215 Processes & Systems: PID Control

215.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Apply PID Control: Understand proportional, integral, and derivative control components

- Design Stable Systems: Evaluate trade-offs between different control strategies for IoT

- Tune PID Controllers: Find optimal gain values for system performance

- Implement Control Algorithms: Write PID control code for IoT devices

- Select Control Strategies: Choose appropriate methods based on system requirements

215.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- Processes & Systems: Core Definitions: Understanding system decomposition and input-output transformations

- Processes & Systems: Control Types: Open-loop vs closed-loop control and feedback mechanisms

- Sensor Fundamentals and Types: How sensors measure physical phenomena for feedback

- Actuators: How actuators produce physical outputs in response to control signals

215.3 Getting Started (For Beginners)

TipWhat is PID Control? (Simple Explanation)

Analogy: PID control is like driving a car to a target speed:

- P (Proportional): The farther you are from target speed, the harder you press the gas

- I (Integral): If you’ve been slow for a while, press harder to catch up

- D (Derivative): If you’re approaching target fast, ease off to avoid overshooting

Combined: P + I + D = smooth, accurate approach to your target!

NoteKey Takeaway

In one sentence: PID combines three control actions—react to current error (P), eliminate persistent offset (I), and dampen oscillations (D)—to maintain precise setpoint control.

Remember this: Most real-world control systems (thermostats, drones, cruise control) use PID because it handles disturbances and changes automatically.

215.4 PID Control Basics for IoT

⭐⭐ Difficulty: Intermediate

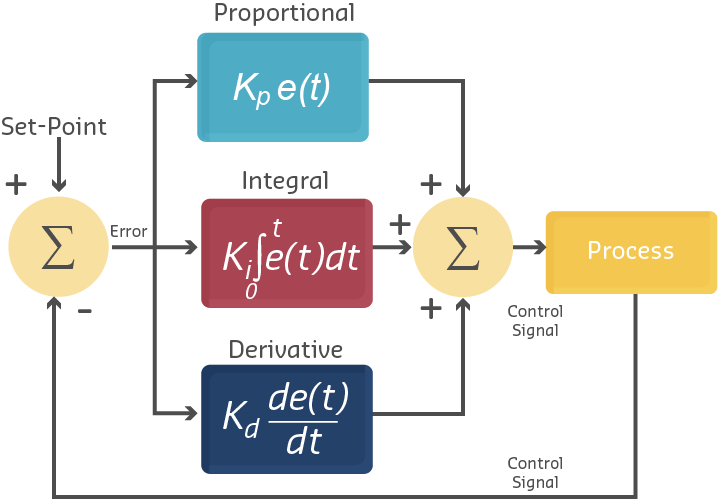

Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control is the most widely used feedback control algorithm in industrial automation and IoT systems. It combines three control actions to maintain a system at its desired setpoint.

215.4.1 The PID Formula

The PID controller calculates the control output \(u(t)\) based on the error \(e(t)\) between the setpoint and the measured value:

\[ u(t) = K_p \cdot e(t) + K_i \cdot \int_0^t e(\tau) \, d\tau + K_d \cdot \frac{de(t)}{dt} \]

Where: - \(u(t)\): Control output (e.g., valve position, motor speed, heater power) - \(e(t) = \text{setpoint} - \text{measured value}\): Current error - \(K_p\): Proportional gain (how strongly to react to current error) - \(K_i\): Integral gain (how strongly to correct accumulated past errors) - \(K_d\): Derivative gain (how strongly to react to error rate of change)

215.4.2 The Three Control Actions

1. Proportional (P) - React to Current Error:

- What it does: Output is proportional to the current error magnitude

- Effect: Larger error → stronger correction

- Problem: Never quite reaches setpoint (steady-state error)

- Analogy: Pushing harder on accelerator the farther you are from target speed

Example: Smart thermostat with P-only control: - Current temp: 18°C, Setpoint: 22°C → Error: 4°C - Control output: \(u = K_p \times 4\) (e.g., if \(K_p = 15\), then \(u = 60\%\) heater power) - As room warms to 21°C, error drops to 1°C → \(u = 15\%\) heater power - Problem: At 21.7°C, heater power equals heat loss → stuck below setpoint!

2. Integral (I) - Account for Accumulated Error:

- What it does: Accumulates error over time and corrects for persistent offset

- Effect: Eliminates steady-state error (eventually reaches exact setpoint)

- Problem: Can cause overshoot and slow oscillations if too aggressive

- Analogy: Remembering that you’ve been consistently behind schedule and compensating

Example: Adding I-control to thermostat: - Even when temp hovers at 21.7°C (error = 0.3°C), integral term keeps growing - \(\int e(t) dt\) accumulates: 0.3 + 0.3 + 0.3… over many time steps - Eventually integral term adds enough output to push temp to exactly 22°C - Benefit: Reaches exact setpoint, not just “close enough”

3. Derivative (D) - Predict Future Error:

- What it does: Responds to rate of change of error (how fast it’s changing)

- Effect: Dampens oscillations, improves stability, slows overshoot

- Problem: Amplifies sensor noise (small noise fluctuations look like large rate changes)

- Analogy: Seeing you’re approaching target speed quickly and easing off accelerator early

Example: Adding D-control to thermostat: - Temp rising rapidly from 18°C → 19°C → 20°C (1°C per minute) - \(de/dt = -1°C/\text{min}\) (error decreasing at 1°C/min) - D-term reduces output before reaching setpoint: “We’re getting there fast—slow down!” - Benefit: Less overshoot, smoother approach to setpoint

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

sequenceDiagram

participant SP as Setpoint<br/>22.0 C

participant CTRL as PID Controller

participant HVAC as HVAC System

participant ROOM as Clean Room

participant SENS as Temp Sensor

Note over SP,SENS: t=0s: Initial state - Room at 20.0 C

SP->>CTRL: Target: 22.0 C

SENS->>CTRL: Measured: 20.0 C

Note over CTRL: Error = +2.0 C<br/>P=70%, I accumulating, D=0

CTRL->>HVAC: Output: 70% heating

HVAC->>ROOM: Heat input HIGH

Note over SP,SENS: t=60s: Room warming

SENS->>CTRL: Measured: 21.2 C

Note over CTRL: Error = +0.8 C<br/>P=28%, I growing, D negative

CTRL->>HVAC: Output: 35% heating

Note over CTRL: D-term reduces output<br/>anticipating approach

Note over SP,SENS: t=120s: Near setpoint

SENS->>CTRL: Measured: 21.9 C

Note over CTRL: Error = +0.1 C<br/>P=3%, I eliminates offset, D braking

CTRL->>HVAC: Output: 12% heating

HVAC->>ROOM: Maintain steady state

Note over SP,SENS: t=180s: Stable at 22.0 C +/- 0.08 C

215.4.3 Tuning PID Controllers

Finding the right \(K_p\), \(K_i\), \(K_d\) values is critical:

| Parameter | Too Low | Optimal | Too High |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(K_p\) (Proportional) | Slow response, large steady-state error | Fast response, minimal overshoot | Overshoot, oscillations, instability |

| \(K_i\) (Integral) | Persistent offset, never reaches setpoint | Eliminates offset, stable | Large overshoot, slow oscillations |

| \(K_d\) (Derivative) | Overshoot, oscillations | Smooth approach, damped response | Noise amplification, erratic behavior |

Common Tuning Methods:

- Ziegler-Nichols Method: Empirical tuning based on step response

- Manual Tuning: Start with P-only, add I to eliminate offset, add D to reduce overshoot

- Auto-Tuning: Modern controllers can self-tune by observing system response

215.5 Real IoT PID Control Examples

215.5.1 Example 1: Smart Thermostat (Temperature Control)

System Components:

| Component | Details | IoT Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Setpoint | Desired temperature: 22°C | Set via smartphone app or voice assistant |

| Sensor | DHT22 temperature sensor (±0.5°C) | I2C interface to ESP32 microcontroller |

| Controller | PID algorithm (\(K_p=15\), \(K_i=0.5\), \(K_d=5\)) | Runs every 30 seconds on ESP32 |

| Actuator | Smart relay controlling HVAC system | 240V relay switched by GPIO pin |

| Process | Room thermal dynamics (5-10 min time constant) | Cloud logging of temperature history |

Operation:

1. Measure: Sensor reads 18.5°C

2. Error: 22.0 - 18.5 = 3.5°C

3. P-term: 15 × 3.5 = 52.5

4. I-term: 0.5 × Σ(errors) = 0.5 × 12.3 = 6.15 (accumulated over past 5 minutes)

5. D-term: 5 × (3.5 - 3.8)/30s = -0.05 (error decreasing slowly)

6. Output: 52.5 + 6.15 - 0.05 = 58.6% heater duty cycle

7. Actuate: HVAC runs at 58.6% power for next 30 seconds

8. Repeat: Measure again after 30 secondsResults: - Settling Time: 8 minutes to reach 22°C ±0.2°C - Overshoot: <0.3°C (minimal temperature overshoot) - Energy Savings: 23% reduction vs simple on/off thermostat - Comfort: ±0.2°C stability vs ±1.5°C with on/off control

215.5.2 Example 2: Drone Stability (Orientation Control)

System Components:

| Component | Details | Update Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Setpoint | Target orientation: level (0° pitch, 0° roll) | User joystick commands |

| Sensor | MPU-6050 IMU (gyroscope + accelerometer) | 100 Hz (every 10ms) |

| Controller | Cascaded PID loops (angle PID → rate PID) | 400 Hz (every 2.5ms) |

| Actuator | 4× brushless motors with ESCs | PWM 1000-2000µs pulse width |

| Process | Quadcopter rotational dynamics | <50ms response time |

Dual-Loop Control (Cascaded PID):

Outer Loop (Angle Control): - Setpoint: 0° pitch (level flight) - Measured: Accelerometer reads 5° nose-down pitch - Error: 0° - 5° = -5° - PID Output: Desired pitch rate = +30°/sec (rotate nose up)

Inner Loop (Rate Control): - Setpoint: +30°/sec (from outer loop) - Measured: Gyroscope reads +10°/sec (rotating up, but too slowly) - Error: +30°/sec - 10°/sec = +20°/sec - PID Output: Increase rear motors by 15%, decrease front motors by 15% - Result: Drone pitches nose up at 30°/sec → returns to level

Why Two Loops? - Outer loop (slow): Strategic goal—“Get to level orientation” - Inner loop (fast): Tactical execution—“Rotate at this exact rate” - Benefit: Faster response, better stability than single-loop control

215.5.3 Example 3: Water Tank Level Control

System Setup:

| Component | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Setpoint | 75% tank level | Maintain optimal water supply |

| Sensor | Ultrasonic distance sensor (HC-SR04, ±3mm) | Measure water level every 5 seconds |

| Controller | Arduino Uno running PID library | Calculate pump speed (0-100%) |

| Actuator | Variable speed pump (0-50 liters/min) | Controlled via PWM to motor driver |

| Process | 1000-liter water tank (60cm × 60cm × 278cm) | 5-minute time constant |

Control Challenges:

- Disturbances: Water consumption varies (0-30 L/min depending on household usage)

- Nonlinearity: Pump efficiency changes with tank level (less efficient at low levels)

- Noise: Ultrasonic sensor has ±3mm noise (~0.3% of tank height)

PID Solution (\(K_p=20\), \(K_i=0.8\), \(K_d=8\)):

Scenario: Heavy water usage (shower + dishwasher)

1. Tank drops: 75% → 70% → 65% in 2 minutes

2. Error grows: 10% below setpoint

3. P-term: 20 × 10 = 200 → pump at 100% (capped at max speed)

4. I-term accumulates: 0.8 × Σ(errors) = keeps pump running even as level recovers

5. D-term: Sees rapid level drop (de/dt large) → boosts pump early

6. Result: Tank refills to 75% in 8 minutes, stabilizes with ±1% fluctuationPerformance Metrics:

| Metric | Without PID (On/Off Control) | With PID Control |

|---|---|---|

| Level Stability | ±8% variation | ±1% variation |

| Pump Starts/Hour | 12 starts (wear and energy spikes) | 2-3 starts (soft start via PWM) |

| Water Shortage Events | 3 per month (tank empty) | 0 per year |

| Energy Consumption | 2.8 kWh/day (frequent on/off) | 2.1 kWh/day (smooth operation) |

| Pump Lifespan | ~3 years (mechanical stress) | ~7 years (gentle operation) |

215.6 When to Use PID vs Simpler Control

Not every IoT system needs PID control. Here’s a decision framework:

| Scenario | Control Strategy | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Simple on/off (LED, valve) | Bang-bang (on/off) control | No proportional control needed—device is either on or off |

| Slow process, low precision (room temp ±2°C OK) | Simple thermostat (on when cold, off when hot) | Thermal inertia provides natural smoothing |

| Fast process, high precision (drone, motor) | PID required | Must respond quickly and accurately to avoid instability |

| Multiple interacting variables (HVAC: temp + humidity) | Multi-loop PID or advanced control | Single-variable PID insufficient for coupled systems |

| Highly nonlinear (battery charging) | Look-up table + PID trim | PID struggles with extreme nonlinearity—hybrid approach better |

| Safety-critical (medical, automotive) | PID + redundancy + fault detection | Reliability and failsafes essential |

Rule of Thumb: - Bang-bang control: Simple, cheap, acceptable performance (±10% tolerance) - PID control: Moderate complexity, better performance (±1-2% tolerance) - Advanced control (MPC, adaptive): High complexity, optimal performance (<±0.5% tolerance)

IoT-Specific Considerations:

- Computational Resources: PID requires floating-point math—ensure MCU can handle it at required sample rate

- Sensor Quality: Noisy sensors → add filtering before PID or reduce derivative gain

- Communication Latency: If control loop spans cloud (sensor → cloud → actuator), latency may prevent effective PID → use edge computing

- Energy Constraints: Continuous PID sensing/actuation consumes power → consider duty-cycled control for battery devices

TipCross-Hub Connections

Interactive Learning Tools: - Simulations Hub - Try the PID Tuner Simulator to see how changing Kp, Ki, Kd affects system response - Videos Hub - Watch PID control demonstrations showing real controllers, tuning methods, and system stability - Quizzes Hub - Test your understanding of PID components, tuning, and control strategy selection

Knowledge Resources: - Knowledge Gaps Hub - Common misconceptions about PID tuning and stability explained - Knowledge Map - See how PID control connects to sensors, actuators, and system design

NoteRelated Chapters

This Series: - Processes & Systems: Core Definitions - What are processes and systems - Processes & Systems: Control Types - Open-loop vs closed-loop control

Deep Dives: - Process Control and PID - Advanced feedback control systems - Processes Labs and Review - Hands-on implementations - PID Feedback Fundamentals - Mathematical foundations

Foundation: - IoT Reference Models - System architecture layers - State Machines in IoT - Control state management

Sensing & Actuation: - Sensor Fundamentals - Input devices - Actuators - Output devices - Sensor Circuits - Interfacing

Design: - Energy Management - Power optimization - Hardware Prototyping - System building

215.7 Visual Reference Gallery

NoteVisual: Coffee Pot Control System Block Diagram

This visualization illustrates the fundamental closed-loop control concepts using a familiar household appliance, demonstrating how sensors, controllers, and actuators work together.

NoteVisual: Closed-Loop Feedback System

This diagram shows the general architecture of closed-loop feedback systems fundamental to understanding PID control and IoT process automation.

NoteVisual: Adding Integral Control Action

This figure demonstrates how integral control eliminates steady-state error by integrating accumulated error over time, a key concept in PID controller design.

215.8 Summary

This chapter covered PID control theory and applications for IoT:

- PID Control Theory: Learning the three control actions—Proportional (react to current error), Integral (eliminate accumulated error), and Derivative (predict and dampen oscillations)

- The PID Formula: Understanding the mathematical relationship \(u(t) = K_p \cdot e(t) + K_i \cdot \int e(\tau) d\tau + K_d \cdot \frac{de}{dt}\)

- PID Tuning: Finding optimal gain values (\(K_p\), \(K_i\), \(K_d\)) to balance response speed, stability, and precision

- Real-World PID Applications: Implementing feedback control in smart thermostats (temperature regulation), drones (orientation stability), and water tanks (level control)

- Cascaded Control: Using dual PID loops for improved performance in fast systems like drones

- Control Strategy Selection: Choosing appropriate control methods based on system dynamics, precision requirements, computational resources, and energy constraints

- IoT-Specific Considerations: Addressing computational resources, sensor noise, communication latency, and energy constraints in control design

215.9 What’s Next

The next chapter explores State Machines in IoT, introducing how to manage system modes and transitions. You’ll learn how state machines complement PID control by managing higher-level system behavior (startup, shutdown, fault handling) while PID handles continuous regulation within each state.