%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ECF0F1', 'fontFamily': 'Inter, system-ui, sans-serif'}}}%%

graph TD

SOURCE["Source Code"] --> COMPILER{"Compiler<br/>Optimization"}

COMPILER -->|"-O0"| O0["No Optimization<br/>Fast compile<br/>Easy debug<br/>Large/slow code"]

COMPILER -->|"-O1/-O2"| O2["Balanced<br/>Moderate compile<br/>Good performance<br/>Reasonable size"]

COMPILER -->|"-O3"| O3["Speed Focus<br/>Slow compile<br/>Aggressive inlining<br/>MASSIVE code size"]

COMPILER -->|"-Os"| OS["Size Focus<br/>Moderate compile<br/>Compact code<br/>Reduced performance"]

COMPILER -->|"-On"| ON["Custom Passes<br/>Fine control<br/>LLVM best<br/>Expert level"]

style SOURCE fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style O0 fill:#E74C3C,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style O2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style O3 fill:#F39C12,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style OS fill:#3498DB,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style ON fill:#9B59B6,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

1623 Software Optimization Techniques

1623.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Select appropriate compiler optimization flags: Choose between -O0, -O2, -O3, and -Os based on requirements

- Analyze code size considerations: Understand why flash memory dominates embedded system costs

- Apply SIMD vectorization: Exploit data-level parallelism for array processing

- Implement function inlining strategies: Balance call overhead against code size

- Design opportunistic sleeping patterns: Maximize battery life through intelligent power management

- Profile before optimizing: Use measurement to identify actual bottlenecks

1623.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- Optimization Fundamentals: Understanding optimization trade-offs and priorities

- Hardware Optimization: Understanding the hardware capabilities that software optimization leverages

- Embedded Systems Programming: Familiarity with embedded C/C++ programming

1623.3 Software Optimisation

1623.3.1 Compiler Optimisation Choices

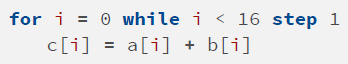

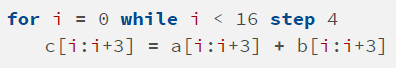

{fig-alt=“Compiler optimization level comparison showing trade-offs between -O0 (no optimization), -O1/-O2 (balanced), -O3 (speed-focused), -Os (size-focused), and -On (custom passes) in terms of compile time, code size, and performance”}

-O3 (Optimize for Speed): - May aggressively inline functions - Generates MASSIVE amounts of code - Re-orders instructions for better performance - Selects complex instruction encodings

-Os (Optimize for Size): - Penalizes inlining decisions - Generates shorter instruction encodings - Affects instruction scheduling - Fewer branches eliminated

-On (Custom Optimization): - Very specific optimization passes - Insert assembly language templates - LLVM is best for this

1623.3.2 Code Size Considerations

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ECF0F1', 'fontFamily': 'Inter, system-ui, sans-serif'}}}%%

graph LR

subgraph "Die Area Comparison @ 0.13um"

M3["ARM Cortex M3<br/>0.43 mm2"]

FLASH["128-Mbit Flash<br/>27.3 mm2"]

end

M3 -.->|"63x larger!"| FLASH

subgraph "Code Size Strategies"

DUAL["Dual Instruction Sets<br/>Thumb/Thumb-2<br/>16-bit + 32-bit"]

CISC["CISC Encodings<br/>x86, System/360<br/>Complex instructions"]

COMPRESS["Code Compression<br/>Decompress at runtime"]

end

FLASH --> DUAL

FLASH --> CISC

FLASH --> COMPRESS

style M3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style FLASH fill:#E74C3C,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style DUAL fill:#3498DB,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style CISC fill:#3498DB,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style COMPRESS fill:#3498DB,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

{fig-alt=“Code size impact diagram showing flash memory dominating die area (27.3mm2 vs 0.43mm2 for ARM Cortex M3) and three code size reduction strategies: dual instruction sets, CISC encodings, and code compression”}

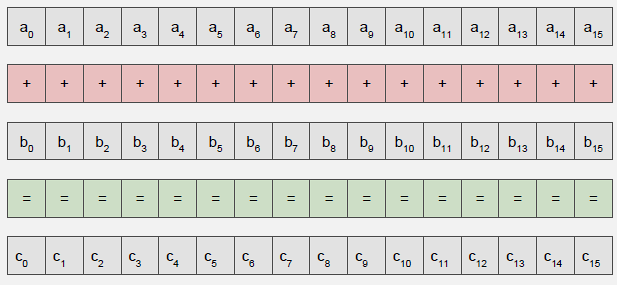

Does code size matter? - 128-Mbit Flash = 27.3 mm2 @ 0.13um - ARM Cortex M3 = 0.43 mm2 @ 0.13um - Flash memory can dominate die area!

Dual Instruction Sets: Thumb/Thumb-2, ARCompact, microMIPS - 16-bit instructions have constraints (limited registers, reduced immediates)

CISC Instruction Sets: x86, System/360, PDP-11 - Complex encodings do more work - Require more complex hardware - Compiler support may be limited

1623.4 Advanced Software Optimizations

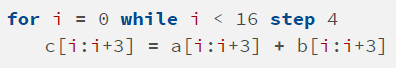

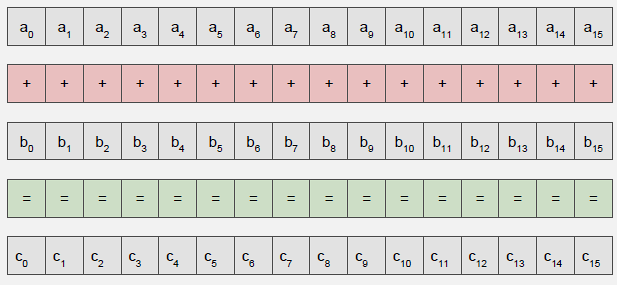

1623.4.1 Vectorization

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ECF0F1', 'fontFamily': 'Inter, system-ui, sans-serif'}}}%%

sequenceDiagram

participant Code as Source Code

participant Scalar as Scalar Execution<br/>(1 element/instruction)

participant SIMD as SIMD Vectorization<br/>(4 elements/instruction)

Note over Code: for i = 0 to 999<br/> array[i] = array[i] x 2

rect rgb(231, 76, 60, 0.1)

Note over Scalar: 1000 iterations

loop 1000 times

Scalar->>Scalar: Load 1 element

Scalar->>Scalar: Multiply by 2

Scalar->>Scalar: Store 1 element

end

end

rect rgb(22, 160, 133, 0.1)

Note over SIMD: 250 iterations (4x faster!)

loop 250 times

SIMD->>SIMD: Load 4 elements

SIMD->>SIMD: Multiply 4x2 (parallel)

SIMD->>SIMD: Store 4 elements

end

end

Note over SIMD: Data-level parallelism<br/>Better memory bandwidth<br/>Fewer loop iterations

{fig-alt=“SIMD vectorization comparison showing scalar execution processing one element per iteration requiring 1000 iterations versus SIMD processing four elements per instruction requiring only 250 iterations for 4x speedup”}

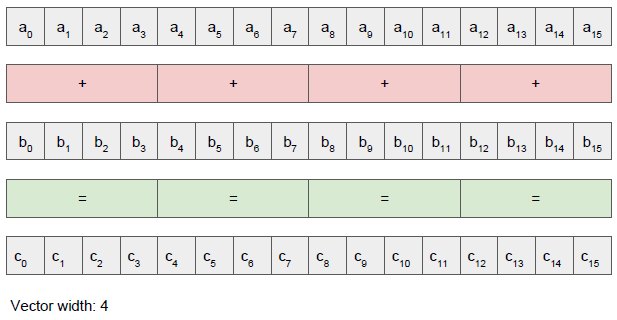

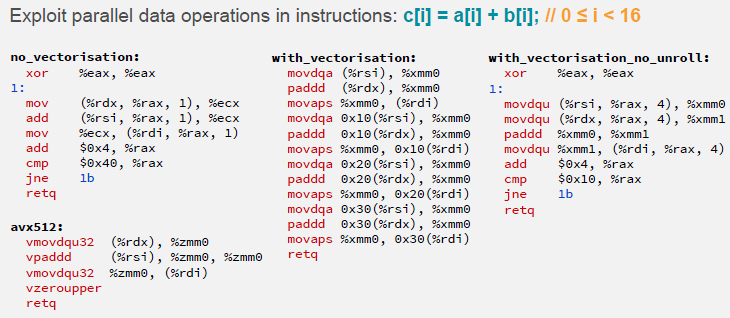

Key Idea: Operate on multiple data elements with single instruction (SIMD)

Benefits: - Fewer loop iterations - Better memory bandwidth utilization - Exploits data-level parallelism

Caution: Need extra code if vector width doesn’t divide iteration count exactly!

1623.4.2 Function Inlining

Advantages: - Low calling overhead - Avoids branch delay - Enables further optimizations

Limitations: - Not all functions can be inlined - Code size explosion possible - May require manual intervention (inline qualifier)

Function inlining eliminates call overhead but increases code size, requiring careful analysis of which functions benefit from this optimization.

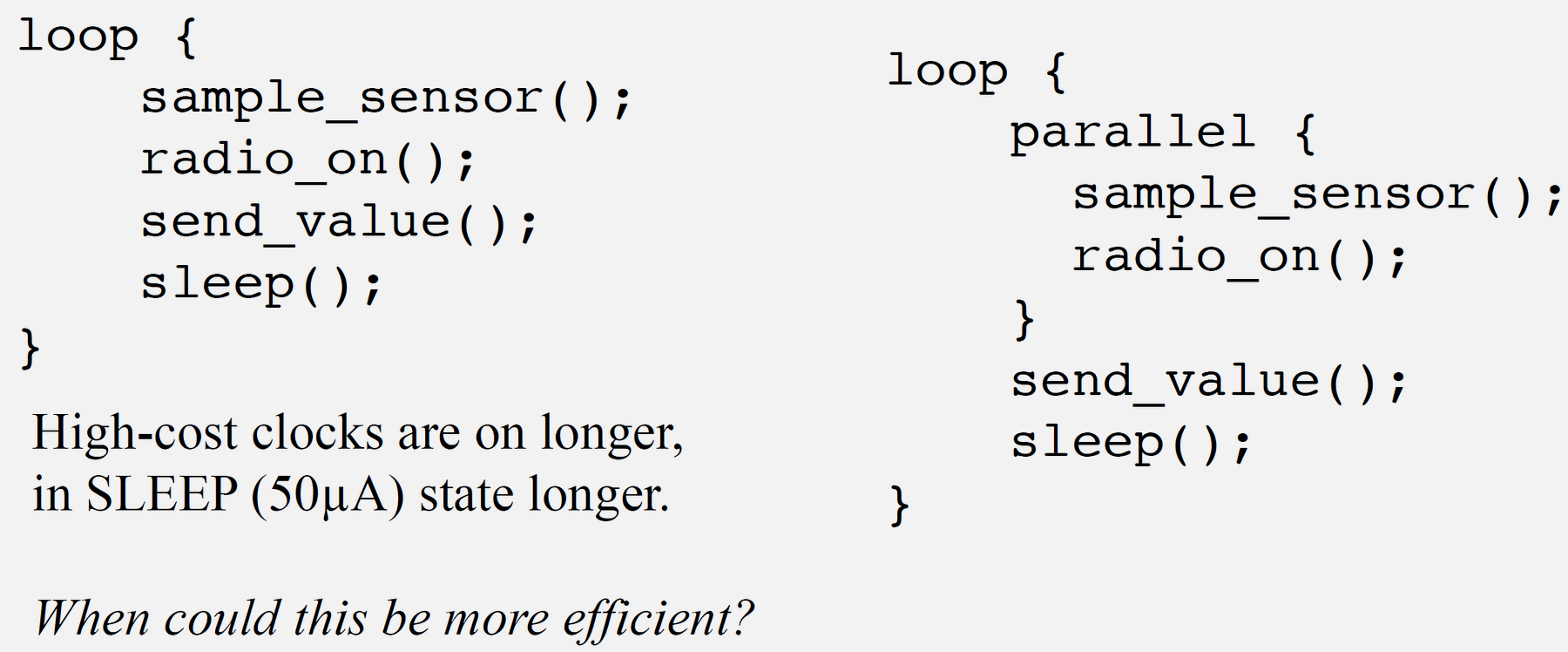

1623.4.3 Opportunistic Sleeping

Strategy: Transition processor and peripherals to lowest usable power mode ASAP

- Similar to stop/start in cars!

- Interrupts wake the processor for processing

- Balance energy savings vs reaction time

1623.5 Knowledge Check

The Mistake: Adding Serial.print() or printf() statements inside tight loops or ISRs to debug timing-sensitive code, then wondering why the bug disappears when debug output is added, or why the system becomes unreliable during debugging.

Why It Happens: Serial output is extremely slow compared to CPU operations. A single Serial.print("x") on Arduino at 115200 baud takes approximately 87 microseconds (10 bits per character at 115200 bps). In a 1 MHz loop (1 us per iteration), adding one print statement slows execution by 87x and changes all timing relationships. This creates “Heisenbugs” - bugs that disappear when you try to observe them.

The Fix: Use GPIO pin toggling for timing-critical debugging - set a pin HIGH at function entry, LOW at exit, and observe with an oscilloscope or logic analyzer. For capturing values without affecting timing, write to a circular buffer in RAM and dump after the critical section completes:

// WRONG: Serial output changes timing

void IRAM_ATTR timerISR() {

Serial.println(micros()); // Takes 500+ us, destroys timing!

processData();

}

// CORRECT: GPIO toggle for timing debug (oscilloscope required)

#define DEBUG_PIN 2

void IRAM_ATTR timerISR() {

digitalWrite(DEBUG_PIN, HIGH); // ~0.1 us

processData();

digitalWrite(DEBUG_PIN, LOW); // ~0.1 us

}

// CORRECT: Buffer capture for value debug

volatile uint32_t debugBuffer[64];

volatile uint8_t debugIndex = 0;

void IRAM_ATTR timerISR() {

if (debugIndex < 64) {

debugBuffer[debugIndex++] = ADC_VALUE; // ~0.2 us

}

processData();

}

// Dump buffer in loop() after critical operation completesThe Mistake: Spending hours hand-optimizing a function that “looks slow” (like a nested loop or floating-point math) without measuring whether it actually impacts overall system performance, while ignoring the true bottleneck.

Why It Happens: Developers have intuitions about what should be slow based on algorithm complexity or “expensive” operations. But modern compilers optimize heavily, and I/O operations (network, storage, peripherals) often dominate execution time. A function with O(n^2) complexity processing 10 items (100 operations) may take 1 microsecond, while a single I2C sensor read takes 500 microseconds.

The Fix: Always profile before optimizing. On ESP32, use micros() to measure elapsed time. On ARM Cortex-M, use the DWT cycle counter (enabled via CoreDebug register). Identify the actual hotspot before optimizing:

// Step 1: Instrument code to find actual bottleneck

void loop() {

uint32_t t0 = micros();

readSensors(); // Suspect this is slow

uint32_t t1 = micros();

processData(); // Spent 2 weeks optimizing this

uint32_t t2 = micros();

transmitData(); // Never measured

uint32_t t3 = micros();

Serial.printf("Read: %lu us, Process: %lu us, Transmit: %lu us\n",

t1-t0, t2-t1, t3-t2);

}

// Typical result: Read: 2000 us, Process: 50 us, Transmit: 150000 us

// The "optimized" processData() was 0.03% of total time!

// Real fix: Reduce transmission frequency or payload size

// For ARM Cortex-M cycle-accurate profiling:

CoreDebug->DEMCR |= CoreDebug_DEMCR_TRCENA_Msk; // Enable trace

DWT->CYCCNT = 0; // Reset counter

DWT->CTRL |= DWT_CTRL_CYCCNTENA_Msk; // Start counting

// ... code to measure ...

uint32_t cycles = DWT->CYCCNT; // Read cyclesRule of thumb: 80% of execution time comes from 20% of code. Find the 20% first.

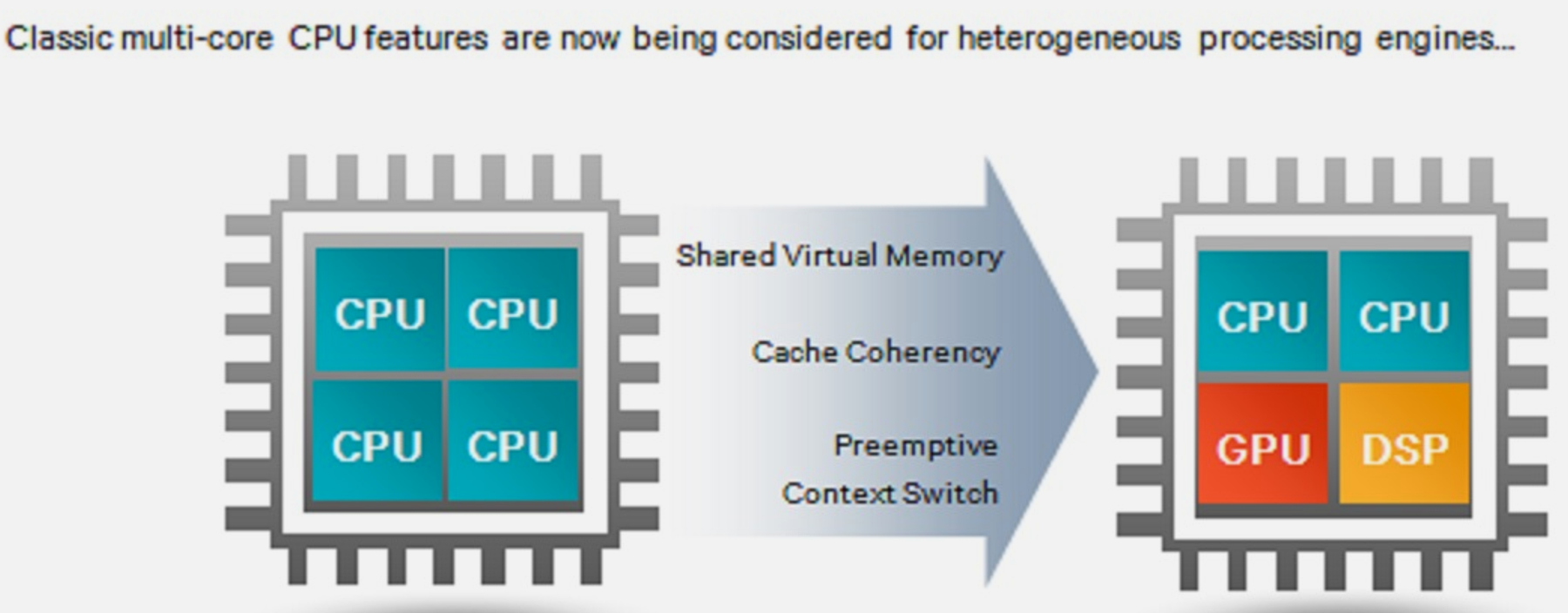

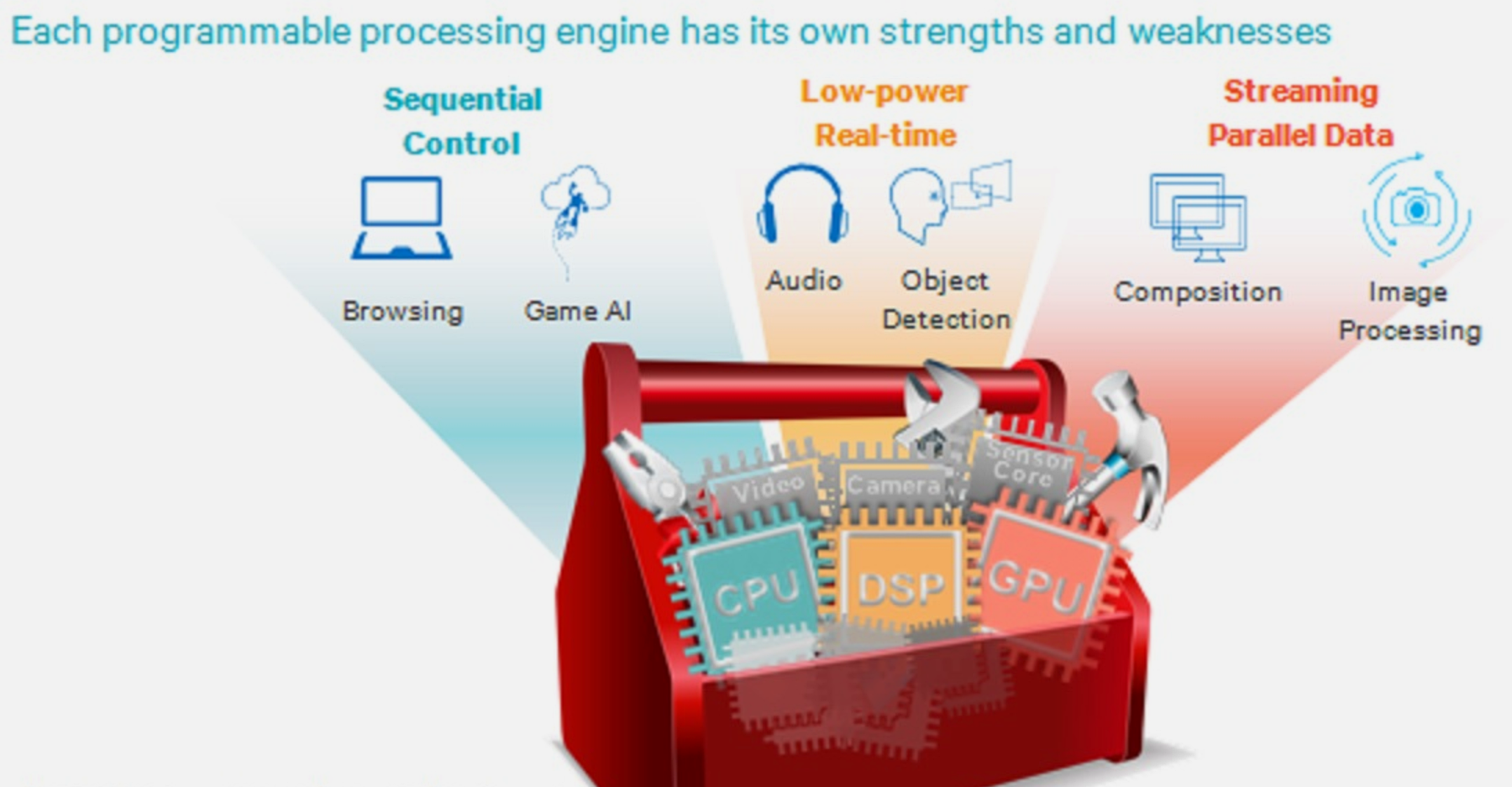

1623.6 Visual Reference Gallery

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 8 - Design and Prototyping

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 8 - Design and Prototyping

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 8 - Design and Prototyping

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 8 - Design and Prototyping

1623.7 Summary

Software optimization techniques are essential for efficient IoT firmware:

- Compiler Flags: -O3 for speed (large code), -Os for size (compact), -O2 for balance

- Code Size Matters: Flash memory dominates die area (27.3 mm2 vs 0.43 mm2 for CPU)

- Dual Instruction Sets: Thumb/Thumb-2 provide 30% code size reduction

- Vectorization (SIMD): Process 4+ elements per instruction for 4x+ speedup

- Function Inlining: Reduces call overhead but increases code size

- Opportunistic Sleeping: Transition to low-power modes ASAP

- Profile First: Measure actual bottlenecks before optimizing

The key is applying the right technique to the measured bottleneck, not optimizing based on assumptions.

1623.8 What’s Next

The next chapter covers Fixed-Point Arithmetic, which explores Qn.m format representation, conversion from floating-point, and efficient implementation on embedded processors without floating-point hardware.