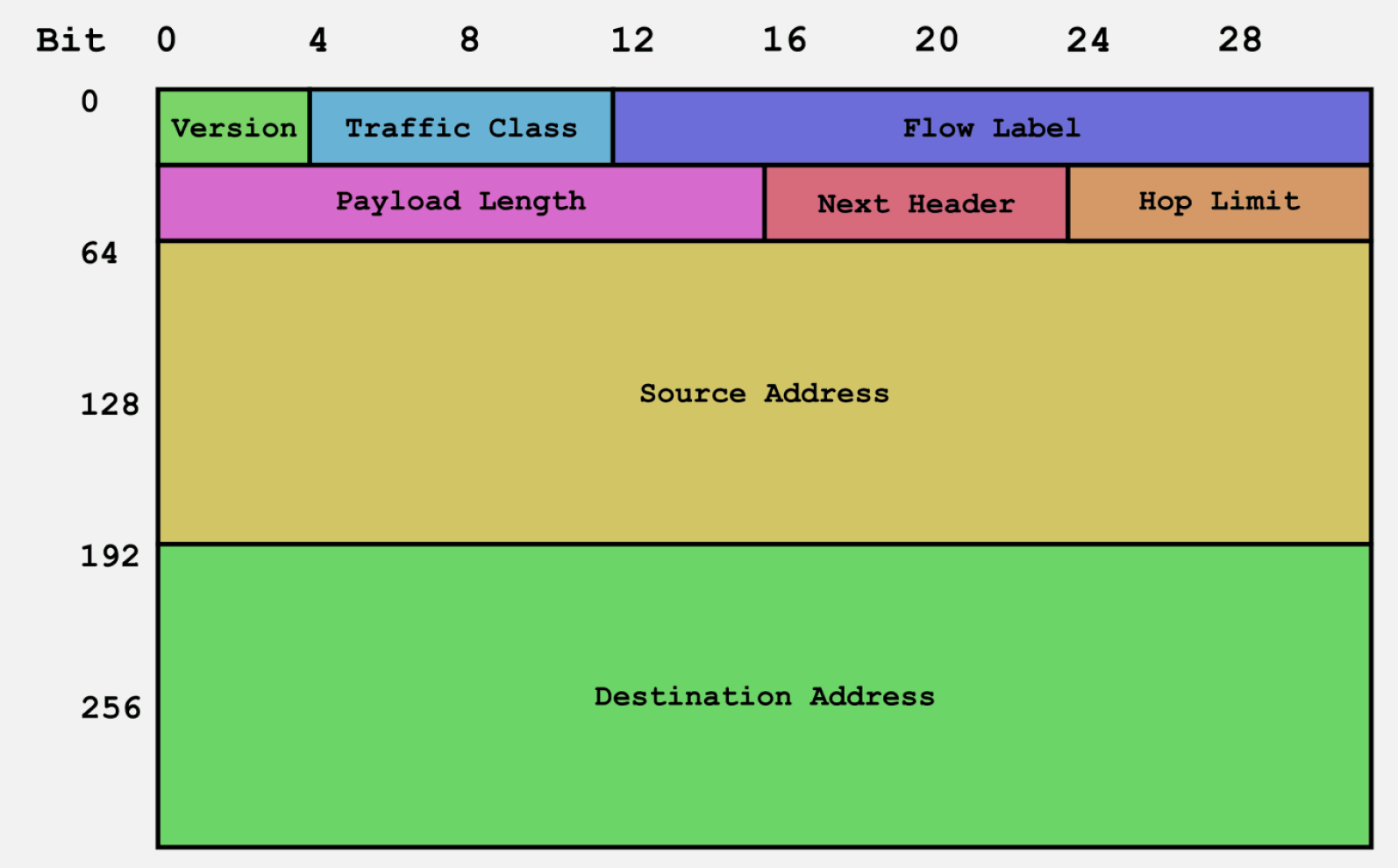

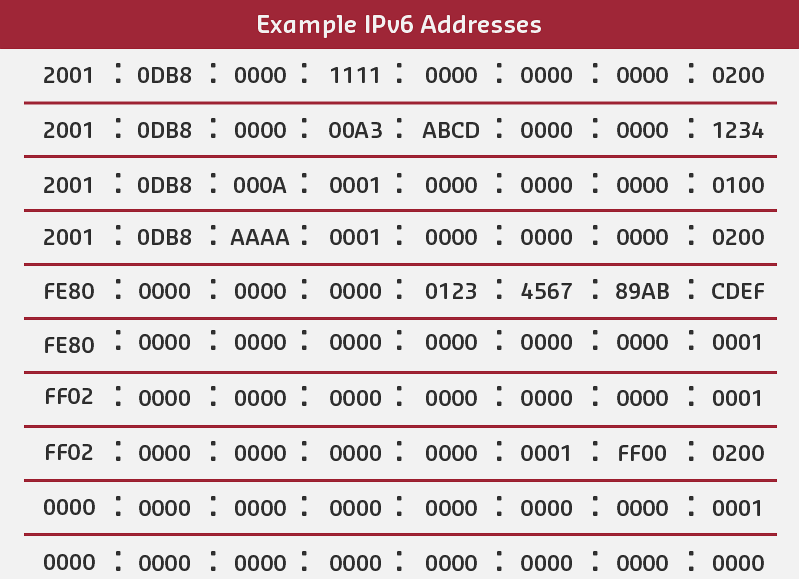

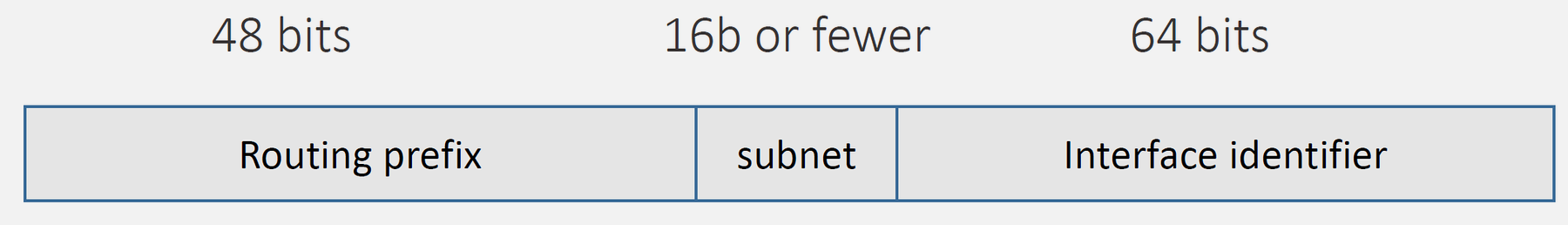

652.7.2 IPv6 Address Structure

Size: 128 bits (16 bytes)

Format: Eight groups of 16 bits (hextets), separated by colons

Full address example:

2001:0DB8:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0001Representation: Each hextet = 4 hexadecimal digits (0-9, A-F)

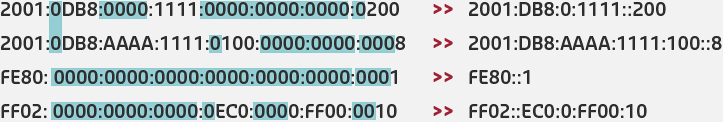

652.7.3 IPv6 Address Compression

Rules to shorten IPv6 addresses:

- Remove leading zeros in each hextet

- Replace consecutive groups of zeros with

::

Example compressions:

| Original | Compressed | Notes |

|---|---|---|

2001:0DB8:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0001 |

2001:DB8::1 |

Removed leading zeros, replaced zeros with :: |

FE80:0000:0000:0000:0202:B3FF:FE1E:8329 |

FE80::202:B3FF:FE1E:8329 |

Replaced middle zeros |

FF02:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0001 |

FF02::1 |

Multicast all-nodes address |

0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0001 |

::1 |

Localhost (loopback) |

0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000 |

:: |

Unspecified address |

Important: :: can only appear once in an address!

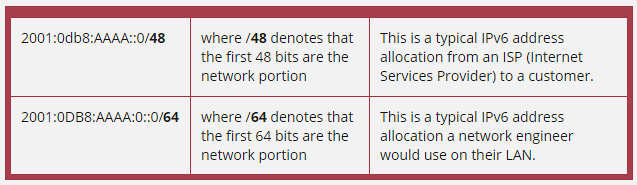

652.7.4 IPv6 Prefix Notation

No subnet masks needed! IPv6 uses prefix length instead.

Format: address/prefix

Example:

%% fig-alt: "IPv6 prefix notation breakdown showing address 2001:DB8:ACAD:1::1/64 divided into network prefix (first 64 bits: 2001:DB8:ACAD:1) and interface identifier (last 64 bits: ::1). The /64 suffix indicates the prefix length in bits"

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

Full["Full Address: 2001:DB8:ACAD:1::1/64"]

subgraph Prefix["Network Prefix (First 64 bits)"]

P1["2001"]

P2["DB8"]

P3["ACAD"]

P4["1"]

end

subgraph IID["Interface Identifier (Last 64 bits)"]

I1["0000"]

I2["0000"]

I3["0000"]

I4["0001"]

end

Notation["/64 = 64-bit prefix length"]

Full --> Prefix

Full --> IID

Full --> Notation

style Full fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style P1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style P2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style P3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style P4 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I1 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I3 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I4 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Notation fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

Network and Host Portions: - Network prefix (first 64 bits): 2001:DB8:ACAD:1 - Interface identifier (last 64 bits): ::1

Standard allocation: - /64 for end networks (LANs) - /48 for sites/organizations - /32 for ISPs

652.7.5 IPv6 Benefits for IoT

1. Abundant Addresses - Every device gets unique global address - No NAT complications - End-to-end connectivity

2. Simplified Configuration - Stateless Address Autoconfiguration (SLAAC) - Plug-and-play for IoT devices - DHCPv6 optional, not required

3. Improved Security - IPsec built into IPv6 - Better encryption support - Privacy extensions

4. Efficient Routing - Simplified header structure - Faster packet processing - Hierarchical addressing

652.8 MAC vs IP Addresses: Comparison

| Feature | MAC Address | IP Address (IPv4/IPv6) |

|---|---|---|

| Layer | Data Link (Layer 2) | Network (Layer 3) |

| Size | 48 bits | 32 bits (IPv4) / 128 bits (IPv6) |

| Assigned by | Manufacturer (OUI + unique) | Network administrator or DHCP |

| Scope | Local network segment | Global (routable across Internet) |

| Changes? | Usually fixed (hardware) | Changes when connecting to different networks |

| Format | 00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E |

192.168.1.100 or 2001:DB8::1 |

| Purpose | Local frame delivery | End-to-end routing |

| Uniqueness | Globally unique (in theory) | Unique within network |

Analogy: - MAC address = Your house (fixed location) - IP address = Your mailing address (changes when you move)

652.9 Address Resolution Protocol (ARP)

652.9.1 The Problem

To send data on a local network: - Know destination IP address (for routing) - Need destination MAC address (for frame delivery)

How to find the MAC address for a given IP address?

652.9.2 ARP Solution

Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) maps IP addresses to MAC addresses.

652.9.3 ARP Process

1. Host A wants to send data to 192.168.1.20 - Checks ARP cache (table of IP→MAC mappings) - If not found, sends ARP request

2. ARP Request (Broadcast) - Destination MAC: FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF (broadcast) - Message: “Who has IP 192.168.1.20? Tell 192.168.1.10” - All hosts on network receive request

3. ARP Reply (Unicast) - Host B recognizes its IP address - Sends reply: “192.168.1.20 is at MAC BB:BB:BB” - Reply sent directly to Host A (unicast)

4. Host A updates ARP cache - Stores mapping: 192.168.1.20 → BB:BB:BB - Cache entry expires after timeout (typically 2-20 minutes) - Now can send Ethernet frames to Host B

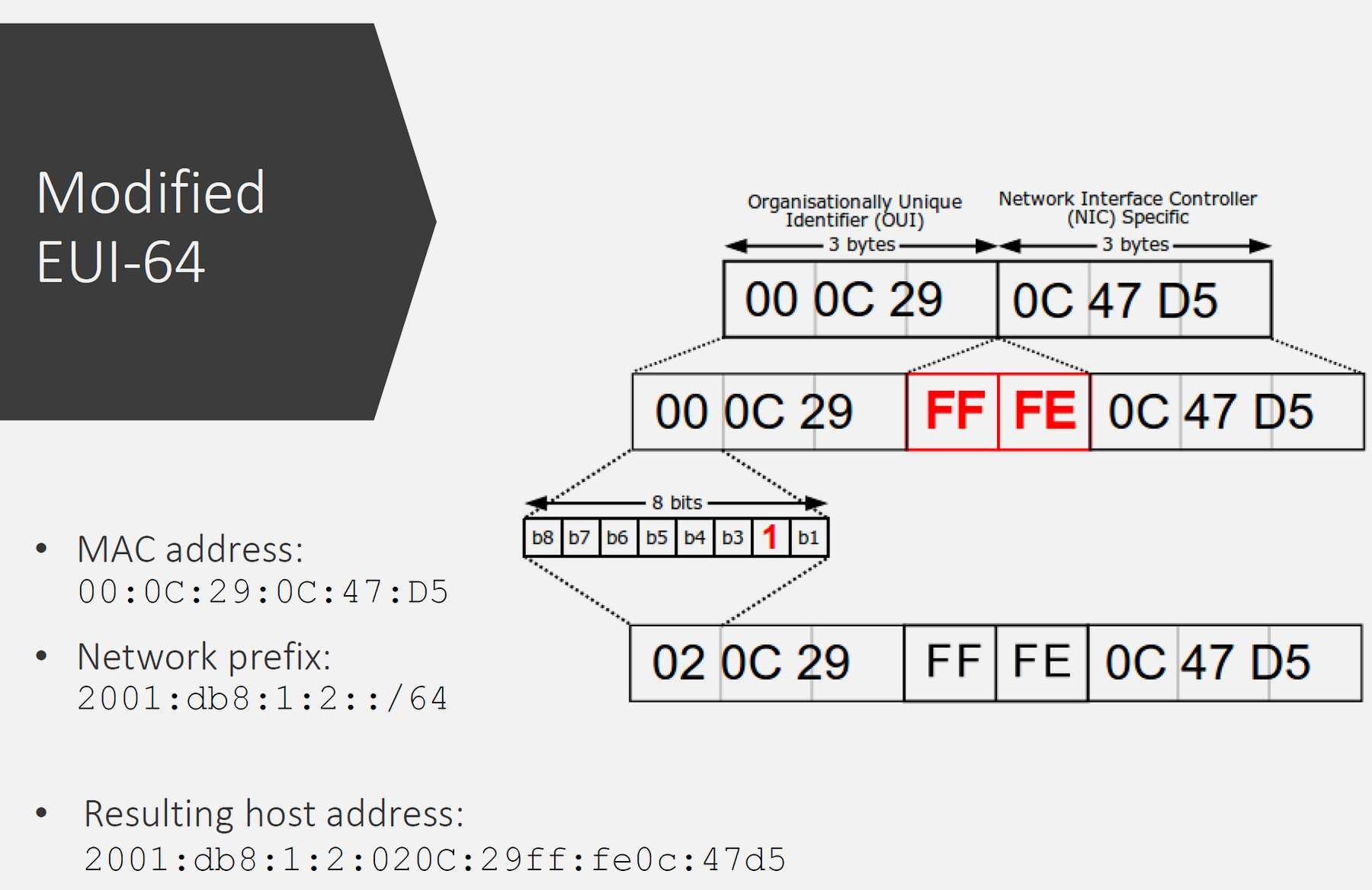

652.9.4 IPv6 Equivalent: NDP

Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP) serves the same purpose for IPv6: - Maps IPv6 addresses to MAC addresses - Uses ICMPv6 messages - More efficient than ARP - Includes additional features (router discovery, address autoconfiguration)

652.10 💻 Hands-On Labs

652.10.1 Lab 1: Explore Network Configuration

Objective: Examine IP, subnet mask, gateway, and MAC addresses on your device.

652.10.1.1 Windows:

ipconfig /allLook for: - IPv4 Address - Subnet Mask - Default Gateway - Physical Address (MAC) - DNS Servers

652.10.1.2 macOS/Linux:

ifconfig

# OR

ip addr show652.10.1.3 ESP32 Code:

#include <Wi-Fi.h>

const char* ssid = "YourNetwork";

const char* password = "YourPassword";

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

Wi-Fi.begin(ssid, password);

while (Wi-Fi.status() != WL_CONNECTED) {

delay(500);

Serial.print(".");

}

Serial.println("\n\n=== Network Configuration ===");

Serial.print("IP Address: ");

Serial.println(Wi-Fi.localIP());

Serial.print("Subnet Mask: ");

Serial.println(Wi-Fi.subnetMask());

Serial.print("Gateway: ");

Serial.println(Wi-Fi.gatewayIP());

Serial.print("DNS: ");

Serial.println(Wi-Fi.dnsIP());

Serial.print("MAC Address: ");

Serial.println(Wi-Fi.macAddress());

}

void loop() {

// Nothing

}652.10.2 Lab 2: View ARP Table

Objective: See IP-to-MAC address mappings on your system.

652.10.2.1 Windows:

arp -a652.10.2.2 macOS/Linux:

arp -a

# OR

ip neigh showExpected output:

Internet Address Physical Address Type

192.168.1.1 aa-bb-cc-dd-ee-ff dynamic

192.168.1.20 11-22-33-44-55-66 dynamic652.10.3 Lab 3: Subnet Calculation Practice

Given: - IP: 192.168.10.50 - Subnet mask: 255.255.255.0

Calculate: 1. Network address? 2. Broadcast address? 3. First usable host? 4. Last usable host? 5. Number of usable hosts?

Show Answers

- Network address:

192.168.10.0 - Broadcast address:

192.168.10.255 - First usable host:

192.168.10.1 - Last usable host:

192.168.10.254 - Number of usable hosts: 254 (2^8 - 2)

652.11 Knowledge Check

Test your understanding of network layers, protocol encapsulation, and addressing with these questions.

652.12 🎯 Quiz: Test Your Understanding

Let’s implement comprehensive Python tools for analyzing network layers, protocol encapsulation, and addressing:

652.12.1 Protocol Encapsulation and Layer Simulator

652.12.2 IPv4/IPv6 Address and Subnet Calculator

652.12.3 ARP Table and MAC/IP Mapping Simulator

652.13 Visual Reference Gallery

These AI-generated SVG figures provide alternative visual representations of network addressing and protocol layering concepts. Each figure uses the IEEE color palette for consistency.

652.14 Additional Visual References

The OSI model provides the theoretical framework for understanding network communication, with each layer performing specific functions from physical transmission to application services.

The Data Link layer handles MAC addressing, framing, and error detection - critical functions for local network frame delivery between adjacent devices.

Understanding encapsulation reveals how data transforms as it passes through network layers, with each layer adding its own header for addressing and control.

652.15 Summary

This chapter provided hands-on implementation of network addressing and protocol layering concepts:

- MAC addresses (48-bit) identify network interfaces at Layer 2, with first 24 bits (OUI) identifying manufacturer and last 24 bits providing device-specific identifier

- IPv4 addressing (32-bit) uses dotted-decimal notation with subnet masks to divide networks into network and host portions, enabling hierarchical routing

- Subnet masks determine network boundaries: /24 provides 254 usable hosts, /30 provides 2 (point-to-point links), calculated as 2^(host bits) - 2 (network + broadcast reserved)

- IPv6 (128-bit) solves address exhaustion with 340 undecillion addresses, supporting auto-configuration (SLAAC), built-in security (IPsec), and compression (6LoWPAN) for IoT

- ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) maps Layer 3 IP addresses to Layer 2 MAC addresses through broadcast requests and unicast replies, enabling local frame delivery

- Encapsulation simulator demonstrates header addition at each layer: application data → UDP/TCP segment → IP packet → Ethernet frame → physical bits

- Python implementations provide practical tools: IPv4/IPv6 calculators, subnet planners, ARP table simulators, and protocol overhead analyzers showing efficiency vs payload size

652.16 What’s Next

Having implemented addressing and analyzed protocol encapsulation, consolidate your understanding with comprehensive review and assessment:

- Layered Models: Review: Test mastery of OSI/TCP-IP models, encapsulation, addressing, and IoT reference architectures with scenario-based questions

- Routing protocols: Explore how routers use routing tables and algorithms to guide packets across networks using the Layer 3 addresses you’ve learned

- Wireless IoT technologies: Apply layering concepts to Wi-Fi, Bluetooth LE, LoRaWAN, and Zigbee, understanding which OSI layers each technology implements

- Network design patterns: Design complete IoT networks from edge sensors through gateways to cloud, selecting appropriate protocols and addressing schemes at each layer