%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '14px'}}}%%

graph TB

Start[BLE Pairing Initiated]

Start --> TK[Temporary Key - TK<br/>Generated during pairing<br/>Based on pairing method]

TK --> STK[Short Term Key - STK<br/>AES-128 encrypted<br/>Valid for current session]

STK --> Decision{Bonding<br/>Enabled?}

Decision -->|Yes| LTK[Long Term Key - LTK<br/>128-bit permanent key<br/>Stored in flash memory]

Decision -->|No| Session[Session Only<br/>Keys discarded on disconnect]

LTK --> IRK[Identity Resolving Key - IRK<br/>For address resolution<br/>Privacy protection]

LTK --> CSRK[Connection Signature<br/>Resolving Key - CSRK<br/>For data signing]

LTK --> Reconnect[Future Reconnections<br/>Use stored LTK<br/>No re-pairing needed]

IRK --> RPA[Resolvable Private<br/>Address - RPA<br/>Changes every 15 min<br/>Prevents tracking]

CSRK --> Auth[Authenticated Data<br/>Integrity protection<br/>Replay attack prevention]

Session --> Disconnect[On Disconnect<br/>All keys erased<br/>Must re-pair next time]

style Start fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style TK fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style STK fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Decision fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style LTK fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style IRK fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style CSRK fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Session fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Reconnect fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style RPA fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Auth fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Disconnect fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

915 Bluetooth Security: Encryption and Key Management

915.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand BLE Encryption Architecture: Explain AES-CCM encryption and key generation methods

- Analyze Key Hierarchy: Describe the roles of LTK, IRK, and CSRK in BLE security

- Apply Security Decision Framework: Choose appropriate security levels for different applications

- Implement Best Practices: Configure secure pairing and key storage for IoT deployments

915.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- Bluetooth Security: Pairing Methods: Understanding BLE pairing process and method comparison

- Basic Cryptography Concepts: Familiarity with AES encryption and key exchange (ECDH)

915.3 BLE Encryption Architecture

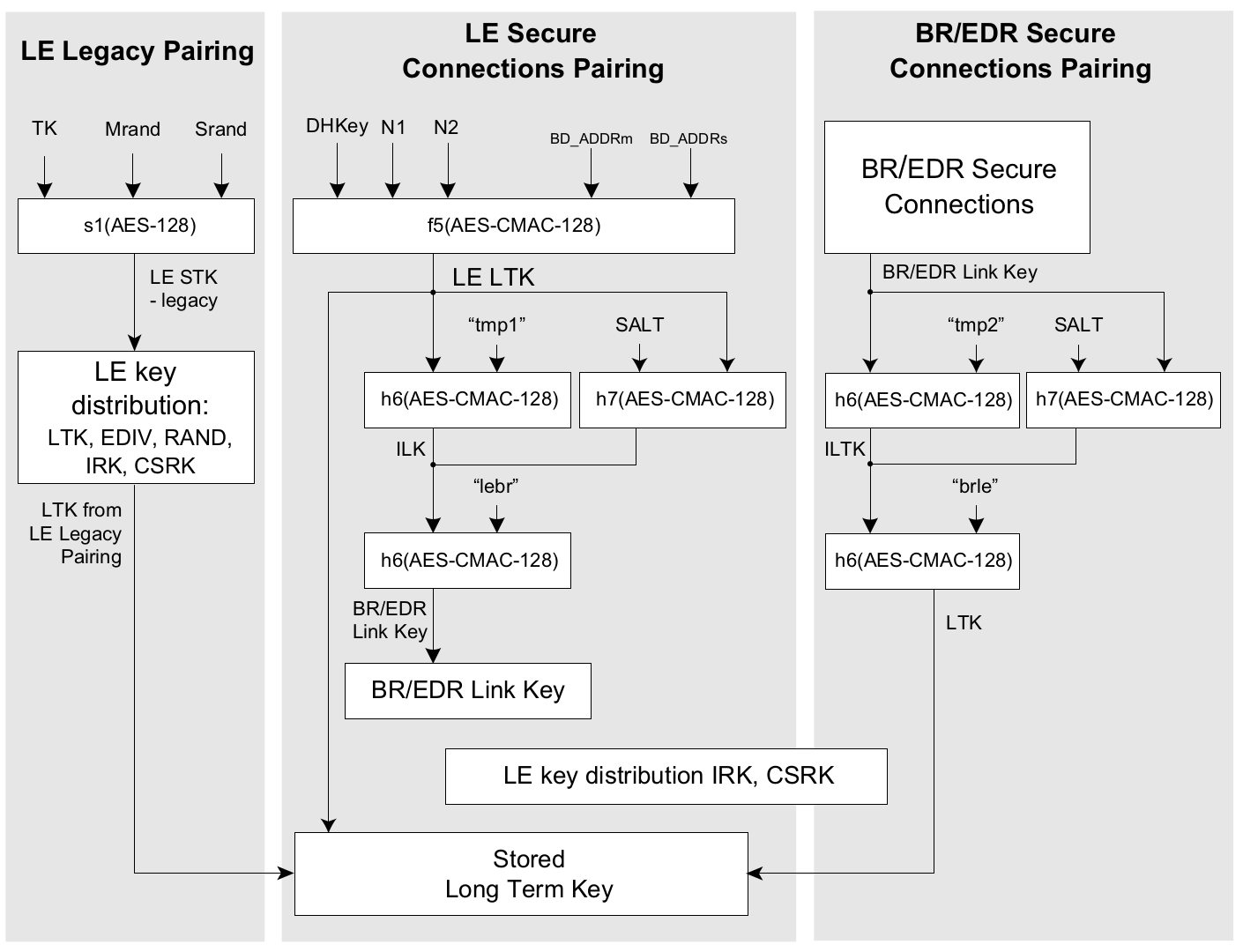

BLE supports multiple encryption architectures depending on the pairing method and Bluetooth version. The diagram below shows the key generation process for Legacy Pairing, LE Secure Connections, and BR/EDR Secure Connections.

Key Generation Methods:

| Method | Key Function | Input Parameters | Security Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| LE Legacy | s1(AES-128) | TK, Mrand, Srand | Basic (vulnerable to passive eavesdropping) |

| LE Secure Connections | f5(AES-CMAC-128) | DHKey, N1, N2, Addresses | Strong (ECDH protection) |

| BR/EDR Secure | h6/h7(AES-CMAC-128) | Link Key, SALT | Strong (cross-transport key derivation) |

915.4 BLE Key Hierarchy

Understanding the BLE key hierarchy is essential for implementing secure IoT applications:

Key Types Explained:

- TK (Temporary Key): Generated during pairing, depends on pairing method

- STK (Short Term Key): Session encryption key, derived from TK

- LTK (Long Term Key): Stored for bonding, enables reconnection without re-pairing

- IRK (Identity Resolving Key): Enables private address resolution for privacy

- CSRK (Connection Signature Resolving Key): For signing unencrypted data

915.5 Security Decision Framework

915.5.1 Choosing the Right BLE Security Level

Use “Just Works” ONLY when:

- Public beacon data (no sensitive information)

- Read-only sensor broadcasting (weather station)

- Device has no display, keyboard, or NFC

- Data is already encrypted at application layer

- Example: Public temperature beacon in park

- Risk acceptance: Anyone can read data (that’s the intent)

Use Passkey Entry when:

- Device has display OR keyboard (not both)

- Static PIN acceptable (e.g., printed on device)

- Moderate security sufficient

- Example: Wireless keyboard (displays 6-digit PIN)

- Security: 1 million possible PINs (secure if random)

- Weakness: Static PIN vulnerable if observed

Use Numeric Comparison when:

- Both devices have displays

- User can verify 6-digit code

- High security required

- Example: Smartphone pairing with tablet

- Security: 1 million codes + visual verification (prevents MITM)

- Best for: Consumer IoT (phones, smartwatches, tablets)

Use Out-of-Band (OOB) when:

- Maximum security required

- Device has NFC or can display QR code

- Medical, financial, or industrial applications

- Example: Payment terminal with NFC

- Security: Attacker must compromise both channels (Bluetooth + NFC/QR)

- Best for: Smart locks, medical devices, payment systems

915.5.2 Security Comparison Table

| Method | Auth Bits | MITM Protection | User Action | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Just Works | 0 | None | None | Public beacons only |

| Passkey Entry | ~20 (6-digit PIN) | If passkey is secret | Enter PIN | Keyboards, mice |

| Numeric Comparison | ~20 + visual | Strong (if user verifies) | Verify code | Smartphones, tablets |

| Out of Band (OOB) | Varies | Strong (if OOB channel is secure) | NFC tap / QR scan | Smart locks, commissioning |

Numbers explained:

- 0 bits (Just Works): No user-authenticated verification - vulnerable to active MITM during pairing

- ~20 bits (6-digit PIN): About 1,000,000 possibilities - treat as modest entropy

- OOB: Security depends on the out-of-band channel and the secret you exchange

915.5.3 Security Selection Decision Tree

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '13px'}}}%%

graph TD

Start{Is data<br/>sensitive?}

Start -->|No - Public data| Public[Public Beacon<br/>Just Works acceptable<br/>No pairing needed]

Start -->|Yes| Display{Do both devices<br/>have displays?}

Display -->|Yes| NumComp[Numeric Comparison<br/>6-digit code verification<br/>Strong MITM protection]

Display -->|No| OneDisplay{Does ONE device<br/>have display?}

OneDisplay -->|Yes| Passkey[Passkey Entry<br/>6+ digit random PIN<br/>Moderate security]

OneDisplay -->|No| Physical{Can user access<br/>device physically?}

Physical -->|Yes| OOB[Out-of-Band<br/>QR code or NFC tag<br/>Maximum security]

Physical -->|No| AppLayer[Just Works + App Layer<br/>Encrypt at application level<br/>Trade-off: Weaker BLE security]

NumComp --> Bonding1{Need<br/>auto-reconnect?}

Passkey --> Bonding2{Need<br/>auto-reconnect?}

OOB --> Bonding3{Need<br/>auto-reconnect?}

Bonding1 -->|Yes| Bond1[Enable Bonding<br/>Store LTK in secure storage<br/>Hardware keystore]

Bonding1 -->|No| NoBond1[Pairing Only<br/>Re-pair each session<br/>Higher security]

Bonding2 -->|Yes| Bond2[Enable Bonding<br/>Use secure key storage<br/>Consider audit logging]

Bonding2 -->|No| NoBond2[Pairing Only<br/>Limits long-term trust]

Bonding3 -->|Yes| Bond3[Enable Bonding<br/>Protect stored keys<br/>Support device revocation]

Bonding3 -->|No| NoBond3[Pairing Only<br/>Maximum paranoia mode]

Bond1 --> Final1[Consumer IoT<br/>Smartphones, wearables<br/>Good balance]

Bond2 --> Final2[Enterprise IoT<br/>Warehouse scanners<br/>Monitor closely]

Bond3 --> Final3[Critical Infrastructure<br/>Smart locks, medical<br/>Production ready]

NoBond1 --> Final4[High-security apps<br/>Banking, government<br/>Accept UX penalty]

style Start fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style Display fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style OneDisplay fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Physical fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Bonding1 fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Bonding2 fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Bonding3 fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Public fill:#E67E22,stroke:#c0392b,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style AppLayer fill:#f39c12,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Passkey fill:#f39c12,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style NumComp fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style OOB fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style Bond1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Bond2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Bond3 fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style NoBond1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style NoBond2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style NoBond3 fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Final1 fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Final2 fill:#f39c12,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Final3 fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style Final4 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

915.5.4 Security Decision Matrix

| Data Sensitivity | Minimum (Link-Layer) | Recommended Controls | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public | None (if acceptable) | Avoid pairing; sign data if integrity matters | Weather beacon |

| Personal | AES-CCM (encrypted link) | LE Secure Connections + bonding + privacy addresses | Fitness tracker |

| Medical / safety | AES-CCM (encrypted link) | Authenticated pairing (Numeric Comparison/OOB), secure firmware updates, strong device identity | Glucose monitor |

| Financial / high-value | AES-CCM (encrypted link) | OOB pairing where possible, hardened key storage, end-to-end authn/authz | Payment terminal |

| Industrial / control | AES-CCM (encrypted link) | Application-layer integrity/authentication, logging, and lifecycle key management | Factory sensor |

Note: Compliance requirements vary by jurisdiction and product. Link-layer encryption is important, but it is not sufficient on its own for most regulated systems.

915.6 Best Practices

Do:

- Pair in secure environment

- Use numeric comparison or OOB

- Update firmware regularly

- Disable when not needed

- Remove unused pairings

Don’t:

- Avoid “Just Works” mode for sensitive data

- Don’t pair unknown devices

- Never assume range limits provide security

915.7 Common Pitfalls

The Mistake: Implementing “Just Works” pairing for displayless IoT devices (sensors, beacons, smart plugs) because “there’s no way to show a PIN,” leaving devices permanently vulnerable to MITM attacks during every pairing attempt.

Why It Happens: Developers assume display-based verification (Numeric Comparison, Passkey) is the only option for secure pairing.

The Fix: Use Out-of-Band (OOB) pairing with a physical channel that attackers cannot intercept:

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '11px'}}}%%

flowchart TB

PROB["Displayless Device<br/>(No PIN/Display)"]

subgraph OOB["OUT-OF-BAND PAIRING OPTIONS"]

direction TB

subgraph QR["1. QR Code"]

QR1["Print unique pairing<br/>data at manufacturing"]

QR2["User scans QR<br/>with phone app"]

QR3["Physical access<br/>required"]

QR1 --> QR2 --> QR3

end

subgraph NFC["2. NFC Tap-to-Pair"]

NFC1["Embed NFC tag<br/>with credentials"]

NFC2["Phone taps device<br/>to exchange data"]

NFC3["4cm range limits<br/>remote attacks"]

NFC1 --> NFC2 --> NFC3

end

subgraph BTN["3. Button-Press Window"]

BTN1["Device accepts pairing<br/>30-60 sec after button"]

BTN2["User must be<br/>physically present"]

BTN3["Combine with per-device<br/>secret for auth"]

BTN1 --> BTN2 --> BTN3

end

end

PROB --> OOB

subgraph SEC["SECURITY COMPARISON"]

JW["Just Works:<br/>0 bits MITM protection"]

OOBSEC["OOB via QR/NFC:<br/>128 bits entropy"]

end

OOB --> SEC

style PROB fill:#E67E22,stroke:#c0392b,color:#fff

style OOB fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style QR fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style NFC fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style BTN fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style JW fill:#c0392b,stroke:#7F8C8D,color:#fff

style OOBSEC fill:#27ae60,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style SEC fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

The Mistake: Pairing a BLE device once with strong security (Numeric Comparison or OOB), then assuming the bonded connection is permanently secure - without protecting stored keys or implementing re-authentication for sensitive operations.

Why It Happens: Developers focus security effort on the initial pairing ceremony, but forget that Long Term Keys (LTK) stored in flash memory can be extracted, cloned, or used by anyone with physical access to either device.

The Fix: Implement defense-in-depth beyond pairing: protect key storage, add application-layer authorization, and consider periodic re-authentication:

// Defense layer 1: Secure key storage

// Use hardware-backed keystore when available (iOS Keychain, Android Keystore,

// secure elements on embedded devices)

// Defense layer 2: Application-layer authorization for sensitive commands

typedef enum {

CMD_READ_SENSOR, // Low risk: allow after BLE connection

CMD_UNLOCK_DOOR, // High risk: require app PIN + recent auth

CMD_FACTORY_RESET, // Critical: require physical button + app confirmation

CMD_FIRMWARE_UPDATE // Critical: require signed payload + user consent

} command_security_t;

bool authorize_command(command_t cmd, auth_context_t *ctx) {

switch (get_security_level(cmd)) {

case LOW:

return ctx->ble_authenticated; // BLE pairing sufficient

case HIGH:

return ctx->ble_authenticated &&

ctx->app_pin_verified &&

(time_now() - ctx->last_auth_time) < 300; // 5-min timeout

case CRITICAL:

return ctx->physical_button_pressed &&

ctx->app_confirmation_received;

}

}

// Defense layer 3: Key rotation and revocation

// - Implement "forget this device" that deletes LTK on both sides

// - Consider periodic re-pairing for high-security applications

// - Log pairing events for security auditing915.8 Understanding Checks

Scenario: A startup launches a Bluetooth smart lock for Airbnb hosts. During beta testing, security researchers demonstrate they can unlock any door during the initial pairing process by sitting in a car 20 meters away with a laptop. The lock uses “Just Works” pairing for “convenience” - no PIN entry required.

Think about:

- How can an attacker unlock the door without physical access?

- What specific vulnerability in “Just Works” pairing enables this attack?

- The lock has AES-128 encryption AFTER pairing - why doesn’t that prevent the attack?

- How would you redesign the lock’s security?

Key Insight: Authentication happens BEFORE encryption. “Just Works” provides:

- No user-authenticated verification step during pairing

- No protection against active MITM or pairing hijack during setup

- Link encryption does not help if the attacker becomes the paired/bonded device

Secure redesign options:

- Numeric Comparison: require the installer to confirm a code shown by the lock and the phone

- OOB commissioning: use an internal QR code / NFC tap so physical access is required to enroll

- Application-layer authorization: even after pairing, require explicit authorization for “unlock” commands

Scenario: You’re managing a fleet of 100 Bluetooth-connected medical devices (insulin pumps) in a hospital. Nurses complain that re-pairing tablets to pumps every shift change (3x/day) wastes 5 minutes per device. IT Security insists that bonding is disabled because “stored keys are a security risk if tablets are lost or stolen.”

Think about:

- What’s the actual security difference between pairing-only and bonding?

- How much time is wasted without bonding? (100 devices x 3 shifts x 5 min)

- Can you implement bonding securely with proper key management?

- What’s the risk if a bonded tablet is stolen?

Key Insight: Bonding = convenience vs. security trade-off, but can be mitigated:

With Bonding (SECURE implementation):

- Pair once, but store keys using a hardware/OS-backed keystore (when available)

- Require user authentication (PIN/biometric) before high-risk actions

- Support revocation (remove bonds when a tablet is lost) and remote wipe

- Consider a periodic re-authentication policy based on your risk model

- Log pairing/connection events for auditability

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '11px'}}}%%

flowchart LR

subgraph SECURE["BLE BONDING WITH SECURE KEY STORAGE"]

direction LR

S1["1. Initial Pairing<br/>Numeric Comparison<br/>(verify 6-digit code)"]

S2["2. Save LTK<br/>to OS Keystore<br/>(hardware-backed)"]

S3["3. Require<br/>User Auth<br/>before connect"]

S4["4. Admin Path<br/>to Revoke<br/>lost tablets"]

S5["5. Log Events<br/>for Audit"]

S1 --> S2 --> S3 --> S4 --> S5

end

style SECURE fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style S1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S3 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S4 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style S5 fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

Scenario: A device uses LE Legacy pairing and relies on a short, printed passkey/PIN (“unique per device”) for security. The team assumes “it’s encrypted, so it’s safe.”

Think about:

- Why does low-entropy user input (e.g., a 4-6 digit passkey) matter?

- Why can Legacy pairing be risky if an attacker records the pairing transcript?

- What changes when you use LE Secure Connections?

- Beyond pairing, what authorization checks should still exist for safety-critical commands?

Key Insight: Strong ciphers don’t help if key agreement/authentication is weak.

Risk framing (order-of-magnitude):

- 4-digit PIN: 10,000 guesses

- 6-digit passkey: 1,000,000 guesses (approximately 20 bits)

Safer alternatives:

- Prefer LE Secure Connections with Numeric Comparison or OOB when possible

- Avoid static/shared passkeys; treat printed codes as a usability step, not a long-term secret

- Add application-layer authorization (e.g., signed “unlock” commands, role checks) even after pairing

- Plan for revocation (remove bonds when devices are replaced/lost)

915.9 Summary

This chapter covered BLE encryption and key management:

- Encryption Architecture: AES-CCM with 128-bit keys, three key generation methods (Legacy, LE Secure Connections, BR/EDR)

- Key Hierarchy: TK -> STK -> LTK, plus IRK for privacy and CSRK for signatures

- Security Decision Framework: Match pairing method to data sensitivity and device capabilities

- Best Practices: Use secure key storage, implement authorization layers, plan for revocation

- Common Pitfalls: OOB alternatives for displayless devices, defense-in-depth beyond initial pairing

915.10 What’s Next

Continue to Bluetooth Security: Labs and Defense-in-Depth to learn about:

- Hands-on ESP32 BLE security lab demonstrations

- Defense-in-depth security layers for IoT deployments

- BLE attack timeline and vulnerability mitigation

- Interactive knowledge checks to test your understanding