%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '15px'}}}%%

graph TB

SP["Setpoint"] --> Error["Error<br/>Calculation<br/>(SP - PV)"]

PV["Process<br/>Variable<br/>(Measured)"] --> Error

Error --> P["P Term:<br/>Kp x error<br/>(Current Error)"]

Error --> I["I Term:<br/>Ki x integral<br/>(Accumulated)"]

Error --> D["D Term:<br/>Kd x derivative<br/>(Rate of Change)"]

P --> Sum["Σ<br/>Sum"]

I --> Sum

D --> Sum

Sum -->|Control Signal| Plant["Process/<br/>Plant"]

Plant -->|Output| PV

style Error fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style P fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style I fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style D fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Sum fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style Plant fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

223 PID: Control Theory

223.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Implement PID Controllers: Design Proportional-Integral-Derivative controllers for IoT actuator systems

- Understand PID Mathematics: Apply the PID equation and calculate P, I, and D term contributions

- Analyze System Response: Evaluate system behavior including overshoot, settling time, and steady-state error

- Select PID Configurations: Choose appropriate P, PI, PD, or full PID control for specific applications

Core Concept: PID control combines three complementary strategies - P (Proportional) reacts to current error, I (Integral) accumulates past errors to eliminate offset, and D (Derivative) predicts future error to prevent overshoot. Why It Matters: Each term solves a specific problem that the others cannot - P alone leaves steady-state error, adding I eliminates that error but may overshoot, and D provides the damping needed for smooth, stable control. Key Takeaway: Think of PID as past-present-future: I remembers the past, P responds to the present, D anticipates the future - together they achieve what no single term can accomplish alone.

223.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- Feedback Fundamentals: Understanding feedback concepts and negative feedback

- Open-Loop and Closed-Loop Systems: Comparing control architectures

- Sensor Fundamentals: Sensors for feedback measurement

The Problem: Bang-bang (on/off) control is fundamentally inefficient:

- Overshoot: System blows past the setpoint, then must reverse direction

- Oscillation: Continuous cycling between “too hot” and “too cold” (or fast/slow)

- Actuator Wear: Frequent switching damages relays, compressors, and motors

- Energy Waste: Heating then immediately cooling wastes significant energy

What We Need:

- Smooth approach to setpoint without overshoot

- Fast recovery from disturbances

- Stable operation with no oscillations

- A general solution that works across different system types

The Solution: PID control uses three complementary strategies to achieve optimal control.

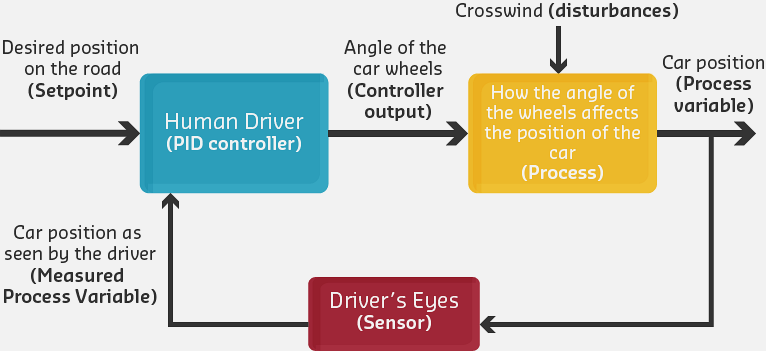

223.3 PID Controller Overview

While simple closed-loop systems provide basic feedback, achieving optimal performance often requires more sophisticated control algorithms. The PID controller is the most widely used feedback control algorithm in industrial and IoT applications.

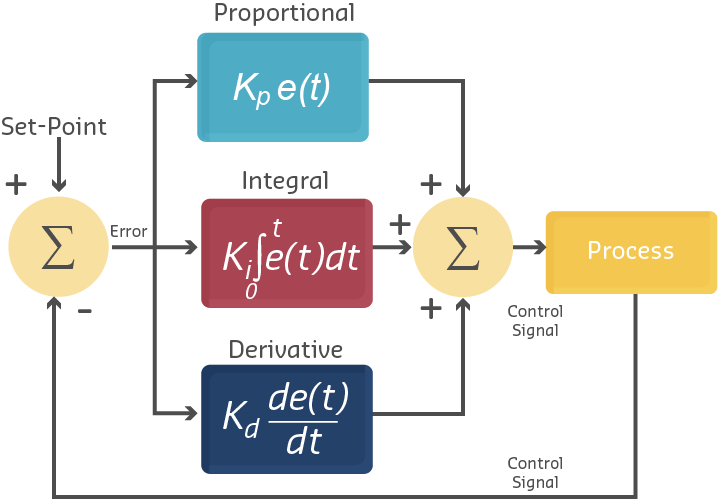

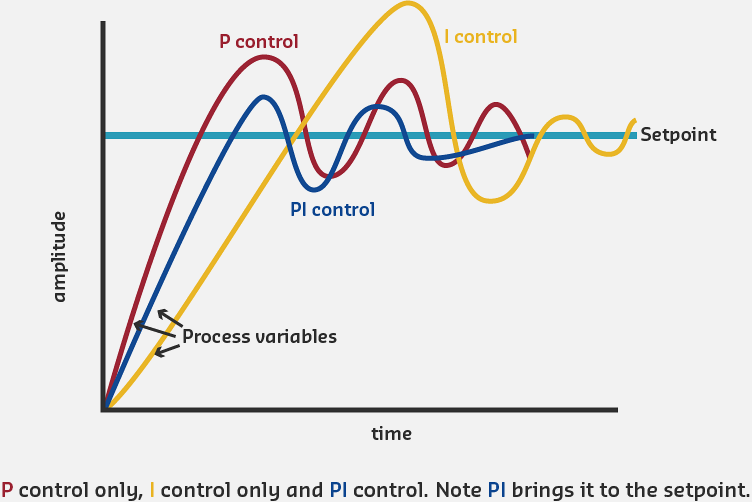

A PID controller uses three different control strategies simultaneously, each addressing different aspects of error correction:

- P (Proportional): Reacts to current error magnitude

- I (Integral): Reacts to accumulated error over time

- D (Derivative): Reacts to rate of error change

PID Controller Block Diagram: Error signal splits into three parallel paths. P term responds to current error, I term accumulates past errors, D term predicts future based on rate of change. All three combine to produce optimal control signal.

223.4 The PID Equation

\[ u(t) = K_p \cdot e(t) + K_i \cdot \int_{0}^{t} e(\tau) \, d\tau + K_d \cdot \frac{de(t)}{dt} \]

Where:

- \(u(t)\) = Controller output at time \(t\)

- \(e(t)\) = Error (Set Point - Process Variable)

- \(K_p\) = Proportional gain

- \(K_i\) = Integral gain

- \(K_d\) = Derivative gain

223.5 Understanding Error in PID Control

The foundation of PID control is the error signal:

- Process Variable (PV)

- The actual measured value of what we’re controlling (e.g., current temperature)

- Set Point (SP)

- The desired target value (e.g., target temperature)

- Error (e)

- The difference between desired and actual values

\[ e(t) = SP - PV(t) \]

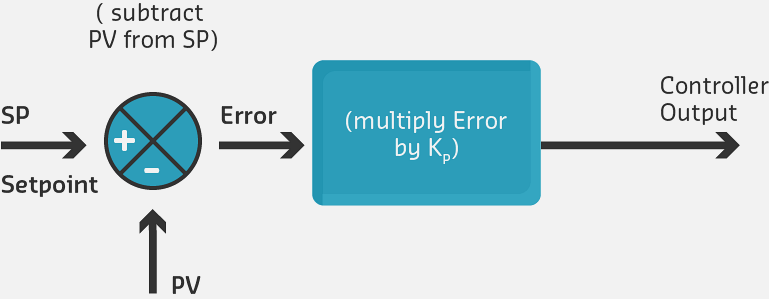

223.6 Proportional Control (P)

The Proportional term provides control action directly proportional to the current error. Larger errors produce stronger corrections.

\[ u_p(t) = K_p \cdot e(t) \]

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '16px'}}}%%

graph LR

Error["Error<br/>e(t)"] -->|Multiply by Kp| Gain["Proportional<br/>Gain<br/>Kp"]

Gain -->|Output = Kp x e(t)| Output["Control<br/>Output<br/>u_p(t)"]

Large["Large Error<br/>e = 5 deg C"] -.->|"Kp=2<br/>Output=10"| Strong["Strong<br/>Correction"]

Small["Small Error<br/>e = 0.5 deg C"] -.->|"Kp=2<br/>Output=1"| Weak["Weak<br/>Correction"]

style Error fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Gain fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style Output fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

Characteristics:

- Fast response: Immediate reaction to errors

- Simple implementation: Single multiplication

- Proportional output: Big errors produce big corrections; small errors produce small corrections

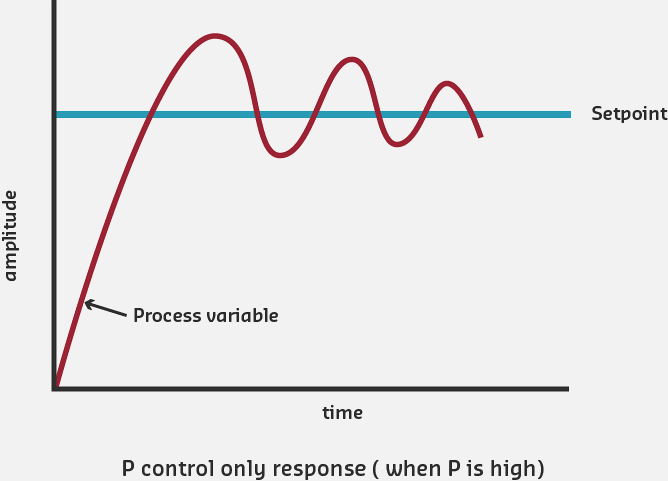

Problems with P-Only Control:

- Steady-State Error: System may never reach exact set point

- Overshoot: High Kp causes system to go past target

- Oscillation: High Kp can cause continuous cycling around set point

223.7 Integral Control (I)

The Integral term accumulates error over time and provides control action based on the total accumulated error. This eliminates steady-state error that P-only control cannot handle.

\[ u_i(t) = K_i \cdot \int_{0}^{t} e(\tau) \, d\tau \]

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '15px'}}}%%

graph TB

Error["Error<br/>e(t)"] -->|Accumulate<br/>Over Time| Int["Integral<br/>sum of e(t)"]

Int -->|Multiply by Ki| Gain["Integral<br/>Gain<br/>Ki"]

Gain -->|Output = Ki x integral| Output["Control<br/>Output<br/>u_i(t)"]

Persist["Persistent<br/>Small Error<br/>e = 0.5 deg C"] -.->|"Accumulates:<br/>0.5+0.5+0.5..."| Growing["Growing<br/>Integral<br/>Output"]

Growing -.->|"Increases Until<br/>Error = 0"| Zero["Zero<br/>Steady-State<br/>Error"]

style Error fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Int fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Gain fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Output fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Zero fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

How Integral Control Works:

- Accumulates error over time

- If error persists (even small error), integral grows

- Integral keeps increasing until error becomes zero

- Also called “automatic reset” - resets bias until error eliminated

Mathematical Intuition:

The integral accumulates (sums) all past errors:

Time | Error | Proportional | Integral Accumulated | Total Output

-----|-------|-------------|---------------------|-------------

0s | +3C | Kp×3 = 1.5 | 0 | 1.5

1s | +2C | Kp×2 = 1.0 | Ki×(3+2) = 0.5 | 1.5

2s | +1C | Kp×1 = 0.5 | Ki×(3+2+1) = 0.6 | 1.1

3s | +1C | Kp×1 = 0.5 | Ki×(3+2+1+1) = 0.7 | 1.2

4s | 0C | Kp×0 = 0 | Ki×(...) = 0.7 | 0.7

5s | 0C | Kp×0 = 0 | Ki×(...) = 0.7 | 0.7

Kp = 0.5, Ki = 0.1Key Observation: Even when P term drops to zero (error = 0), I term maintains output, compensating for disturbances.

Benefits of Adding Integral:

- Eliminates steady-state error: System reaches exact set point

- Compensates for disturbances: Overcomes constant external forces

- Automatic adjustment: No manual reset needed

223.8 Derivative Control (D)

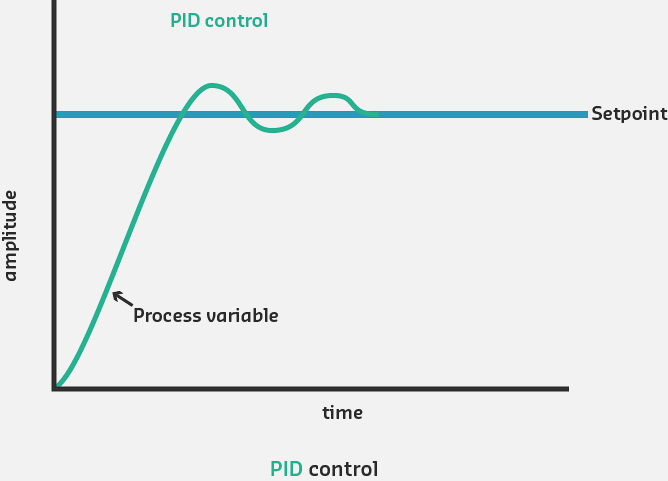

The Derivative term provides control action based on the rate of change of error. It anticipates future error trends and provides damping to prevent overshoot.

\[ u_d(t) = K_d \cdot \frac{de(t)}{dt} \]

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '15px'}}}%%

graph TB

Error["Error<br/>e(t)"] -->|Calculate Rate<br/>of Change| Deriv["Derivative<br/>de(t)/dt"]

Deriv -->|Multiply by Kd| Gain["Derivative<br/>Gain<br/>Kd"]

Gain -->|Output = Kd x de/dt| Output["Control<br/>Output<br/>u_d(t)"]

Fast["Error Decreasing<br/>Rapidly<br/>de/dt = -2 deg C/s"] -.->|Negative<br/>Derivative| Brake["Negative Output<br/>(Reduce Control)<br/>Prevents Overshoot"]

Slow["Error Stable<br/>de/dt = 0"] -.->|Zero<br/>Derivative| None["No D<br/>Contribution"]

style Error fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Deriv fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Gain fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Output fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Brake fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

How Derivative Control Works:

- Measures how fast error is changing: de/dt

- If error decreasing rapidly, derivative is negative

- Negative derivative reduces control action (anticipates reaching target)

- Provides damping effect to prevent overshoot

- Acts as predictive brake

Benefits of Adding Derivative:

- Reduces overshoot: Dampens aggressive P and I responses

- Improves stability: Prevents oscillations

- Faster settling: Reaches steady state more quickly

- Better response to changing conditions: Anticipates trends

Cautions with Derivative:

- Noise sensitivity: Amplifies high-frequency noise in sensor readings

- Difficult to tune: Kd selection is challenging

- Rarely used alone: Almost always combined with P and/or I

223.9 PID Configurations Comparison

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '14px'}}}%%

graph LR

subgraph POnly ["P-Only"]

P1["Fast<br/>Response"] --> P2["Steady-State<br/>Error<br/>Remains"]

end

subgraph PI ["PI Control"]

I1["Good<br/>Response"] --> I2["Zero<br/>Steady-State<br/>Error"]

I2 --> I3["Possible<br/>Overshoot"]

end

subgraph PID ["PID Control"]

D1["Fast<br/>Response"] --> D2["Zero<br/>Steady-State<br/>Error"]

D2 --> D3["Minimal<br/>Overshoot<br/>Best Performance"]

end

style P2 fill:#E74C3C,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style I3 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style D3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

PID Configuration Performance Comparison: P-only provides fast response but leaves steady-state error. PI eliminates error but may overshoot. Full PID combines fast response, zero error, and minimal overshoot.

| Mode | Usage | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| P | Sometimes | Simple temperature control, LED brightness |

| PI | Most common | HVAC systems, level control, pressure regulation |

| PID | Sometimes | Motor speed control, precision positioning |

| PD | Rare | Servo motors, fast response systems |

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D', 'fontSize': '12px'}}}%%

graph LR

subgraph Past["PAST (Integral Term)"]

direction TB

I_Desc["Remembers all<br/>previous errors"]

I_Calc["∫ e(τ) dτ"]

I_Benefit["Eliminates<br/>steady-state error"]

I_Risk["⚠️ Can cause<br/>overshoot if too high"]

end

subgraph Present["PRESENT (Proportional Term)"]

direction TB

P_Desc["Responds to<br/>current error"]

P_Calc["Kp × e(t)"]

P_Benefit["Immediate<br/>correction"]

P_Risk["⚠️ Cannot eliminate<br/>persistent error alone"]

end

subgraph Future["FUTURE (Derivative Term)"]

direction TB

D_Desc["Predicts based on<br/>rate of change"]

D_Calc["de/dt"]

D_Benefit["Prevents<br/>overshoot"]

D_Risk["⚠️ Sensitive to<br/>sensor noise"]

end

Past -->|"Ki ×"| Sum["Σ<br/>Combined<br/>Output"]

Present -->|"Kp ×"| Sum

Future -->|"Kd ×"| Sum

Sum --> Plant["System<br/>Response"]

style Past fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Present fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Future fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Sum fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

223.10 Knowledge Check

223.11 Summary

This chapter covered the theory of PID control:

- PID Equation: Combined P, I, and D terms with their respective gains

- Proportional (P): Responds to current error magnitude - fast but leaves steady-state error

- Integral (I): Accumulates past errors - eliminates steady-state error but can cause windup

- Derivative (D): Predicts future from rate of change - reduces overshoot but sensitive to noise

- Configuration Selection: P for simple systems, PI for most applications, full PID for precision control

223.12 What’s Next

The next chapter covers PID Tuning and Applications, including systematic tuning methods, real-world examples, and practical implementation considerations for IoT systems.

- Feedback Fundamentals - Foundation concepts

- Open-Loop and Closed-Loop Systems - Control architectures

- PID Tuning and Applications - Practical implementation

- Sensor Fundamentals - Feedback sensors

- Actuators - Control outputs