184 Power Management and Device Interfaces

184.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Analyze Power Budgets: Calculate power consumption for battery-powered IoT devices

- Design Memory Architecture: Plan RAM, ROM, and flash storage requirements for embedded applications

- Assess Connectivity Options: Select appropriate communication interfaces (GPIO, SPI, I2C, UART) for sensor integration

- Configure GPIO Modes: Select appropriate input/output modes for sensors and actuators

- Implement PWM Control: Use pulse width modulation for LED brightness, motor speed, and servo control

184.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- MCU vs MPU Selection: Understanding the fundamental differences between microcontrollers and microprocessors

- Basic Electronics: Understanding of voltage, current, resistance, and digital logic (HIGH/LOW states)

184.3 IoT Device Specifications and Characteristics

Platforms for the IoT are continuously being developed and released in ever-increasing numbers and varieties. It is necessary to understand the underlying specifications of these devices to evaluate and compare new devices objectively.

We can characterize IoT devices in terms of these high-level capabilities:

- Power management

- Sensors and actuators

- Processing capability

- Connectivity

- Operating System

184.4 Power Management

Power management is a critical concern for most IoT devices. Many are:

- Wearable (who wants to recharge their smartwatch three times a day?)

- Installed in remote or inaccessible areas

- Intended to run for long periods without maintenance

- Solar powered or energy scavenging devices

Sleep modes: Placing devices into a sleep or low-power mode may alleviate some power requirements, but the device itself must be capable of entering this mode and being awakened by an appropriate method.

Communications impact: One major constraint on power is not just the micro itself, but the communications protocols implemented on the platform.

Power-influencing factors:

- Clock rate of the CPU

- Number of processor cores

- Included peripherals (USB, Bluetooth, Ethernet ports)

- Processor load

- Supply voltage levels

MCU Power Mode Architecture: Modern microcontrollers implement hierarchical power states to balance responsiveness with energy efficiency. Active mode (full clock speed, all peripherals enabled) suits short computation bursts but drains batteries in hours—ESP32 at 160mA consumes a 2000mAh battery in 12.5 hours. Idle mode (clock running, CPU halted via WFI/WFE instructions) provides instant wake-up (<1µs) while reducing current 50-70%, ideal for event-driven systems responding to interrupts. Light sleep (CPU and high-speed clocks stopped, RAM retained, RTC and wake-up sources active) achieves 100-1000x reduction while maintaining fast wake-up (100µs-10ms), suitable for periodic sensing with <1-minute intervals. Deep sleep (all clocks stopped except low-frequency 32kHz RTC, minimal RAM retained, GPIO wake-up only) reaches 10,000x reduction (10µA typical) but requires 1-100ms wake-up including clock stabilization and peripheral re-initialization—optimal for hourly/daily reporting. Wake-up sources vary by mode: light sleep supports timers and GPIO; deep sleep requires external interrupts, RTC alarms, or watchdog triggers. Critical tradeoff: Deep sleep extending wake-up time from 1ms to 50ms adds transition energy overhead—for 1-second active periods every minute, 50ms wake-up wastes 8% of duty cycle versus 0.2% for 1ms wake-up. Choose lightest sleep mode that meets battery life targets while respecting wake-up latency requirements.

Leakage Current: The Hidden Battery Drain: While dynamic power (P = CV²f) scales with clock frequency and can be eliminated by stopping clocks, leakage current flows continuously in powered CMOS transistors even when idle, setting the lower bound on sleep mode consumption. Three physical mechanisms dominate: (1) Subthreshold leakage—transistors never completely turn off; current flows below threshold voltage with exponential Vt and temperature dependence (10x increase per 100°C or 100mV Vt reduction); (2) Gate oxide tunneling—quantum mechanical leakage through ultra-thin gate dielectrics (significant below 2nm oxide thickness in modern processes); (3) Junction leakage—reverse-biased PN junction currents increasing with temperature. Process node scaling exacerbates leakage: transitioning from 180nm to 28nm increases leakage current 100-1000x due to thinner oxides and reduced Vt needed to maintain switching speed. Temperature impact is severe: a chip drawing 1µA at 25°C may consume 10µA at 85°C (industrial), halving battery life in hot environments like automotive or solar-heated outdoor sensors. Mitigation strategies: (1) Body biasing—adjust transistor threshold voltage by biasing body terminal, trading speed for 2-10x leakage reduction in sleep modes; (2) Power gating—completely disconnect power domains with PMOS switches, reducing leakage to junction current only (<1nA) but losing all state; (3) Multi-Vt libraries—use high-Vt transistors (lower leakage) for non-critical paths, low-Vt (faster but leaky) for critical paths; (4) Voltage scaling—reduce Vdd in sleep modes (quadratic power reduction). Design implications: For 10-year battery life, total average current must be <1µA. If deep sleep draws 10µA, duty cycle must be <10% active, or consider power-gated shutdown losing RAM. Ultra-low-power MCUs like MSP430 or nRF52 achieve 0.1-0.5µA sleep via aggressive power gating and body biasing.

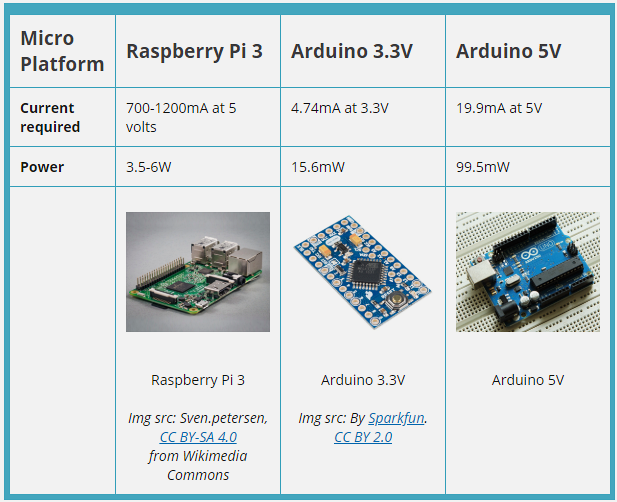

Power Comparison Example:

| Platform | Operating Mode | Current Draw | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arduino Uno (ATmega328) | Active @ 16MHz, 5V | ~45 mA | Simple sensor reading |

| Sleep mode | ~15 mA | Battery operation | |

| ESP32 (Wi-Fi/BLE SoC) | Active Wi-Fi TX | ~160-260 mA | Connected IoT |

| Deep sleep | ~10 μA | Long battery life | |

| Raspberry Pi Zero | Idle | ~100-120 mA | Gateway/Edge compute |

| Active with Wi-Fi | ~150-200 mA | Full OS required |

Note: If you connect additional components (e.g., camera module ~250mA), the current requirement increases. Sensors and actuators usually require power to operate, so total device power consumption increases with the number of attached components.

Challenge: Deploy 500 battery-powered soil moisture sensors across a 1,000-acre farm. Sensors must last 5+ years without battery replacement, report hourly, and cost under $20 per unit installed.

Hardware Selection Process:

| Requirement | Raspberry Pi Zero ($15) | ESP32 ($5) | nRF52840 ($6) | Selected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power (avg) | 100mA (2.4W hours/day) | 20mA (0.48W hours/day) | 5mA (0.12W hours/day) | nRF52840 |

| Battery Life | 16 days (2000mAh) | 104 days | 416 days x 4 = 5.7 years | nRF52840 |

| Cost @ 500 units | $7,500 | $2,500 | $3,000 | nRF52840 |

| Wireless | Wi-Fi (high power) | Wi-Fi+BLE (medium) | BLE Mesh (ultra-low) | nRF52840 |

| OS Needed? | Yes (Linux) | No (bare-metal) | No (Zephyr RTOS) | No OS |

| GPIO/ADC | 40 GPIO, no ADC | 30 GPIO, 12-bit ADC | 32 GPIO, 12-bit ADC | nRF52840 |

Actual Implementation (Selected: nRF52840):

Power Budget Breakdown:

- Deep sleep (23.5 hours/day): 0.4µA x 23.5h = 0.0094 mAh/day

- Wake + sensor read (10 sec/hour x 24): 15mA x 0.067h = 1 mAh/day

- BLE transmission (2 sec/hour x 24): 8mA x 0.013h = 0.1 mAh/day

- Total: 1.11 mAh/day -> 2000mAh battery = 1,802 days (4.9 years)

Code Architecture (bare-metal, no OS overhead):

// Ultra-low power operation

void main(void) {

nrf_gpio_cfg_input(MOISTURE_PIN, NRF_GPIO_PIN_PULLDOWN);

nrf_drv_saadc_init(NULL, saadc_callback);

while(1) {

nrf_pwr_mgmt_run(); // Deep sleep (0.4µA)

// Wake every 60 minutes via RTC

if (hour_elapsed) {

read_moisture_sensor(); // 15mA for 10 sec

transmit_ble_mesh(); // 8mA for 2 sec

hour_elapsed = false;

}

}

}Why NOT Raspberry Pi Zero?:

- 100mA average power = 60x higher than nRF52840

- Battery would last only 20 days instead of 5 years

- Requires microSD card (additional failure point in dirt/moisture)

- Linux boot time wastes power on every wake cycle

Why NOT ESP32?:

- Wi-Fi range issues in farm environment (need mesh networking)

- 20mA average = 12x higher power than nRF52840

- Wi-Fi association overhead (500ms) vs BLE mesh (50ms)

Deployment Results (500 sensors, 2 years operational):

- Average battery life: 4.8 years (98% of calculated)

- Only 3 premature failures (0.6% failure rate)

- Total cost: $3,000 hardware + $2,000 installation = $5,000 vs $25,000 (if using RPi with solar panels)

- Farmer replaced 6 batteries vs 500 batteries annually = $60 vs $5,000/year maintenance

Key Lesson: Matching hardware to requirements saves money and maintenance at scale. The nRF52840’s ultra-low power consumption and mesh networking were critical for battery life and farm coverage. Overspeccing with Raspberry Pi would have required expensive solar panels and frequent maintenance.

184.5 Sensors and Actuators

Sensors and actuators are how IoT solutions interact with the world.

184.5.1 Sensors and Data Acquisition

Data Acquisition (DAQ) is the process of measuring real-world conditions and converting these measurements into digital readings at fixed-time intervals (the data sample rate).

Signal conditioning is needed to:

- Filter usable data from signals (remove noise)

- Scale raw sensor readings

- Convert analog to digital (ADC) or digital to analog (DAC)

184.5.2 Resolution Requirements

The resolution of a sensor represents the smallest amount of change that the sensor can reliably read, related to the size of the numeric value representing raw sensor readings.

Example: Measuring temperature in a chemical process to within 0.1°C:

- Temperature range: 0-100°C

- Required accuracy: 0.1°C

- Required ADC resolution: 10 bits

- 10 bits = 2¹⁰ = 1024 possible values

- 100°C / 1024 = 0.098°C accuracy

- Therefore: need at least 10-bit ADC

In practical systems, electrical noise usually requires building in higher resolution than the minimum calculated.

184.5.3 Actuators

Actuators convert electrical signals to physical actions:

- LEDs, speakers, screens

- Motors, solenoids

- Pumps, valves

Design consideration: When designing a system, consider the ports necessary to drive these devices. For example, moving a servo motor requires a Pulse Width Modulated (PWM) pin.

184.6 GPIO and PWM Fundamentals

General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pins are the primary interface between a microcontroller and the physical world. Understanding GPIO modes and Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) is essential for controlling sensors and actuators in IoT systems.

184.6.1 GPIO Pin Modes Interactive Tool

GPIO pins can be configured in different modes depending on whether you’re reading inputs (sensors, buttons) or controlling outputs (LEDs, motors). Each mode has specific electrical characteristics and use cases.

Always use pull-up or pull-down resistors for inputs - Never leave inputs floating (INPUT mode alone), as this causes unpredictable behavior and increases power consumption

Respect current limits - Most MCU GPIO pins are rated for 12-40mA maximum; use transistors or MOSFETs for higher current loads (motors, relays, high-power LEDs)

Check voltage compatibility - Never connect 5V signals directly to 3.3V MCU pins without level shifting; this can permanently damage the microcontroller

Consider total current budget - The sum of all GPIO currents must stay within MCU limits (typically 100-200mA total); exceeding this can cause voltage drops and system instability

184.6.2 PWM Duty Cycle Interactive Tool

Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) allows microcontrollers to simulate analog output by rapidly switching a digital pin between HIGH and LOW states. The duty cycle (percentage of time in HIGH state) controls the average voltage and power delivered to connected devices.

Choose appropriate frequency - LEDs need >100 Hz (avoid flicker), motors benefit from >20 kHz (silent operation), servos require exactly 50 Hz

Account for perception non-linearity - Human eyes perceive brightness logarithmically; use gamma correction (duty^0.45) for smooth LED fading

Mind the dead zone for motors - Most DC motors won’t start moving until PWM exceeds 15-25% duty cycle due to static friction

Use hardware PWM when available - Software PWM (bit-banging) is CPU-intensive and inconsistent; prefer dedicated PWM peripherals (ESP32 LEDC, Arduino Timer1)

Filter PWM for true analog - Add RC low-pass filter (e.g., 1kΩ + 10µF) to convert PWM to smooth DC voltage for analog applications

Option A (On-Device Processing): Edge device performs all computation locally (filtering, anomaly detection, compression) before transmitting results. Bandwidth: 90-99% reduction (send alerts, not raw data). Latency: sub-millisecond for local decisions. Power: higher per-cycle but fewer transmissions. Example: ESP32 running TensorFlow Lite Micro for vibration anomaly detection.

Option B (Gateway Offloading): Edge device transmits raw sensor data to a nearby gateway (Raspberry Pi, industrial PC) for processing. Simpler edge firmware, easier updates (change gateway code, not 1000s of device firmwares), more powerful processing available (GPU, multi-core). Bandwidth: higher between edge and gateway, but gateway compresses for cloud. Latency: 5-50ms to gateway.

Decision Factors:

Choose On-Device Processing when: Bandwidth is expensive or limited (cellular IoT at $0.50/MB, satellite), real-time response required (<10ms for safety systems), privacy-sensitive data shouldn’t leave device (medical, industrial secrets), or devices operate in disconnected environments (agriculture, mining).

Choose Gateway Offloading when: Edge devices are severely resource-constrained (<32KB RAM, 8-bit MCU), processing algorithms change frequently (ML model updates weekly), gateway already exists in deployment (smart home hub, factory PLC), or processing requires resources unavailable on edge (GPU for video analytics, large ML models).

Hybrid pattern: Edge performs time-critical decisions (emergency shutoff) and basic filtering; gateway handles complex analytics and ML inference; cloud provides long-term storage and fleet-wide analytics. This three-tier approach balances latency, cost, and capability. Typical data reduction: raw sensor (100%) -> edge filtered (10%) -> gateway compressed (2%) -> cloud summary (0.5%).

184.7 Processing Capability

IoT devices capture, process, analyze, and transform sensor data and/or interact with the environment via actuators and displays. To do so, they require processing and data storage capabilities.

184.7.1 Two Main Approaches

Where to process data:

Cloud-based solution: Transmit possibly large volumes of data to a cloud server or data center for analysis

Edge approach: Perform data analysis at the edges of a network where data is captured, either on the devices themselves or on a nearby gateway device

- Advantage: Aggregate and filter data as collected; only salient data transmitted to cloud

- Advantage: Reduces required network bandwidth

- Trade-off: Requires significantly more powerful processor within IoT device

184.8 Knowledge Check

184.9 Summary

This chapter covered power management and device interfaces for IoT systems:

- Power Management: ESP32 demonstrates dramatic power ranges (160mA Wi-Fi active vs 10µA deep sleep); duty cycling achieves 8mA average consumption for 10-day battery life from 2000mAh

- Sleep Modes: Active, idle, light sleep, and deep sleep modes offer 10,000x power reduction tradeoffs against wake-up latency (1µs to 100ms)

- Leakage Current: Temperature doubles leakage every ~10°C; ultra-low-power MCUs achieve 0.1-0.5µA sleep via power gating and body biasing

- GPIO Configuration: Input modes (floating, pull-up, pull-down) determine idle state and power consumption; output modes source/sink 12-40mA per pin with critical voltage compatibility requirements between 3.3V and 5V systems

- PWM Control: Pulse Width Modulation simulates analog output through duty cycle variation; 8-16 bit resolution enables precise control of LED brightness, motor speed, and servo positions

- Sensor Resolution: 10-bit ADC provides 0.098°C accuracy for 0-100°C temperature range; higher resolution counters electrical noise in practical systems

- Processing Tradeoffs: On-device processing reduces bandwidth 90-99% with sub-millisecond latency; gateway offloading simplifies firmware and enables GPU/ML processing

184.10 What’s Next

The next chapter covers IoT System-on-Chip Architecture, exploring the internal structure of modern IoT SoCs including CPU cores, RF subsystems, hardware accelerators, and power management integration.