%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph LLN["Low-Power and Lossy Network (LLN)"]

L1["10-40% Packet Loss"]

L2["Variable Link Quality"]

L3["Asymmetric Links"]

L4["Battery-Powered Devices"]

end

subgraph Constraints["IoT Device Constraints"]

C1["CPU: 8-32 MHz"]

C2["RAM: 10-128 KB"]

C3["Flash: 32-512 KB"]

C4["Power: Milliwatts"]

end

RPL["RPL Protocol<br/>Designed for LLNs"]

LLN --> RPL

Constraints --> RPL

style LLN fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Constraints fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style RPL fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff,stroke-width:3px

style L1 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style L2 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style L3 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style L4 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style C1 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style C2 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style C3 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style C4 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

708 RPL Introduction and Core Concepts

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand why traditional routing protocols don’t work for Low-Power and Lossy Networks (LLNs)

- Explain RPL as a distance-vector routing protocol for IoT

- Understand DODAG (Destination Oriented Directed Acyclic Graph) topology

- Explain the RANK concept and loop prevention mechanisms

708.1 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- Routing Fundamentals: Knowledge of basic routing concepts, routing tables, and distance-vector protocols helps you understand RPL’s routing decisions

- 6LoWPAN Fundamentals: RPL typically operates with 6LoWPAN, so familiarity with IPv6 header compression and adaptation layer mechanisms is important

- Wireless Sensor Networks: Understanding WSN energy constraints and multi-hop communication patterns explains RPL’s design choices and optimization strategies

This Series: - RPL Introduction - This chapter - RPL DODAG Construction and Modes - Building DODAGs and routing modes - RPL Traffic Patterns and Design - Traffic patterns and network design lab - RPL Production and Summary - Production framework and key takeaways

Comparisons: - Routing Fundamentals - Distance-vector vs link-state routing - 6LoWPAN Fundamentals - RPL integration with IPv6 compression - Thread Comprehensive Review - Alternative routing in Thread/Matter networks

Hands-On: - RPL Production and Review - Storing vs Non-Storing mode deployment - Simulations Hub - Test RPL DODAG formation in simulators

Imagine a smart building with 500 sensors spread across 20 floors. Sensor data needs to reach a central controller on the ground floor, but not every sensor can communicate directly—wireless signals don’t penetrate all walls and floors. Sensors need to relay messages through other sensors to reach the destination. This is called multi-hop routing.

But here’s the problem: traditional Internet routing protocols (like those used in Wi-Fi routers) assume devices have plenty of battery power, memory, and processing capability. IoT sensors have tiny batteries, minimal memory, and weak processors. Running traditional routing protocols would drain batteries in days.

RPL (Routing Protocol for Low-power and Lossy networks) is designed specifically for this challenge. It creates a tree-like structure where all data flows “upward” toward a central point (called the “root”), like water flowing downhill to a river. This structure is called a DODAG (Destination-Oriented Directed Acyclic Graph)—a fancy way of saying “tree where all paths lead to the root without loops.”

Think of it like an organization chart: employees report to managers, managers report to directors, directors report to the CEO. Messages flow up the hierarchy efficiently without getting stuck in circles. RPL does this for sensors, ensuring data reaches the gateway while conserving precious battery power.

| Term | Simple Explanation |

|---|---|

| RPL | Routing Protocol for Low-power and Lossy networks—designed for IoT |

| Multi-hop | Messages relay through multiple devices to reach destination |

| DODAG | Tree structure where all paths lead to root (like org chart) |

| Root | Central node where all data ultimately flows (gateway/coordinator) |

| RANK | Device’s distance from root—like floors in a building |

| Upward Route | Data flowing from sensors toward root |

| Downward Route | Commands flowing from root toward specific sensors |

| LLN | Low-power and Lossy Network—constrained IoT environment |

708.2 Introduction to RPL

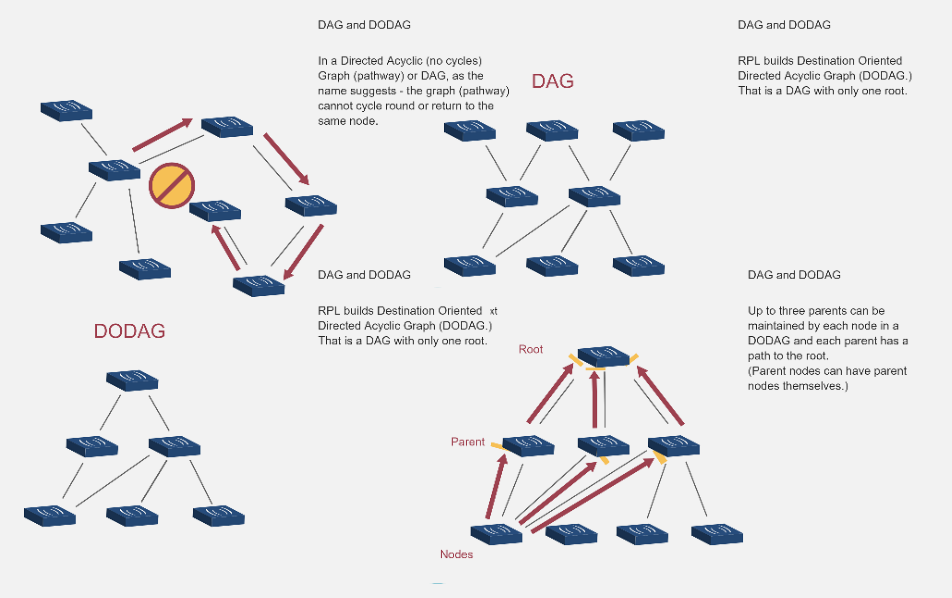

RPL (IPv6 Routing Protocol for Low-Power and Lossy Networks) is a distance-vector routing protocol specifically designed for resource-constrained IoT devices operating in challenging network conditions.

IoT routers, like other devices in an IoT environment, are resource constrained. As they operate in Low Power and Lossy Networks (LLN), there are limitations that make it almost impossible to use traditional routing protocols.

{fig-alt=“Diagram showing Low-Power and Lossy Network characteristics (packet loss, variable links, asymmetric links, battery power) and IoT device constraints (limited CPU, RAM, flash, power) both pointing to RPL protocol as the designed solution”}

Test your understanding of these networking concepts.

708.3 RPL Specification

- Standard: RFC 6550 (IETF, March 2012)

- Type: Distance-vector routing protocol

- Network Layer: IPv6 (works with 6LoWPAN)

- Topology: DODAG (Destination Oriented Directed Acyclic Graph)

- Metrics: Flexible (hops, ETX, latency, energy, etc.)

- Use Case: Low-power, lossy networks with many-to-one traffic patterns

708.4 Why Not Use Existing Routing Protocols?

Traditional routing protocols like OSPF, RIP, and AODV were designed for different network characteristics. They don’t work well for IoT because:

708.4.1 Processing, Memory, and Power Constraints

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph LR

subgraph Traditional["Traditional Router<br/>(OSPF/RIP)"]

T1["CPU: GHz multi-core"]

T2["RAM: GB"]

T3["Power: Watts"]

T4["Complex routing tables"]

end

subgraph IoT["IoT Sensor"]

I1["CPU: 32 MHz single"]

I2["RAM: 32 KB"]

I3["Power: mW battery"]

I4["Parent pointer only"]

end

VS["Incompatible"]

Traditional -.-> VS

IoT -.-> VS

style Traditional fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style IoT fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style VS fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff,stroke-width:3px

style T1 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#7F8C8D,color:#2C3E50

style T2 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#7F8C8D,color:#2C3E50

style T3 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#7F8C8D,color:#2C3E50

style T4 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#7F8C8D,color:#2C3E50

style I1 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style I2 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style I3 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style I4 fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

{fig-alt=“Comparison showing traditional router requirements (GHz CPU, GB RAM, watts power, complex tables) versus IoT sensor constraints (32 MHz CPU, 32 KB RAM, milliwatts battery, parent pointer only) highlighting incompatibility”}

Traditional Protocols Require: - Complex routing tables: OSPF maintains link-state database of entire network - Frequent updates: RIP sends entire routing table every 30 seconds - Heavy processing: Link-state algorithms (Dijkstra’s shortest path) - Power-hungry: Constant listening and periodic broadcasts

IoT Constraints: - Microcontroller: 8-32 MHz, single core - RAM: 10-128 KB (vs GB in traditional routers) - Flash: 32-512 KB (limited code and data storage) - Power: Milliwatts (battery-powered, years of operation)

708.4.2 Single Metric Not Always Appropriate

Traditional protocols use single metric: - RIP: Hop count only - OSPF: Cost (usually based on bandwidth)

IoT requires multiple, context-dependent metrics: - Latency: Real-time monitoring (industrial sensors) - Reliability: Critical data (medical devices) - Energy: Battery-powered devices (maximize lifetime) - Bandwidth: Mixed traffic (sensors + actuators)

RPL Solution: Supports objective functions with multiple metrics

708.4.3 Multiple Routing Instances

IoT Scenario: Single physical network, multiple applications

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

Physical["Same Physical Network<br/>100 IoT Devices"]

subgraph Instance1["RPL Instance 1<br/>Latency Optimized"]

I1_App["Temperature Monitoring"]

I1_Metric["Metric: Minimize Latency"]

I1_Parent["Fast parent selection"]

end

subgraph Instance2["RPL Instance 2<br/>Energy Optimized"]

I2_App["Firmware Updates"]

I2_Metric["Metric: Minimize Energy"]

I2_Parent["Low-power parent selection"]

end

Physical --> Instance1

Physical --> Instance2

style Physical fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff,stroke-width:3px

style Instance1 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Instance2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style I1_App fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style I1_Metric fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style I1_Parent fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#16A085,color:#2C3E50

style I2_App fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style I2_Metric fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

style I2_Parent fill:#F8F9FA,stroke:#E67E22,color:#2C3E50

{fig-alt=“Multiple RPL instances on same physical network: Instance 1 optimizes for latency (temperature monitoring) with fast parent selection, Instance 2 optimizes for energy (firmware updates) with low-power parent selection”}

Example: - Instance 1: Temperature monitoring (minimize latency) - Instance 2: Firmware updates (minimize energy, can be slower) - Same devices, different routing decisions based on application

708.4.4 Point-to-Multipoint Traffic Patterns

Traditional networks: Assume peer-to-peer traffic

IoT networks: Predominantly many-to-one traffic - Many sensors -> One gateway (cloud) - Data aggregation at root

RPL Optimization: Optimized for convergent traffic towards root

708.4.5 Lossy Links

Traditional networks: Assume reliable links (wired, enterprise Wi-Fi)

Low-Power and Lossy Networks (LLN): - High packet loss: 10-40% (vs < 1% wired) - Variable link quality: Interference, fading, obstacles - Asymmetric links: A can hear B, but B can’t hear A - Time-varying: Link quality changes over time

RPL Features for Lossy Networks: - Trickle timer: Adaptive control message frequency - ETX metric: Expected Transmission Count (accounts for retransmissions) - Loop avoidance: RANK prevents routing loops

708.5 RPL Core Concepts

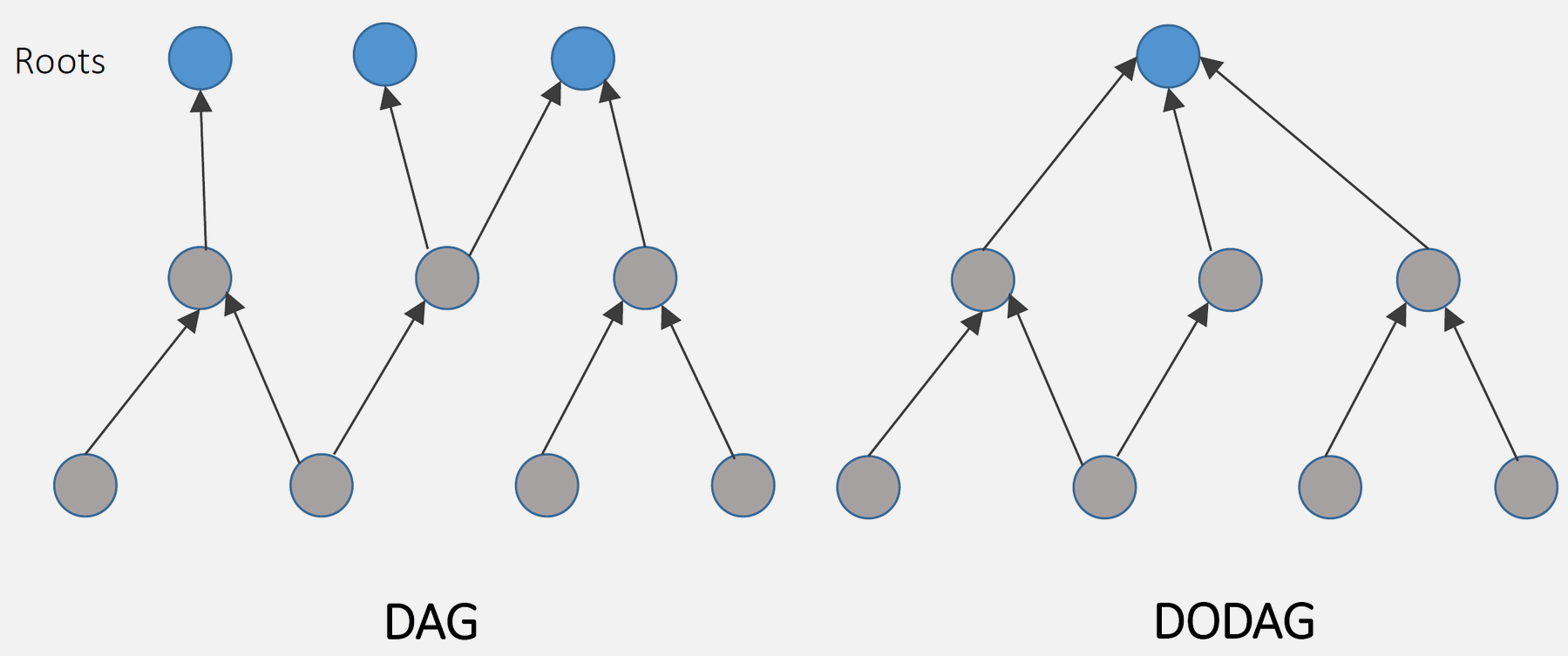

708.5.1 Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)

DAG = Directed Acyclic Graph

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

A["Node A"]

B["Node B"]

C["Node C"]

D["Node D"]

E["Node E"]

A --> B

A --> C

B --> D

C --> D

D --> E

style A fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style B fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style C fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style D fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style E fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

{fig-alt=“Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) example showing nodes A through E connected with directed arrows flowing downward, demonstrating no cycles - cannot return to same node following edges”}

Key Properties: - Directed: Edges have direction (arrows) - Acyclic: No cycles (cannot return to same node following edges) - Graph: Nodes connected by edges

Why DAG? - Loop-free routing: By definition, no cycles = no routing loops - Hierarchical structure: Natural parent-child relationships - Efficient aggregation: Data flows towards root(s)

708.5.2 DODAG (Destination Oriented DAG)

RPL uses DODAG: DAG with single root (destination)

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

ROOT["ROOT<br/>(Single Destination)<br/>Rank: 0"]

A["Node A<br/>Rank: 256"]

B["Node B<br/>Rank: 256"]

C["Node C<br/>Rank: 512"]

D["Node D<br/>Rank: 512"]

E["Node E<br/>Rank: 768"]

F["Node F<br/>Rank: 768"]

ROOT --> A

ROOT --> B

A --> C

A --> D

B --> D

C --> E

D --> F

style ROOT fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff,stroke-width:4px

style A fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style B fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style C fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style D fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style E fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style F fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

{fig-alt=“Destination Oriented Directed Acyclic Graph (DODAG) with single ROOT node at top (Rank 0), intermediate nodes at Rank 256 and 512, leaf nodes at Rank 768, all paths flowing toward root”}

DODAG Properties: - Single root: One destination (typically border router/gateway) - Upward routes: All paths lead to root - RANK: Position in DODAG hierarchy (root = 0, increases going down)

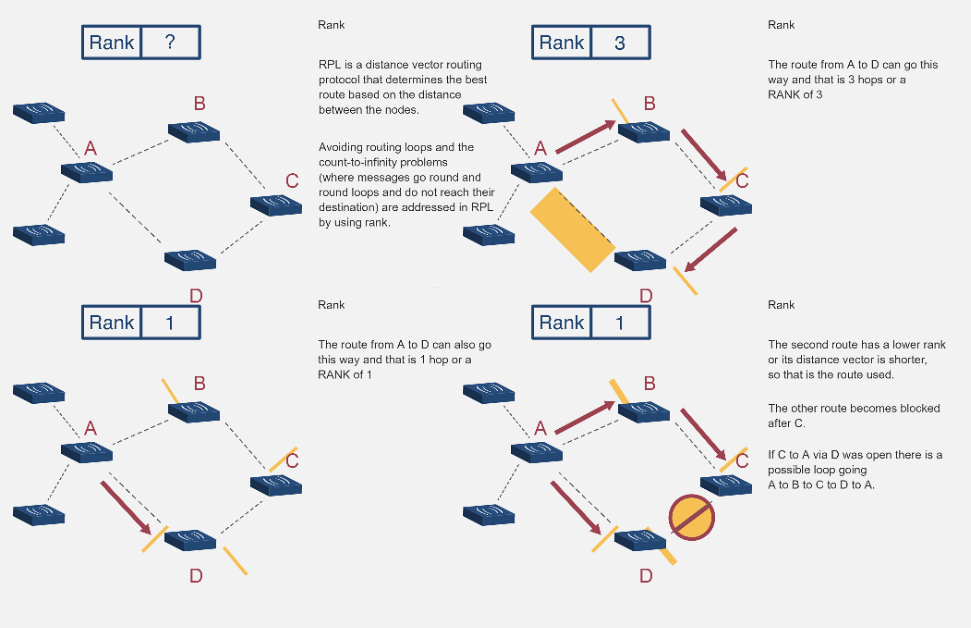

708.5.3 RANK: Loop Prevention Mechanism

RANK is a scalar representing a node’s position relative to the root.

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

ROOT["ROOT<br/>RANK = 0"]

A["Node A<br/>RANK = 100"]

B["Node B<br/>RANK = 250"]

C["Node C<br/>RANK = 370"]

ROOT -->|"Good link<br/>+100"| A

A -->|"Poor link<br/>+150"| B

B -->|"Good link<br/>+120"| C

C -.->|"Cannot choose<br/>(370 > 100 = loop!)"| A

style ROOT fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff,stroke-width:4px

style A fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style B fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style C fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

{fig-alt=“RANK loop prevention mechanism showing ROOT at Rank 0, Node A at 100, B at 250, C at 370, with valid forward links and forbidden backward link from C to A that would create a loop”}

RANK Rules: 1. Root has RANK 0 (or minimum RANK) 2. RANK increases as you move away from root 3. Upward routing: Packets forwarded to nodes with lower RANK 4. Loop prevention: Node cannot choose parent with higher RANK

RANK Calculation:

RANK(node) = RANK(parent) + RankIncrease

RankIncrease calculated based on:

- Link cost (ETX, RSSI, etc.)

- Number of hops

- Energy consumed

- Objective functionExample:

ROOT: RANK = 0

Node A (parent: ROOT): RANK = 0 + 100 = 100

Node B (parent: Node A): RANK = 100 + 150 = 250

Node C (parent: Node B): RANK = 250 + 120 = 370Loop Prevention: - Node C cannot choose Node A as parent (RANK 100 < 370 is OK) - Node A cannot choose Node C as parent (RANK 370 > 100 - would create loop)

RANK is not the same as Hop Count (although hop count can be a factor)

RANK is calculated using objective function which may consider: - Hop count - Expected Transmission Count (ETX) - Latency - Energy consumption - Link quality (RSSI, LQI)

Example: - Good link, 1 hop: RANK increase = 100 - Poor link, 1 hop: RANK increase = 300 - Good link, 2 hops: RANK increase = 200

Node may prefer 2 hops via good links (total RANK increase: 200) over 1 hop via poor link (RANK increase: 300).

708.6 What’s Next

Now that you understand RPL’s core concepts—DODAG topology, RANK mechanism, and why traditional protocols don’t work for IoT—the next chapter covers how RPL actually builds the DODAG and the two operational modes.

Continue to: RPL DODAG Construction and Modes

- DODAG construction process step-by-step

- DIO, DIS, DAO control messages

- Storing mode vs Non-Storing mode comparison

- Memory and performance trade-offs