%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D', 'noteTextColor': '#2C3E50', 'noteBkgColor': '#E8F6F3', 'noteBorderColor': '#16A085'}}}%%

graph LR

A["Microcontroller<br/>(ESP32)"]

B["Sensor 1<br/>(Temperature)"]

C["Display<br/>(OLED)"]

D["Storage<br/>(SD Card)"]

A -->|"UART<br/>(2 wires)"| B

A -->|"I2C<br/>(2 wires)"| C

A -->|"SPI<br/>(4+ wires)"| D

style A fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style B fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style C fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style D fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

792 Wired Communication Fundamentals

792.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the Binary Transmission Challenge: Explain how digital data is converted to electrical signals

- Compare Synchronous vs Asynchronous: Differentiate clock-shared and independent-clock communication

- Identify Network Topologies: Distinguish point-to-point, multi-drop, and multi-point configurations

- Explain Master-Slave Architecture: Describe how bus access is controlled to prevent collisions

- Choose Duplex Mode: Select full-duplex or half-duplex based on application requirements

792.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- Networking Basics: Understanding fundamental networking concepts including data transmission, protocols, and communication models

- Binary and Digital Logic: Understanding binary numbers, voltage levels (HIGH/LOW), and basic digital electronics

792.3 Getting Started (For Beginners)

Analogy: Wired protocols are like different languages for talking through wires.

Just like humans have different languages (English, Spanish, Mandarin), electronic devices have different “languages” for communicating through wires (I2C, SPI, UART).

Why Wired Protocols?: Microcontrollers and sensors need a shared “language” (protocol) to communicate through wires.

| Protocol | Wires Needed | Speed | Devices | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UART | 2 (TX, RX) | Slow-Medium | 2 only | GPS, Bluetooth modules |

| I2C | 2 (SDA, SCL) | Medium | Many (127) | Sensors, displays |

| SPI | 4+ (MOSI, MISO, SCK, CS) | Fast | Many | SD cards, fast sensors |

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TD

subgraph "UART: Point-to-Point"

U1["Device 1"]

U2["Device 2"]

U1 <-->|"TX/RX<br/>(2 wires)"| U2

end

subgraph "I2C: Multi-Drop Bus"

M["Master"]

S1["Slave 1"]

S2["Slave 2"]

S3["Slave 3"]

M ---|"SDA/SCL<br/>(2 wires)"| S1

M ---|"Shared Bus"| S2

M ---|"Shared Bus"| S3

end

subgraph "SPI: Multi-Point Star"

SP["Master"]

SL1["Slave 1"]

SL2["Slave 2"]

SP -->|"MOSI/MISO/SCK/CS1<br/>(4 wires)"| SL1

SP -->|"MOSI/MISO/SCK/CS2<br/>(5 wires)"| SL2

end

style U1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style U2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style M fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style SP fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style SL1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style SL2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

This variant visualizes the fundamental trade-off between protocol speed and implementation complexity - useful for choosing the right protocol for your project.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#E67E22', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085', 'tertiaryColor': '#E8F6F3', 'fontSize': '10px'}}}%%

flowchart LR

subgraph SIMPLE["Simple (Few Wires)"]

UART["UART<br/>2 wires<br/>115 kbps typ<br/>Point-to-point"]

I2C["I2C<br/>2 wires<br/>400 kbps typ<br/>Multi-device"]

end

subgraph COMPLEX["Complex (More Wires)"]

SPI["SPI<br/>4+ wires<br/>10+ Mbps<br/>High speed"]

QSPI["QSPI<br/>6 wires<br/>100+ Mbps<br/>Flash memory"]

end

UART -->|"Need more<br/>devices"| I2C

I2C -->|"Need more<br/>speed"| SPI

SPI -->|"Need max<br/>throughput"| QSPI

style UART fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I2C fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style SPI fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style QSPI fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

Key Insight: I2C is the “sweet spot” for most IoT sensor applications - minimal wires (2) with multi-device support. Only move to SPI when I2C’s ~400 kbps isn’t fast enough.

| Scenario | Best Choice | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Connect a GPS module | UART | GPS modules typically use serial |

| Connect 5 sensors | I2C | One bus for many devices |

| Read an SD card | SPI | Needs high speed |

| Connect a display | I2C or SPI | Depends on display type |

Rule of thumb:

- I2C = Default choice for most sensors (simple, few wires)

- SPI = When you need speed (SD cards, high-res displays)

- UART = Legacy devices, GPS, Bluetooth modules

At the local level, IoT devices communicate using wires. Sensors connect to microcontrollers via I2C, SPI, or UART. Industrial equipment uses RS-232. Understanding these protocols is essential for interfacing sensors, displays, and peripherals in IoT systems.

792.4 The Challenge: Transmitting Binary Data

792.4.1 Fundamental Problem

All IoT ecosystems communicate using binary protocols - endless trails of 0s and 1s.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22'}}}%%

graph LR

A["Data:<br/>Temperature = 25C"]

B["Binary:<br/>00011001"]

C["Signal:<br/>HIGH/LOW"]

D["Received:<br/>00011001"]

E["Data:<br/>25C"]

A --> B --> C --> D --> E

style A fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style B fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style C fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style D fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style E fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

The problem to solve:

How can we send 0s and 1s from one place to another?

Engineers have developed many solutions, each optimized for different scenarios.

792.4.2 Design Considerations

Choice of protocol depends on:

| Factor | Questions | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Distance | Same PCB? Same room? Same building? | Wire length limits speed |

| Speed | How fast must data move? | Faster = more complex circuitry |

| Safety | Security requirements? Interference? | Shielding, encryption costs |

| Cost | Budget constraints? | More wires = higher cost |

| Power | Battery or mains powered? | Low power = slower speeds |

792.5 Overview of Wired Communication Standards

792.5.1 Comparison Table

| Protocol | Wires | Sync/Async | Speed | Distance | Devices | Topology | IoT Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS-232 | 3-9 | Async | 115 kbps | 15m | 2 | Point-to-point | GPS modules, serial debugging |

| I2C | 2 | Sync | 400 kbps | <1m | 112 | Multi-drop | Sensors, displays, EEPROMs |

| SPI | 4+ | Sync | 10+ Mbps | <1m | Many | Multi-point | SD cards, displays, high-speed sensors |

At local level (same room/building), wired communication is most common for IoT device interconnections.

Table: Wired Communication Standards Comparison

| NAME | SYNC/ASYNC | TYPE | DUPLEX | MAX DEVICES | MAX SPEED (Kbps) | MAX DISTANCE (m) | PIN COUNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS-232 | async | point-to-point | full | 2 | 20 | 30 | 2 |

| RS-422 | async | multi-drop | half | 10 | 10,000 | 4,000 | 1 |

| RS-485 | async | multi-point | half | 32 | 10,000 | 4,000 | 2 |

| I2C | sync | multi-master | half | 112 | 3,400 | <1 | 2 |

| SPI | sync | multi-master | full | Many | >1,000 | <1 | 3+1 |

| 1-Wire | async | master/slave | half | Many | 16 | 1,000 | 1 |

| USB 2.0 | async | master/slave | half | 127 | 480,000 | 5 | 4 |

| USB 3.0 | async | master/slave | full | 255 | 5,000,000 | 5 | 8 |

792.6 Common Misconception

Misconception: “SPI is always faster than I2C because it uses more wires (4+ vs 2), so I should always choose SPI for better performance.”

Reality: While SPI can achieve higher speeds (10+ Mbps vs 400 kHz), the real-world performance difference is often negligible for most IoT applications:

Quantified Examples:

- BME280 Temperature Sensor:

- I2C @ 400 kHz: Reading temp/humidity/pressure takes ~8 ms

- SPI @ 10 MHz: Same reading takes ~5 ms

- Difference: 3 ms savings (37% faster)

- Reality: For a weather station reading every 10 seconds, this 3 ms difference is irrelevant (0.03% of cycle time)

- 0.96” OLED Display (128x64 px):

- I2C @ 400 kHz: Full screen refresh ~60 ms

- SPI @ 8 MHz: Full screen refresh ~30 ms

- Difference: 30 ms savings (50% faster)

- Reality: Both achieve 15+ fps, imperceptible to human eye

- SD Card Data Logging:

- I2C (not supported): N/A

- SPI @ 25 MHz: 512-byte sector write ~200 us

- Reality: Here SPI is essential not because of “more wires” but because SD cards don’t support I2C protocol

Why the misconception?

- Pin count does not equal performance: I2C’s 2-wire limitation isn’t the bottleneck; it’s the pull-up resistor RC time constant (rise time limits frequency)

- Protocol overhead: I2C has 7-bit addressing + ACK bits (9 bits per byte), while SPI has 8 bits per byte - but for multi-byte transfers, this overhead is ~10%

- Real bottleneck: Sensor conversion time (BME280 takes 8 ms to measure, regardless of interface speed)

When SPI truly matters:

- High-throughput: SD cards, high-resolution TFT displays (320x240+), camera modules

- Continuous streaming: Audio I2S (2.8 Mbps for 44.1 kHz stereo), DMA-driven data acquisition

- Low latency: Real-time motor control loops (<1 ms cycle time)

The trade-off: SPI saves 1-5 ms per transaction but costs 2-3 extra GPIO pins per device. For battery-powered IoT nodes with limited pins, I2C is often superior despite lower speed.

This variant presents wired communication selection through a decision-tree lens - useful for IoT designers choosing between UART, I2C, SPI, and RS-485 for specific hardware requirements.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': {'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#E67E22', 'secondaryColor': '#16A085', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D', 'fontSize': '11px'}}}%%

flowchart TD

START["Select Wired<br/>Interface"]

Q1{"Distance<br/>requirement?"}

Q2{"Multiple<br/>devices on<br/>same bus?"}

Q3{"Speed<br/>requirement?"}

Q4{"Pin count<br/>constraint?"}

UART["UART/RS-232<br/>2-3 wires, 115 kbps<br/>Point-to-point<br/>Best for: GPS,<br/>debug console"]

RS485["RS-485<br/>2 wires, 10 Mbps<br/>Multi-drop, 4000m<br/>Best for: Industrial,<br/>Modbus sensors"]

I2C["I2C<br/>2 wires, 400 kbps<br/>112 devices, <1m<br/>Best for: Sensors,<br/>EEPROMs, RTCs"]

SPI["SPI<br/>4+ wires, 10+ Mbps<br/>Fast transfers<br/>Best for: Displays,<br/>SD cards, ADCs"]

START --> Q1

Q1 -->|">10m"| RS485

Q1 -->|"<10m"| Q2

Q2 -->|"No<br/>(1 device)"| UART

Q2 -->|"Yes"| Q3

Q3 -->|">1 Mbps"| SPI

Q3 -->|"<1 Mbps"| Q4

Q4 -->|"Minimal<br/>(2 pins)"| I2C

Q4 -->|"Available<br/>(4+ pins)"| SPI

style START fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style Q1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Q2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Q3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Q4 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style UART fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style RS485 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I2C fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style SPI fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

792.7 Key Concepts

Before diving into specific protocols, understand these fundamental concepts:

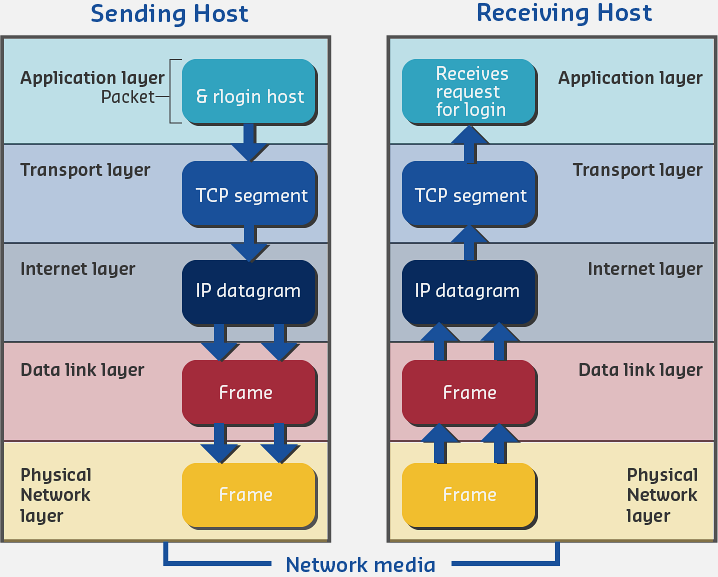

792.7.1 Protocol

Definition: A set of rules and conventions governing information exchange between devices.

Example: TCP/IP (seen in previous chapters) is a protocol suite for internet communication.

792.7.2 Synchronous vs Asynchronous Communication

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph "Synchronous (I2C, SPI)"

S1["Device A"]

S2["Device B"]

SC["Shared Clock"]

S1 -->|"Data"| S2

SC -.->|"Clock Signal"| S1

SC -.->|"Clock Signal"| S2

end

subgraph "Asynchronous (UART)"

A1["Device C<br/>Own Clock"]

A2["Device D<br/>Own Clock"]

A1 <-->|"Data + Start/Stop Bits"| A2

end

style S1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style SC fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style A1 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style A2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

Synchronous:

- Devices share a common clock transmitted on a dedicated wire

- Data synchronized to clock edges

- Simpler, more reliable

- Examples: I2C, SPI

Asynchronous:

- No clock wire transmitted

- Devices run independent clocks at same speed

- Data lines used for synchronization (start/stop bits)

- Example: RS-232, UART

792.7.3 Peer Communication

Definition: Entities at the same layer of a network that communicate with each other.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22'}}}%%

graph LR

M["Master<br/>(Layer 2)"]

S1["Slave 1<br/>(Layer 2)"]

S2["Slave 2<br/>(Layer 2)"]

M <-->|"Peer Communication"| S1

M <-->|"Peer Communication"| S2

style M fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

In wired protocols: Master and slave are peers at the same protocol layer.

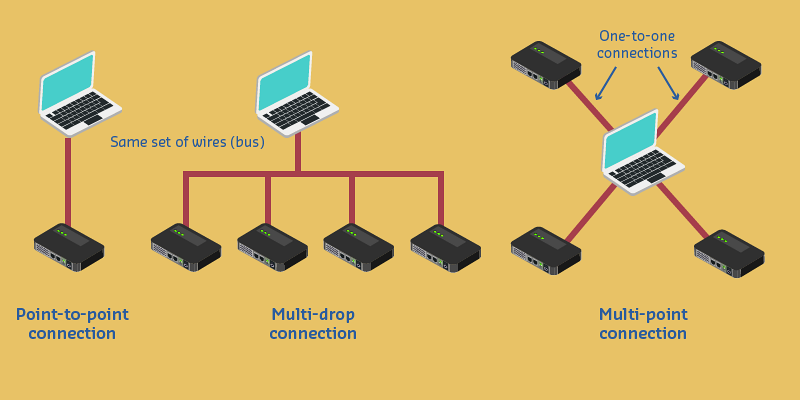

792.7.4 Point-to-Point, Multi-Drop, Multi-Point

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22'}}}%%

graph TD

subgraph "Point-to-Point (RS-232)"

PP1["Device A"]

PP2["Device B"]

PP1 <-->|"Dedicated Wires"| PP2

end

subgraph "Multi-Drop (I2C)"

MD["Master"]

MDS1["Slave 1"]

MDS2["Slave 2"]

MDS3["Slave 3"]

MD ---|"Shared Bus"| MDS1

MD ---|"Shared Bus"| MDS2

MD ---|"Shared Bus"| MDS3

end

subgraph "Multi-Point (SPI)"

MP["Master"]

MPS1["Slave 1"]

MPS2["Slave 2"]

MP -->|"CS1"| MPS1

MP -->|"CS2"| MPS2

end

style PP1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style PP2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style MD fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style MDS1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style MDS2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style MDS3 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style MP fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style MPS1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style MPS2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

Point-to-Point:

- Two devices using dedicated wires

- Example: RS-232

Multi-Drop:

- Many devices sharing same set of wires (bus)

- Example: I2C

Multi-Point:

- One master connecting to multiple slaves via dedicated wires

- Example: SPI with multiple chip select lines

792.7.5 Master/Slave Networks

Master device:

- Controls communication channel

- Initiates all transactions

- Determines when communication finishes

Slave devices:

- Respond to master requests

- Cannot talk directly to each other

- Must wait for master to grant access

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22'}}}%%

graph TB

M["Master<br/>(Controls Bus)"]

S1["Slave 1"]

S2["Slave 2"]

S3["Slave 3"]

M -->|"1. Request"| S1

S1 -->|"2. Response"| M

M -->|"3. Request"| S2

S2 -->|"4. Response"| M

S1 -.-x|"Cannot talk directly"| S2

S2 -.-x|"Cannot talk directly"| S3

style M fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style S3 fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

Prevents collisions: Only master controls when devices transmit.

792.7.6 Full-Duplex vs Half-Duplex

Full-Duplex:

- Both endpoints can transmit simultaneously

- Requires separate wires for each direction

- Example: SPI (MOSI and MISO wires)

Half-Duplex:

- Only one endpoint transmits at a time

- Can share single wire (bidirectional)

- Example: I2C (SDA line shared)

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22'}}}%%

graph LR

subgraph "Full-Duplex (SPI)"

FD1["Device A"]

FD2["Device B"]

FD1 -->|"MOSI"| FD2

FD2 -->|"MISO"| FD1

end

subgraph "Half-Duplex (I2C)"

HD1["Device C"]

HD2["Device D"]

HD1 <-->|"SDA (Shared)"| HD2

end

style FD1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style FD2 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style HD1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style HD2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

792.8 Summary

This chapter introduced the fundamental concepts of wired communication:

- Binary transmission challenge: Converting digital data to electrical signals requires standardized protocols

- Synchronous vs asynchronous: Clock-shared protocols (I2C, SPI) are simpler; independent-clock protocols (UART) need start/stop bits

- Network topologies: Point-to-point for dedicated links, multi-drop for shared buses, multi-point for star configurations

- Master-slave architecture: Prevents collisions by having one device control bus access

- Full vs half duplex: Trade-off between simultaneous bidirectional communication and wire count

792.9 What’s Next

Now that you understand wired communication fundamentals, explore the specific protocols:

- UART and RS-232: Serial point-to-point communication for GPS and debugging

- I2C Protocol: Two-wire bus for sensors, displays, and EEPROMs

- SPI Protocol: High-speed interface for SD cards and fast peripherals