%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph PACKET["Complete Network Packet (Variable Size)"]

direction TB

subgraph HEADER["HEADER SECTION (10-40 bytes)"]

H1["Source Address<br/>4-16 bytes"]

H2["Destination Address<br/>4-16 bytes"]

H3["Length Field<br/>2 bytes"]

H4["Protocol/Type<br/>1-2 bytes"]

H5["Sequence #<br/>2-4 bytes"]

H6["Flags/Options<br/>1-4 bytes"]

end

subgraph PAYLOAD["PAYLOAD SECTION (0-MTU bytes)"]

P1["Application Data<br/>Sensor readings, JSON,<br/>commands, or nested packet"]

end

subgraph TRAILER["TRAILER SECTION (2-4 bytes)"]

T1["CRC/Checksum<br/>Error detection"]

T2["End Marker<br/>Optional delimiter"]

end

end

H1 --> H2 --> H3 --> H4 --> H5 --> H6

H6 --> P1

P1 --> T1 --> T2

style HEADER fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style PAYLOAD fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style TRAILER fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style H1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style H2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style H3 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style H4 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style H5 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style H6 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style P1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style T1 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style T2 fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style PACKET fill:#ecf0f1,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px

50 Packet Anatomy: Headers, Payloads, and Trailers

50.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand packet anatomy: Identify headers, payloads, and trailers in network packets

- Read protocol specifications: Interpret frame format diagrams in datasheets

- Recognize packet components: Distinguish control information from actual data

Prerequisites (Read These First): - Data Representation - Binary, hexadecimal, and bitwise operations for parsing packet fields

Companion Chapters (Packet Structure Series): - Packet Structure Overview - Index of all packet structure topics - Frame Delimiters and Boundaries - How receivers detect packet boundaries - Error Detection - Checksums, CRC, and data integrity - Protocol Overhead - Header comparison and encapsulation

Fundamentals (Core Concepts): - Data Formats for IoT - Payload encoding (JSON, CBOR, Protocol Buffers) - Sensor to Network Pipeline - How sensor data becomes network packets

Protocol-Specific Packet Structures: - MQTT - MQTT fixed/variable headers, QoS, and packet types - CoAP - CoAP 4-byte header and message format - LoRaWAN - LoRa MAC header (MHDR), DevAddr, FCnt, MIC

50.2 Prerequisites

Before this chapter, you should understand:

- Data Representation Fundamentals: Binary, hexadecimal, and bitwise operations for parsing packet fields

50.3 For Beginners: Why Packet Structure Matters

Analogy: Packets are like Postal Letters

Just like a letter has a standard structure, network packets have a predictable format:

- Header (envelope) - return address, destination address, and stamp tell the postal system where to send the letter and who sent it.

- Payload (letter body) - the actual message you write to your friend.

- Trailer (signature) - a final check such as a signature that lets the recipient verify it really came from you.

Network Packet:

The same idea appears in networking:

| Part | What it contains | Typical size |

|---|---|---|

| Header | Source/destination, length, type, sequence number, flags | 10-40 bytes |

| Payload | Sensor reading, command, JSON message, or even another packet | Variable |

| Trailer | Checksum/CRC, end marker, optional padding | 2-4 bytes |

Why does this structure exist?

- Routing: Headers tell devices where to send the packet

- Integrity: Trailers verify data wasn’t corrupted

- Multiplexing: Multiple conversations share the same wire

- Reassembly: Large messages split into smaller packets

Key Terms:

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Packet | Complete unit of data for transmission |

| Frame | Packet at the data link layer (includes physical markers) |

| Header | Metadata at the beginning (addresses, length, type) |

| Payload | Actual data being transmitted |

| Trailer | Metadata at the end (error checking) |

| Checksum | Simple error detection value |

| CRC | Cyclic Redundancy Check - more robust error detection |

| MTU | Maximum Transmission Unit - largest packet size allowed |

Let’s dissect a real LoRaWAN packet from a temperature sensor deployed in a smart building. This packet was captured using a LoRaWAN gateway during an actual transmission:

Raw Packet (Hexadecimal):

40 3A 2B 1C 0D 80 02 00 01 C8 49 E2 F4 A3 B7 82 1FBreaking it down:

| Field | Bytes | Hex Value | Decoded Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHDR | 1 | 40 |

Message Type: Unconfirmed Data Up | Indicates packet type and direction |

| DevAddr | 4 | 3A 2B 1C 0D |

Device Address: 0x0D1C2B3A | Unique 32-bit device identifier |

| FCtrl | 1 | 80 |

Frame Control: ADR enabled | Controls adaptive data rate and options |

| FCnt | 2 | 02 00 |

Frame Counter: 2 | Prevents replay attacks (increments each transmission) |

| FPort | 1 | 01 |

Port 1 | Application port number |

| Payload | 2 | C8 49 |

Temperature: 22.5C | Actual sensor data (0x49C8 = 18888 -> 18888/840 = 22.5C) |

| MIC | 4 | E2 F4 A3 B7 |

Message Integrity Code | CRC-like authentication tag |

| Extra | 2 | 82 1F |

Gateway metadata | Added by gateway (RSSI, SNR) |

Total: 17 bytes (13 header + 2 payload + 4 MIC) = 88% overhead for just 2 bytes of temperature data!

Key Insights: - DevAddr routes the packet to the correct application server - FCnt prevents attackers from replaying old packets - MIC uses AES-128-CMAC to verify packet authenticity and integrity - Small payload (2 bytes) means high overhead ratio, but LoRaWAN optimizes for range (10+ km) and battery life (10+ years) - Gateway adds metadata (RSSI, SNR) to help with diagnostics

Why is this structure important? - Parsing this packet requires reading the LoRaWAN specification to understand each field - Frame counter must increment or the network server rejects the packet (anti-replay protection) - Payload encoding (0x49C8 -> 22.5C) is application-specific and not part of the LoRaWAN spec - Understanding packet structure helps debug connectivity issues with tools like Wireshark or TTN Console

50.4 Generic Packet Anatomy

50.4.1 The Three Parts of Every Packet

Every network packet, regardless of protocol, contains these fundamental components:

1. Header (Control Information) - Purpose: Routing, identification, and control - Contains: Source/destination addresses, packet length, protocol type, sequence numbers, flags - Size: Typically 10-40 bytes depending on protocol

2. Payload (The Actual Data) - Purpose: Carry the message or data being transmitted - Contains: Sensor readings, commands, JSON data, or another encapsulated packet - Size: Variable, constrained by Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU)

3. Trailer (Error Detection) - Purpose: Verify data integrity - Contains: Checksum or CRC value, optional end-of-frame marker - Size: Typically 2-4 bytes

Alternative View:

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph POSTAL["Postal Letter Analogy"]

ENV["<b>Envelope</b><br/>━━━━━━━━<br/>From: Sensor-001<br/>To: Cloud Server<br/>Stamp: Priority<br/>━━━━━━━━<br/>Like: HEADER"]

LETTER["<b>Letter Content</b><br/>━━━━━━━━<br/>Temperature: 23.5C<br/>Humidity: 65%<br/>Battery: 3.2V<br/>━━━━━━━━<br/>Like: PAYLOAD"]

SEAL["<b>Wax Seal</b><br/>━━━━━━━━<br/>Signature verifies<br/>letter is authentic<br/>and unchanged<br/>━━━━━━━━<br/>Like: TRAILER/CRC"]

end

subgraph NETWORK["Network Packet"]

HEADER["<b>Header</b><br/>Source IP, Dest IP<br/>Length, Protocol<br/>Sequence number"]

PAYLOAD["<b>Payload</b><br/>Sensor readings<br/>JSON/CBOR data<br/>Commands"]

TRAILER["<b>Trailer</b><br/>CRC checksum<br/>Error detection<br/>Authentication"]

end

ENV -.->|"Same purpose"| HEADER

LETTER -.->|"Same purpose"| PAYLOAD

SEAL -.->|"Same purpose"| TRAILER

style ENV fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style LETTER fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style SEAL fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style HEADER fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style PAYLOAD fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

style TRAILER fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

This chapter connects to multiple learning resources across the IoT Class platform:

Interactive Learning: - Simulations Hub: Analyze real packets with Wireshark tutorials, packet dissection tools, and protocol analyzers - Knowledge Map: See how packet structure fits into the networking stack and protocol design - Quizzes Hub: Test your understanding of framing, error detection, and header parsing - Videos Hub: Watch step-by-step packet dissection demonstrations and protocol analysis

Hands-On Activities: - Network Traffic Analysis: Use Wireshark to capture and analyze packets from your own IoT devices - Protocol Simulators: Build your own packet structures and test framing techniques - Error Detection Calculator: Compute checksums and CRC values for practice packets - Header Comparison Tool: Compare overhead across different IoT protocols

Deep Dives: - Explore protocol-specific packet structures in MQTT, CoAP, and LoRaWAN - Learn how packets flow through the network stack in Layered Models - Understand packet encapsulation in Sensor to Network Pipeline

50.5 Visual Reference Gallery

The following figures provide alternative visual perspectives on packet structure concepts covered in this chapter.

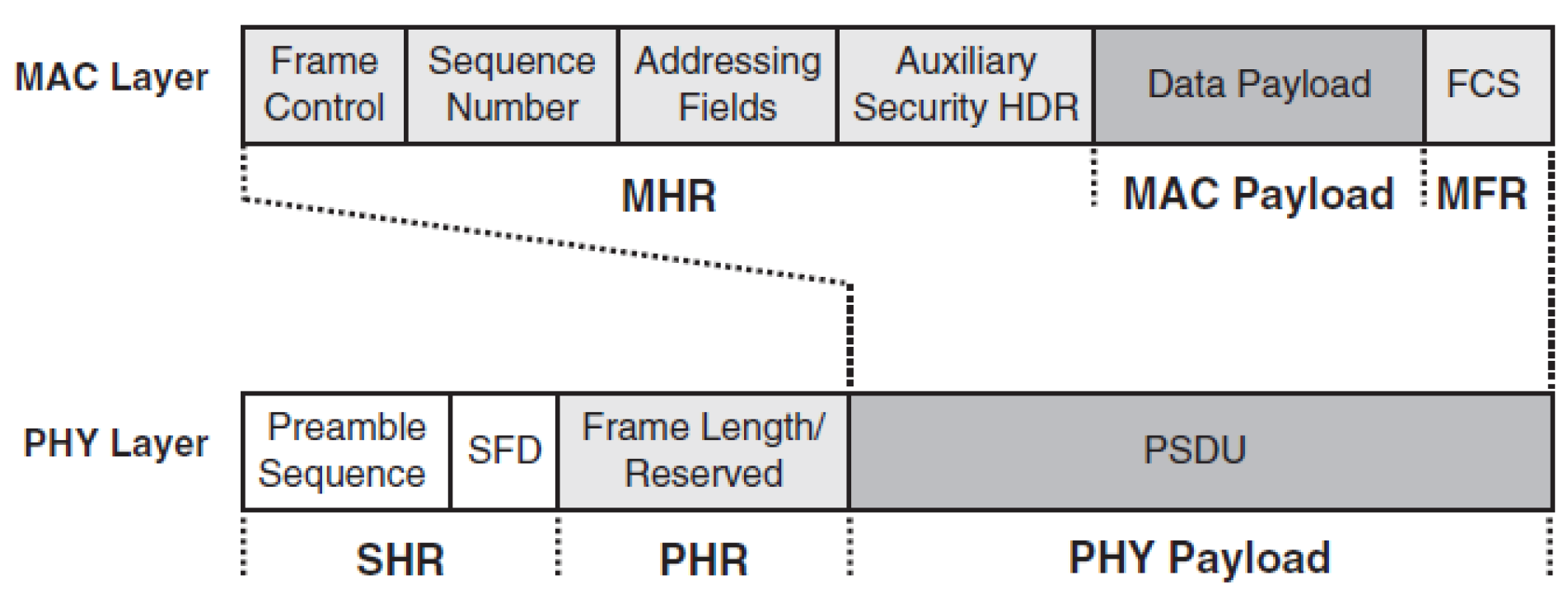

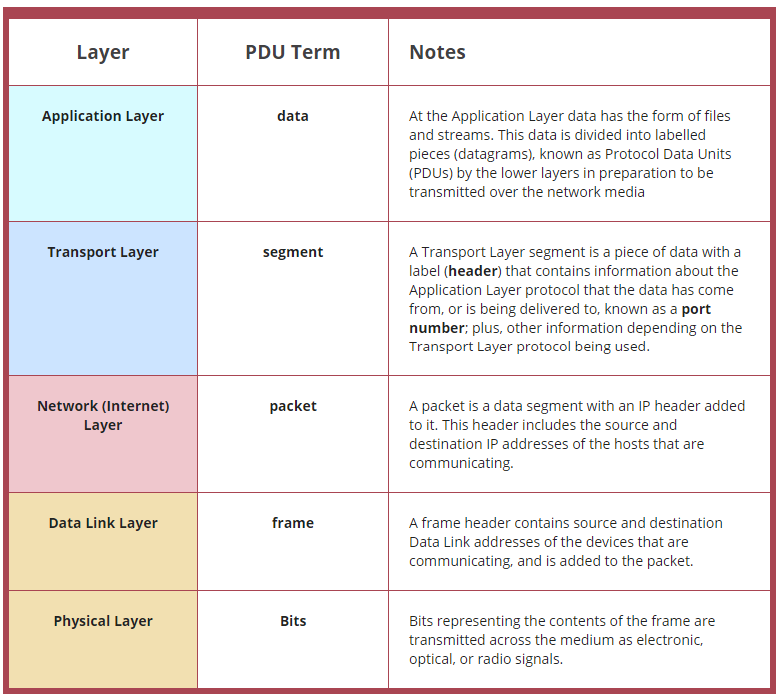

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 4 - Networking Fundamentals

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 4 - Networking Fundamentals

A data frame is the complete package that travels across network links. This visualization breaks down the key components: the preamble for synchronization, header fields containing addressing and control information, the payload carrying actual data, and the trailer with Frame Check Sequence (FCS) for error detection. Understanding frame structure helps engineers calculate overhead ratios and select appropriate protocols for bandwidth-constrained IoT deployments.

50.6 Summary

Packet anatomy is the foundation of all network communication:

- Three Parts: Every packet contains Header (routing/control), Payload (data), and Trailer (error checking)

- Header Fields: Source/destination addresses, length, type, sequence numbers, and flags

- Payload: Variable-size section carrying actual sensor data or application messages

- Trailer: Error detection using checksums or CRC values

Key Takeaways: - Headers provide metadata needed for routing and protocol operation - Payload size is limited by the Maximum Transmission Unit (MTU) - Understanding packet structure is essential for debugging with tools like Wireshark

50.7 What’s Next

Continue exploring packet structure with these related chapters:

- Frame Delimiters and Boundaries - How receivers detect where packets begin and end

- Error Detection - Checksums, CRC, and ensuring data integrity

- Protocol Overhead - Comparing header sizes and encapsulation