701 RPL Trickle Algorithm and Routing Modes

701.1 Trickle Algorithm and Routing Modes

NoteLearning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the Trickle algorithm for adaptive control message timing

- Compare Storing mode vs Non-Storing mode trade-offs

- Design RPL networks for different IoT applications

- Analyze RPL performance trade-offs for traffic patterns

701.2 Understanding Trickle: The “Polite Gossip” Protocol

The Trickle algorithm is RPL’s secret weapon for efficient network-wide consistency. Think of it as a polite conversation at a party:

TipThe Party Metaphor: How Trickle Works

Imagine you’re at a party where everyone should know the same information (like when dinner is served):

The Social Dynamics:

At a party, if everyone says the same thing (consistent state), you stay quiet. But if you hear something different (inconsistency), you speak up. Over time, conversation naturally decreases as consensus forms.

The Five Rules of Polite Gossip:

- Listen first: When you arrive, listen to what others are saying (gather neighbor DIOs)

- Stay quiet if consistent: If everyone’s saying the same thing, no need to repeat (suppress transmission)

- Speak up if different: If you hear something wrong, correct it immediately (reset interval on inconsistency)

- Gradually relax: As consensus forms, conversations naturally decrease (double interval on stability)

- Reset on news: When new information arrives, the buzz picks up again (interval reset)

This is exactly how RPL nodes behave when spreading DODAG information!

Technical Mapping: Party to Network:

| Party Element | Trickle Mechanism | Technical Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Party | RPL Network | DODAG topology |

| Gossip | DIO messages | DODAG Information Objects |

| Same story | Consistent state | Same DODAG Version, RANK, parent |

| Different story | Inconsistency | New Version, RANK change, topology change |

| Listen period | Interval timer I |

Current interval: Imin <= I <= Imax |

| Counter | Consistency counter c |

How many consistent DIOs heard |

| Threshold | Redundancy constant k |

Suppress if c >= k |

| Speak up | Broadcast DIO | Share DODAG information |

| Stay quiet | Suppress transmission | Save energy when c >= k |

| Conversation dying down | Double interval | I = min(2xI, Imax) |

| New gossip | Reset interval | I = Imin on inconsistency |

How Trickle Achieves Efficiency:

{fig-alt=“Trickle algorithm state machine showing Listen phase collecting neighbor DIOs, CheckConsistency evaluating if counter threshold k is met, branching to Suppress (save energy), Broadcast (maintain awareness), or Inconsistent (urgent update), followed by DoubleInterval for stable networks or ResetInterval for network changes, creating adaptive control message frequency”}

NoteAcademic Resource: Trickle Execution Example

The Cambridge Mobile and Sensor Systems course demonstrates Trickle timing with a 3-node example using redundancy threshold k=1:

Timeline Analysis:

| Time | Node 1 | Node 2 | Node 3 | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t=0 | c=0 | c=0 | c=0 | All start listening |

| t1a | TX | - | - | Node 1 transmits (c=0 < k=1) |

| t1a-all | - | c=1 | c=1 | Nodes 2,3 increment c on reception |

| t2a | - | SUPPRESS | - | Node 2 suppresses (c=1 >= k=1) |

| t2b | - | - | SUPPRESS | Node 3 suppresses (c=1 >= k=1) |

| interval x 2 | - | - | - | All nodes double interval (stable) |

Key Insight: When k=1, nodes suppress transmission after hearing just one consistent message from a neighbor. This exponentially reduces overhead while maintaining network awareness.

Source: University of Cambridge - Mobile and Sensor Systems (Prof. Cecilia Mascolo)

701.3 Trickle Timer Behavior: The Three Scenarios

NoteScenario 1: Stable Network (Doubling Interval)

What happens: Everyone at the party is saying the same thing, so conversation naturally dies down.

Technical behavior: - Node starts interval I = Imin (e.g., 10s) - During listening period, hears k or more consistent DIOs from neighbors - Suppresses transmission (stays quiet) - Doubles interval: I = min(2xI, Imax) - Next interval: 10s to 20s to 40s to 80s to … to 1 hour

Example timeline:

t=0s: I=10s, Heard 5 DIOs (all RANK=100), Suppress, Next I=20s

t=20s: I=20s, Heard 4 DIOs (all RANK=100), Suppress, Next I=40s

t=60s: I=40s, Heard 3 DIOs (all RANK=100), Suppress, Next I=80s

t=140s: I=80s, Heard 2 DIOs (all RANK=100), Suppress, Next I=160s

...

t=3600s: I=3600s (1 hour), Heard 1 DIO, Suppress, Stay at I=3600s (Imax)Energy savings: After 10 doublings, a node that would have sent 360 DIOs/hour now sends just 1 DIO/hour = 360x reduction!

WarningScenario 2: Network Inconsistency (Reset Interval)

What happens: Someone says something different at the party—everyone starts talking to correct it!

Technical behavior: - Node hears DIO with different DODAG information: - Different DODAG Version Number - Parent changed RANK - New Objective Function - Immediately broadcasts DIO to share correct information - Resets interval: I = Imin (back to minimum) - Counter resets: c = 0 - Network rapidly converges to new consistent state

Example timeline:

t=0s: I=3600s (stable at 1 hour interval)

t=100s: INCONSISTENCY DETECTED! Parent RANK changed 100->150

-> Broadcast DIO immediately

-> Reset I=10s (Imin)

-> Reset counter c=0

t=110s: I=10s, Heard 6 DIOs (all consistent with new RANK), Suppress, I=20s

t=130s: I=20s, Heard 5 DIOs (consistent), Suppress, I=40s

t=170s: I=40s, Heard 4 DIOs (consistent), Suppress, I=80s

...

(Network re-stabilizes and returns to hourly DIOs)Why this matters: Topology changes propagate in seconds (multiple nodes reset timers), but stable network returns to hourly updates = responsive yet efficient!

TipScenario 3: Insufficient Redundancy (Broadcast)

What happens: Not enough people are talking at the party—you chime in to maintain awareness.

Technical behavior: - Node hears fewer than k consistent DIOs during interval - Counter c < k (e.g., c=1, k=3) - Broadcasts DIO to ensure information dissemination - Doubles interval normally: I = min(2xI, Imax) - Ensures at least k nodes transmit per interval (redundancy)

Example scenario:

Sparse network area (only 2 neighbors):

t=0s: I=10s, Heard 1 DIO (c=1 < k=3), BROADCAST DIO, Next I=20s

t=20s: I=20s, Heard 2 DIOs (c=2 < k=3), BROADCAST DIO, Next I=40s

t=60s: I=40s, Heard 2 DIOs (c=2 < k=3), BROADCAST DIO, Next I=80sNetwork edge behavior: Nodes at DODAG edges (fewer neighbors) broadcast more frequently to maintain connectivity, while dense core suppresses aggressively.

701.4 Why Trickle Saves Energy in Stable Networks

The genius of Trickle is exponential backoff combined with instant reset:

Energy math: - Periodic DIO (no Trickle): Send every 10s = 360 DIOs/hour = 360 transmissions - Trickle (stable network): Send every 1 hour = 1 DIO/hour = 1 transmission - Savings: 99.7% reduction in control overhead!

Real-world battery impact:

{fig-alt=“Trickle energy savings diagram comparing 360 DIOs/hour without Trickle (16.2 mAh/hour) vs 1 DIO/hour with Trickle (0.045 mAh/hour), showing 99.7% reduction and 141.6 Ah/year saved, extending battery life by 5-10 months”}

Assumptions: 5mA transmit current, 3ms transmission time, 2000mAh battery

Why This Matters for IoT:

The Trickle algorithm enables RPL to achieve network-wide consistency with minimal energy expenditure:

- Stable network (99% of the time): Nodes send DIOs every 10-60 minutes, conserving battery

- Network change (1% of the time): Nodes send DIOs every 10-500ms for rapid convergence

- Polite suppression: If 5 neighbors already broadcasted the same DIO, no need to add redundancy

- Instant reaction: Inconsistency (e.g., RANK change, parent failure) triggers immediate reset to fast interval

Real-world impact: In a 100-node smart building, Trickle reduces DIO overhead from ~600,000 messages/day (periodic every 10s) to ~14,400 messages/day (adaptive, mostly hourly), extending battery life by 41x while maintaining sub-minute response to topology changes.

RFC 6206 Parameters: - Imin: Minimum interval (10ms-1s) - fast response to changes - Imax: Maximum interval (1min-1hr) - low overhead when stable - k: Redundancy constant (2-8) - consistency threshold before suppression - c: Listen-only period (0-50% of interval) - gather info before deciding

701.5 Trickle Algorithm: Visual Explanation

Trickle is “polite gossip” - nodes share information only when needed.

701.5.1 The Algorithm in 4 Steps

{fig-alt=“Trickle algorithm 4-step visual flowchart showing Step 1 (navy) initializing interval I to Imin, resetting counter c to 0, and picking random transmission time t; Step 2 (teal) listening for consistent information and incrementing counter; Step 3 (orange) decision point checking if counter c is less than redundancy constant k, branching to Transmit if yes or Stay Silent if no; Step 4 (navy) doubling the interval up to Imax and restarting the cycle, demonstrating adaptive control message frequency for RPL networks”}

701.5.2 Key Parameters

| Parameter | Meaning | Typical Value |

|---|---|---|

| Imin | Minimum interval (fast response) | 100ms |

| Imax | Maximum interval (energy saving) | 16 minutes |

| k | Redundancy constant (suppression threshold) | 1-5 |

| c | Consistency counter (heard transmissions) | Incremented per consistent message |

| t | Random transmission time in [I/2, I] | Prevents collisions |

701.5.3 Why Trickle Works

- Consistent network: Everyone agrees, intervals grow exponentially, minimal traffic

- Inconsistency detected: Reset interval to Imin, quick resync across network

- New node joins: Hears inconsistent info, triggers rapid updates from neighbors

- Suppression: If enough neighbors already transmitted (c >= k), stay silent to save energy

701.6 RPL Routing Modes

RPL supports two modes with different memory/performance trade-offs:

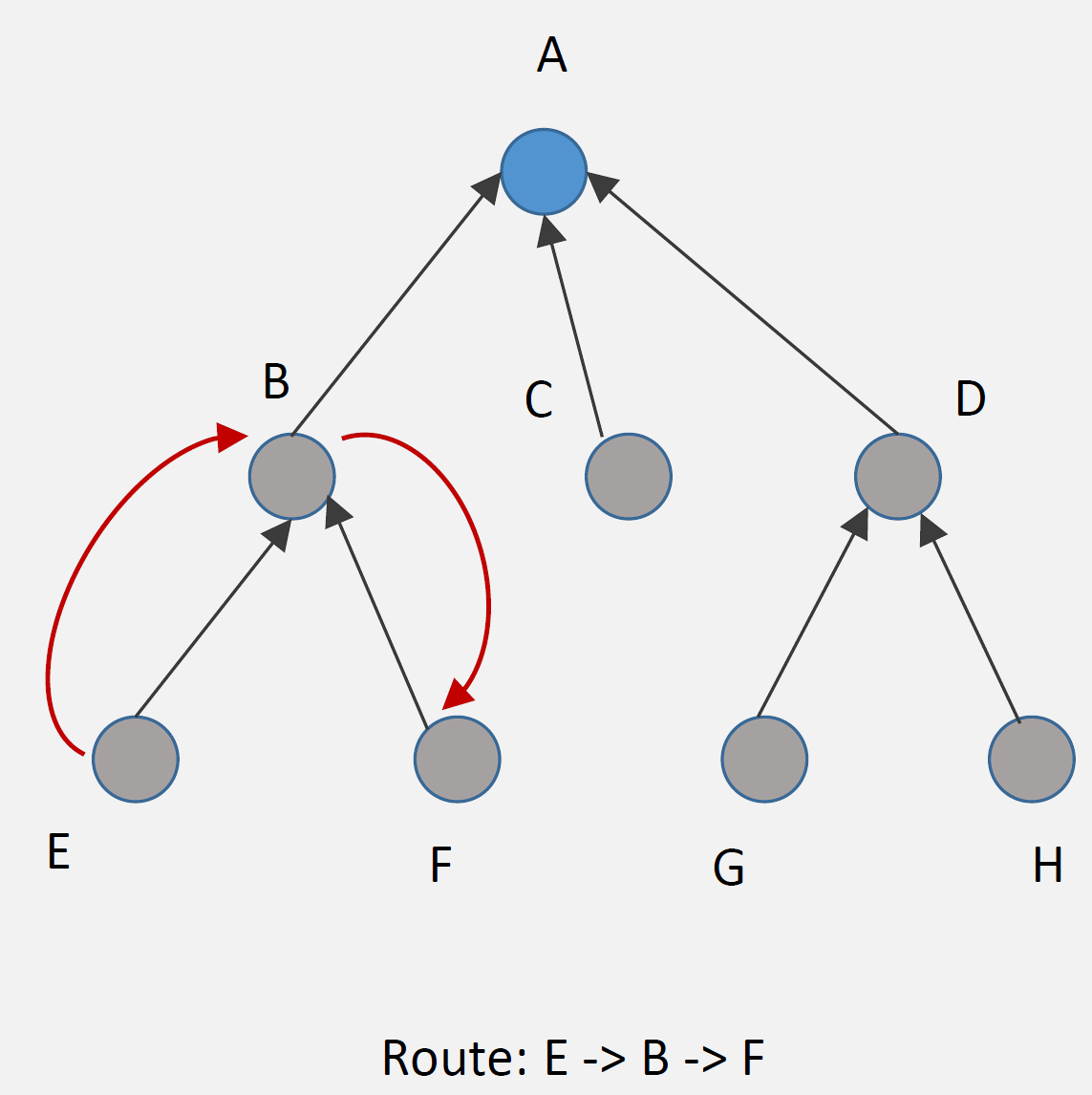

701.6.1 Storing Mode

Each node maintains routing table for its sub-DODAG.

{fig-alt=“RPL Storing mode showing distributed routing tables: ROOT maintains routes to all nodes, intermediate nodes B and C maintain routes to their descendants, enabling distributed forwarding decisions”}

How It Works: 1. DAO messages: Nodes advertise reachability to parents 2. Routing tables: Each node stores routes to descendants 3. Packet forwarding: Node looks up destination in table, forwards to appropriate child

Example Route (E to F):

Step 1: E sends packet to parent B (upward)

Step 2: B checks routing table: "F is my child"

Step 3: B forwards directly to F (downward)

Route: E -> B -> F (optimal)Advantages: - Efficient routing: Optimal paths (no detour through root) - Low latency: Direct routes between any nodes - Root not bottleneck: Distributed routing decisions

Disadvantages: - Memory overhead: Each node stores routing table - Scalability: Routing tables grow with network size - Updates: DAO messages for every node change

Best For: - Devices with sufficient memory (32+ KB RAM) - Networks requiring low latency - Point-to-point communication common

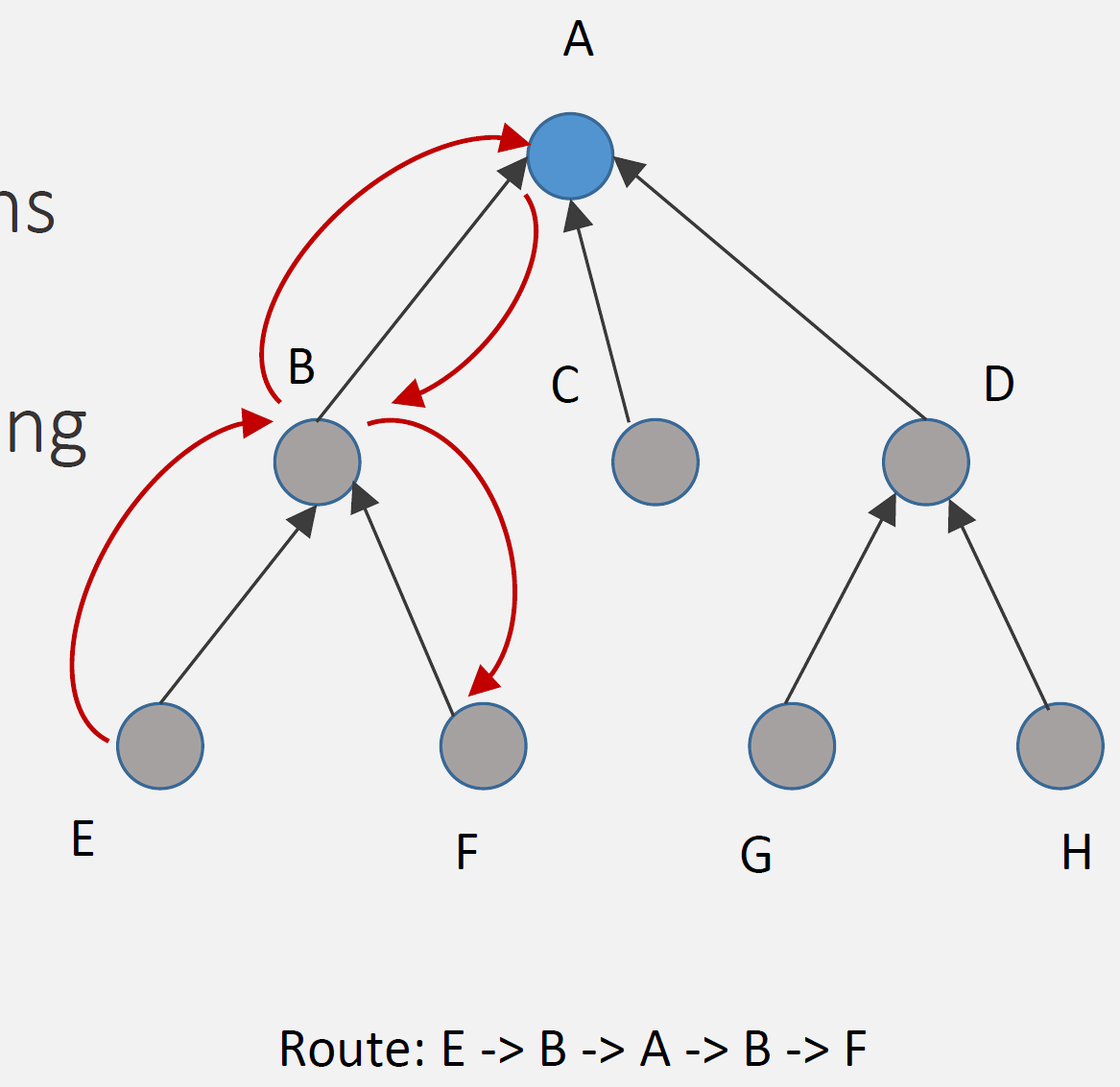

701.6.2 Non-Storing Mode

Only root maintains routing information; exploits source routing.

{fig-alt=“RPL Non-Storing mode showing centralized routing at ROOT with complete topology, intermediate nodes maintain only parent pointers, downward routing uses source routing headers from root”}

How It Works: 1. DAO to root: All nodes send DAO directly to root (upward) 2. Root stores all routes: Only root has complete routing table 3. Source routing: Root inserts complete path in packet header 4. Nodes forward: Follow instructions in packet header (no table lookup)

Example Route (E to F):

Step 1: E sends packet to parent B (upward, default route)

Step 2: B forwards to parent A (root) (upward, default route)

Step 3: A (root) checks routing table: "F via B"

Step 4: A inserts source route: [B, F]

Step 5: A sends to B with route in header

Step 6: B forwards to F following route

Route: E -> B -> A -> B -> F (via root)Advantages: - Low memory: Nodes don’t store routing tables (just parent) - Simple nodes: Minimal routing logic - Scalability: Network size doesn’t affect node memory

Disadvantages: - Suboptimal routes: All point-to-point traffic via root - Higher latency: Extra hops through root - Root bottleneck: All routing decisions at root - Header overhead: Source route in every packet

Best For: - Resource-constrained devices (< 16 KB RAM) - Primarily many-to-one traffic (sensors to gateway) - Point-to-point communication rare - Large networks (many nodes)

701.6.3 Storing vs Non-Storing Comparison

| Aspect | Storing Mode | Non-Storing Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Routing Table | Distributed (all nodes) | Centralized (root only) |

| Node Memory | Higher (routing table) | Lower (parent pointer only) |

| Route Optimality | Optimal (direct paths) | Suboptimal (via root) |

| Latency | Lower | Higher (extra hops) |

| Root Load | Low | High (all routing decisions) |

| Scalability | Limited by node memory | Limited by root capacity |

| DAO Destination | Parent | Root (through parents) |

| Header Overhead | Low | High (source routing) |

| Best For | Powerful nodes, low latency | Constrained nodes, many-to-one |

701.7 RPL Traffic Patterns

RPL optimizes for different traffic directions:

{fig-alt=“RPL traffic patterns: Many-to-One shows multiple sensors sending to gateway (upward routing), One-to-Many shows gateway sending to multiple actuators (downward), Point-to-Point shows direct sensor to actuator communication”}

701.7.1 Many-to-One (Upward Routing)

Pattern: Many sensors to Single gateway/root

How: - Each node knows parent (from DODAG construction) - Default route: Send to parent (toward root) - No routing table needed (upward)

Example: Temperature sensors reporting to cloud

Sensor 3 -> Node 1 -> Root -> Internet -> Cloud

(Upward along DODAG tree)Optimization: - Most common traffic in IoT (data collection) - Minimal state: Just parent pointer - Efficient: Direct path to root

701.7.2 One-to-Many (Downward Routing)

Pattern: Single controller to Many actuators

How: - Storing mode: Each node has routing table, forwards optimally - Non-storing mode: Root inserts source route, nodes follow

Example: Controller sends “turn off” to all lights

Root -> [Multicast or unicast to each light]Modes: - Storing: Root to Node 1 to Light 3 (optimal) - Non-storing: Root inserts route [Node 1, Light 3]

701.7.3 Point-to-Point (P2P)

Pattern: Sensor to Actuator (peer-to-peer)

How: - Upward then downward (via common ancestor, often root) - Storing mode: May find shorter path - Non-storing mode: Always via root

Example: Motion sensor triggers light

Storing: Sensor 3 -> Node 1 -> Light 4 (3 hops, if both under Node 1)

Non-Storing: Sensor 3 -> Node 1 -> Root -> Node 2 -> Light 4 (4 hops)701.8 Common Pitfalls

WarningCommon Pitfalls

1. Choosing the Wrong RPL Mode (Storing vs Non-Storing)

- Mistake: Using Storing mode on severely memory-constrained nodes (e.g., 2KB RAM sensors), causing routing table overflow and network instability when nodes cannot store routes to all descendants

- Why it happens: Storing mode provides more efficient point-to-point routing, so developers default to it without calculating memory requirements. Each routing entry requires ~20-40 bytes; a node with 50 descendants needs 1-2KB just for routing tables

- Solution: Calculate your network’s memory budget before choosing modes. Use Non-Storing mode when: (1) nodes have <8KB RAM, (2) network depth exceeds 4-5 hops, or (3) point-to-point traffic is rare. In Non-Storing mode, all downward routes go through the root, which must have sufficient memory but leaf nodes stay lightweight. For hybrid needs, consider using Storing mode only for nodes with adequate memory

2. Aggressive Trickle Timer Settings Causing Network Storms

- Mistake: Setting Trickle timer Imin too low (e.g., 100ms) or Imax too small (e.g., 4 doublings) in dense networks, causing constant DIO flooding that overwhelms the radio channel and drains batteries

- Why it happens: Developers test with small networks (3-5 nodes) where aggressive timers converge quickly. In production deployments with 50+ nodes, the same settings cause every node to transmit DIOs simultaneously during network events

- Solution: Start with conservative Trickle settings: Imin = 2-4 seconds, Imax = 16-20 doublings (giving maximum intervals of hours). For stable networks, RPL naturally reduces DIO frequency through Trickle’s exponential backoff. Only decrease timers if convergence time is unacceptable for your application. Monitor DIO message rates - if you see >1 DIO/minute/node in steady state, your Trickle parameters are too aggressive

3. Single DODAG Root Without Redundancy

- Mistake: Deploying production RPL networks with only one border router as the DODAG root, creating a single point of failure where root failure disconnects the entire network from the Internet

- Why it happens: RPL documentation focuses on single-root DODAGs for simplicity. Adding multiple roots requires understanding RPL instances, DODAG IDs, and root coordination, which adds deployment complexity

- Solution: For production deployments, configure multiple border routers with the same DODAG ID but different root preferences. Use RPL’s multiple DODAG instance feature to provide backup paths. Alternatively, deploy redundant roots with different DODAG IDs and configure important nodes to join both. Monitor root health and implement automatic failover scripts that promote a secondary root if the primary becomes unreachable

701.9 Visual Reference Gallery

NoteRPL and DODAG Visualizations

The following AI-generated diagrams provide additional perspectives on RPL routing concepts.

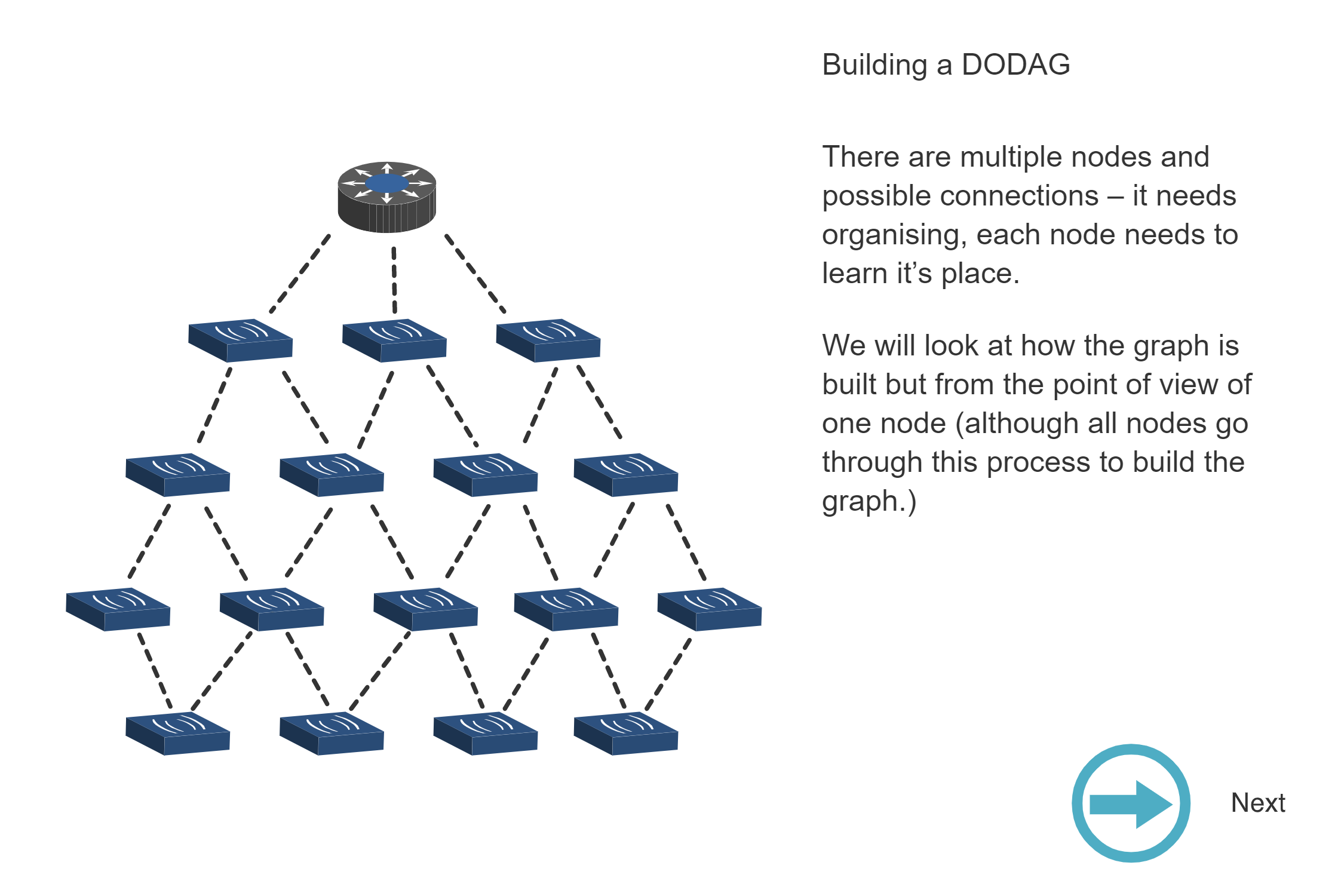

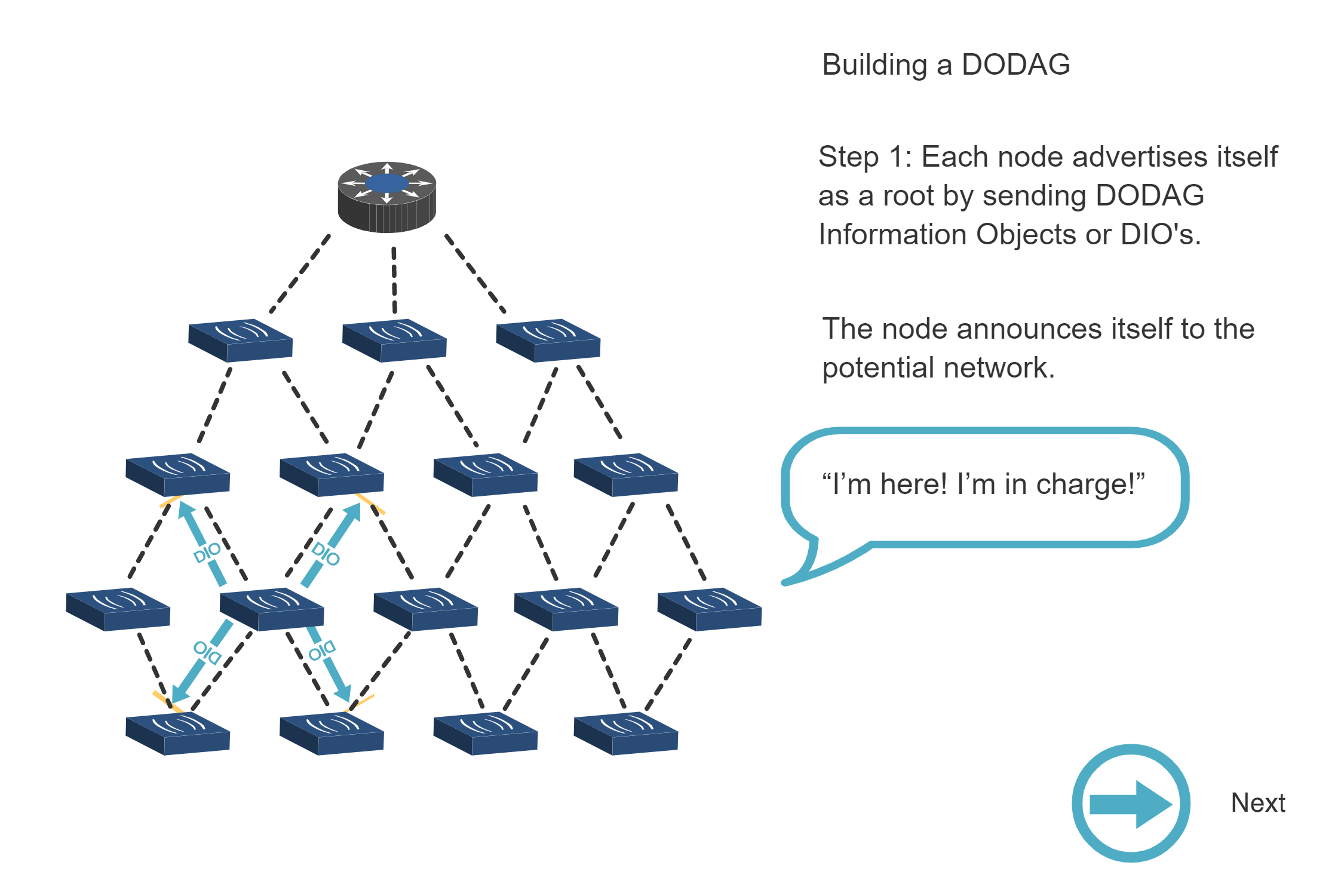

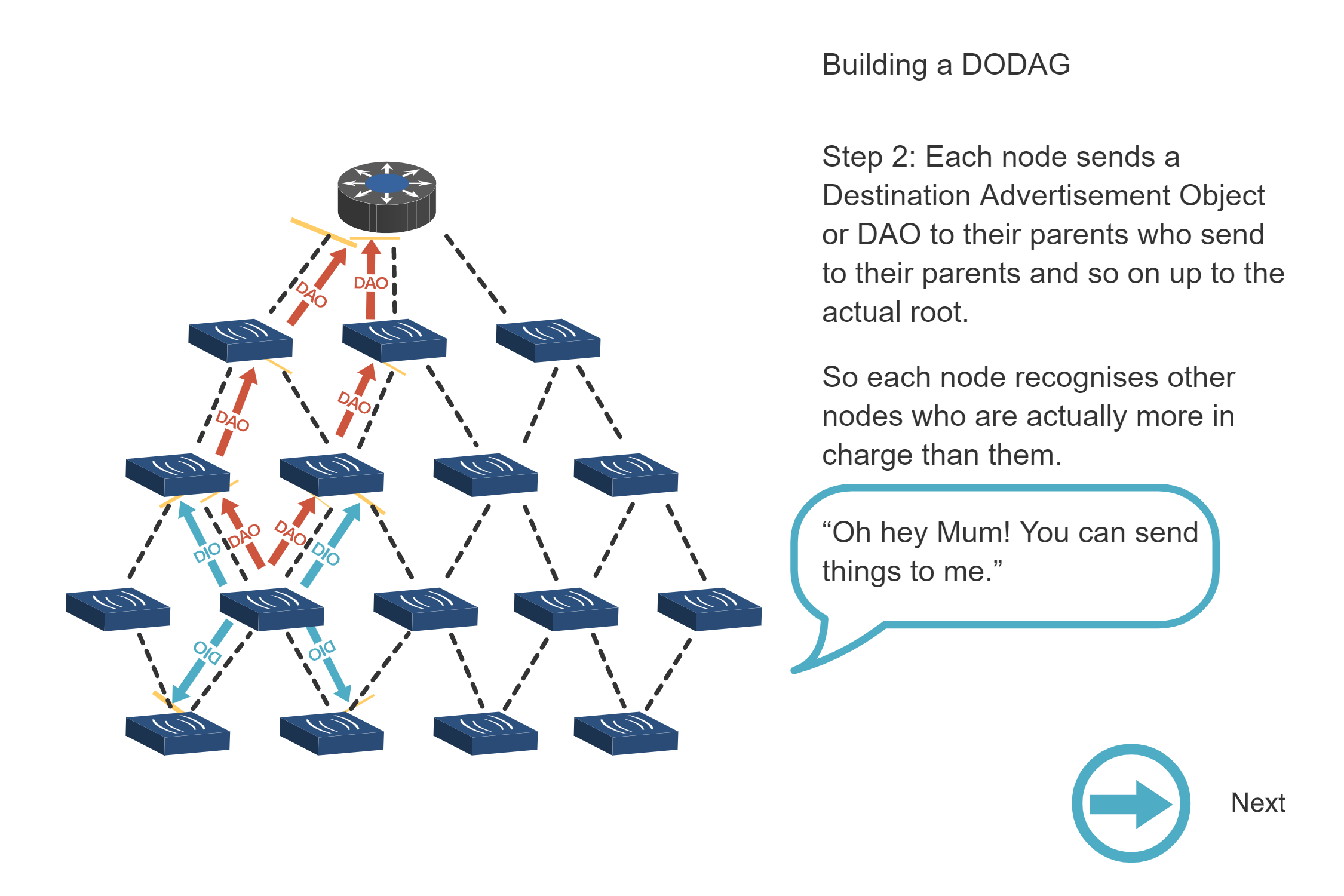

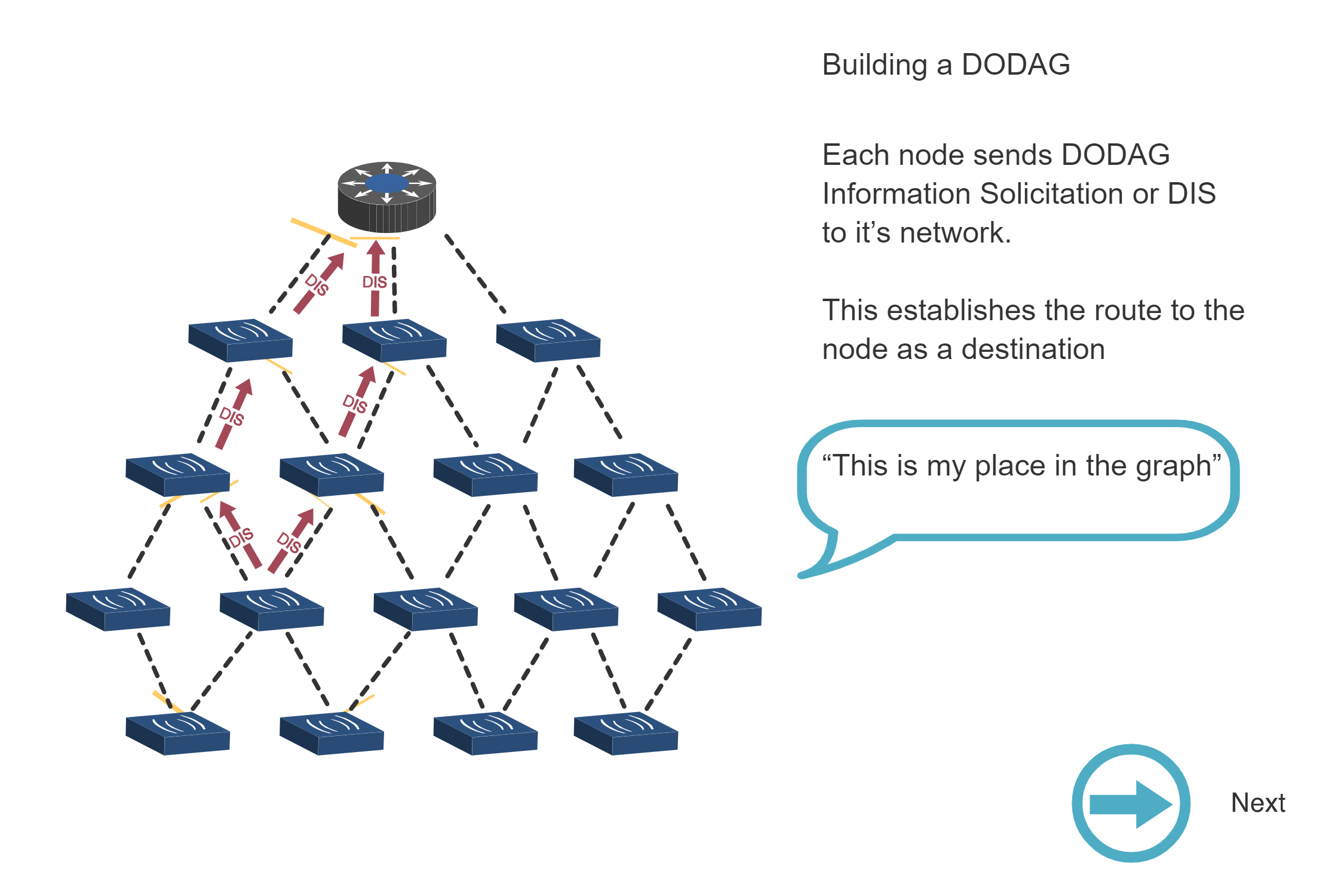

701.9.1 DODAG Construction Process

701.9.2 RPL Protocol Elements

701.9.3 DODAG Structure

701.9.4 Rank Computation

701.9.5 Applications

701.10 Original Source Figures (Alternative Views)

The following figures from the CP IoT System Design Guide provide alternative visual representations of RPL concepts covered in this chapter.

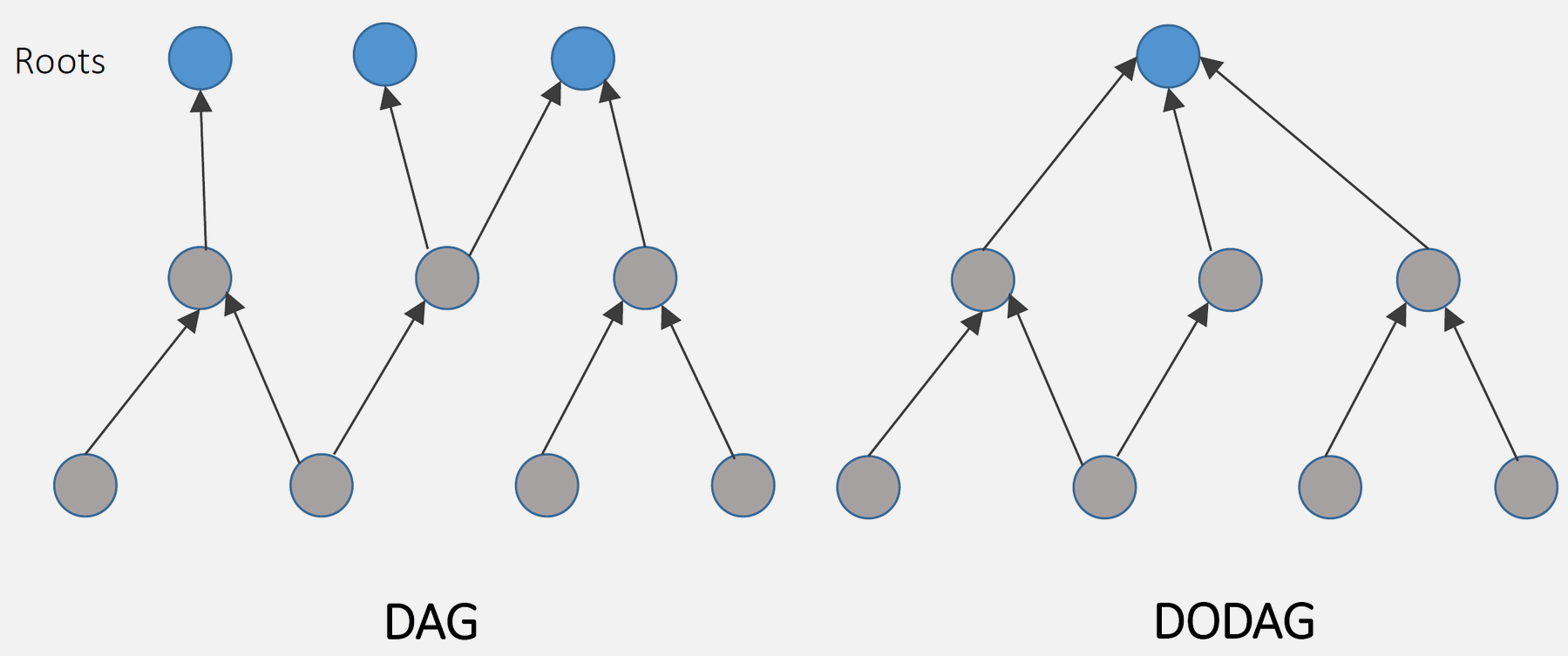

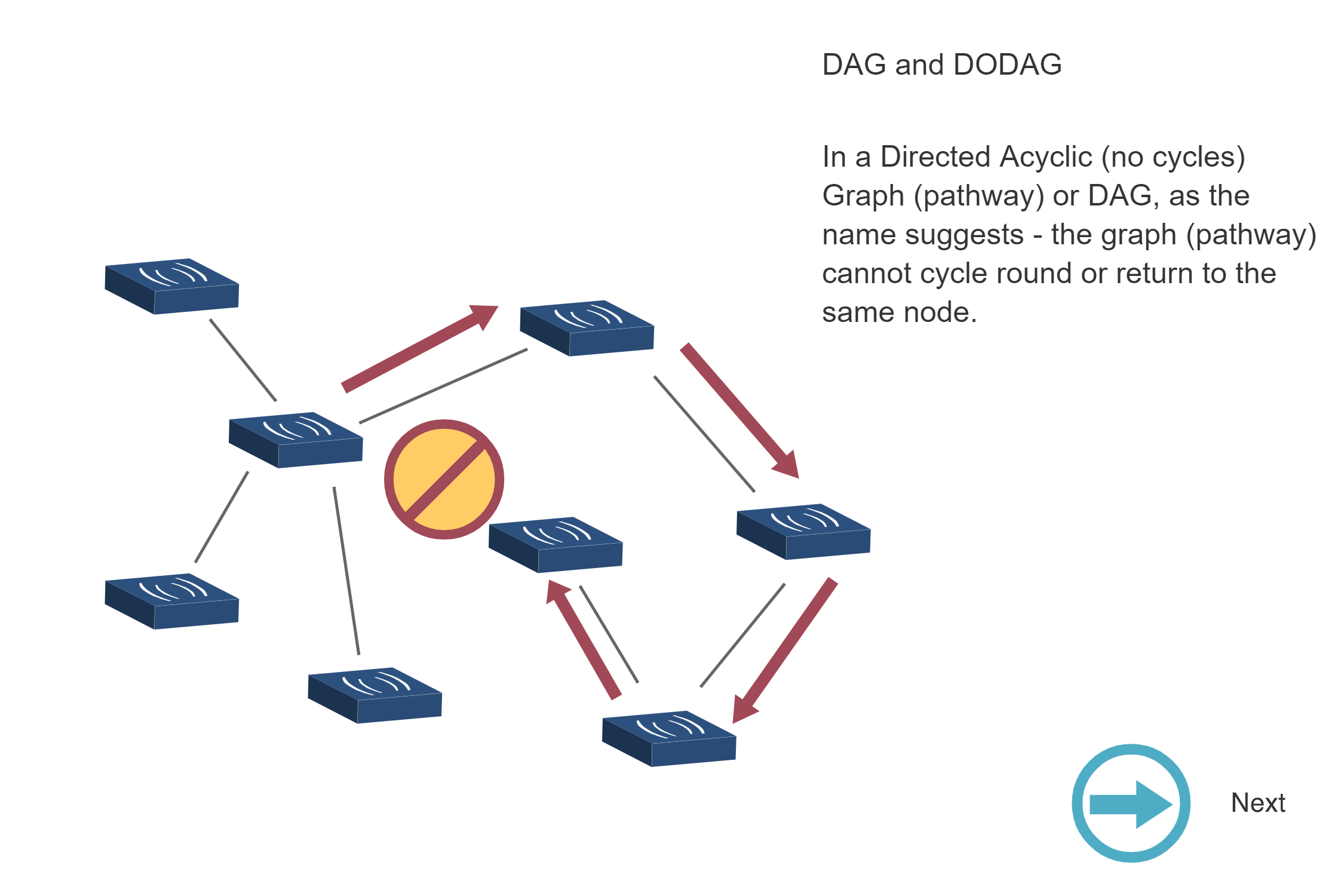

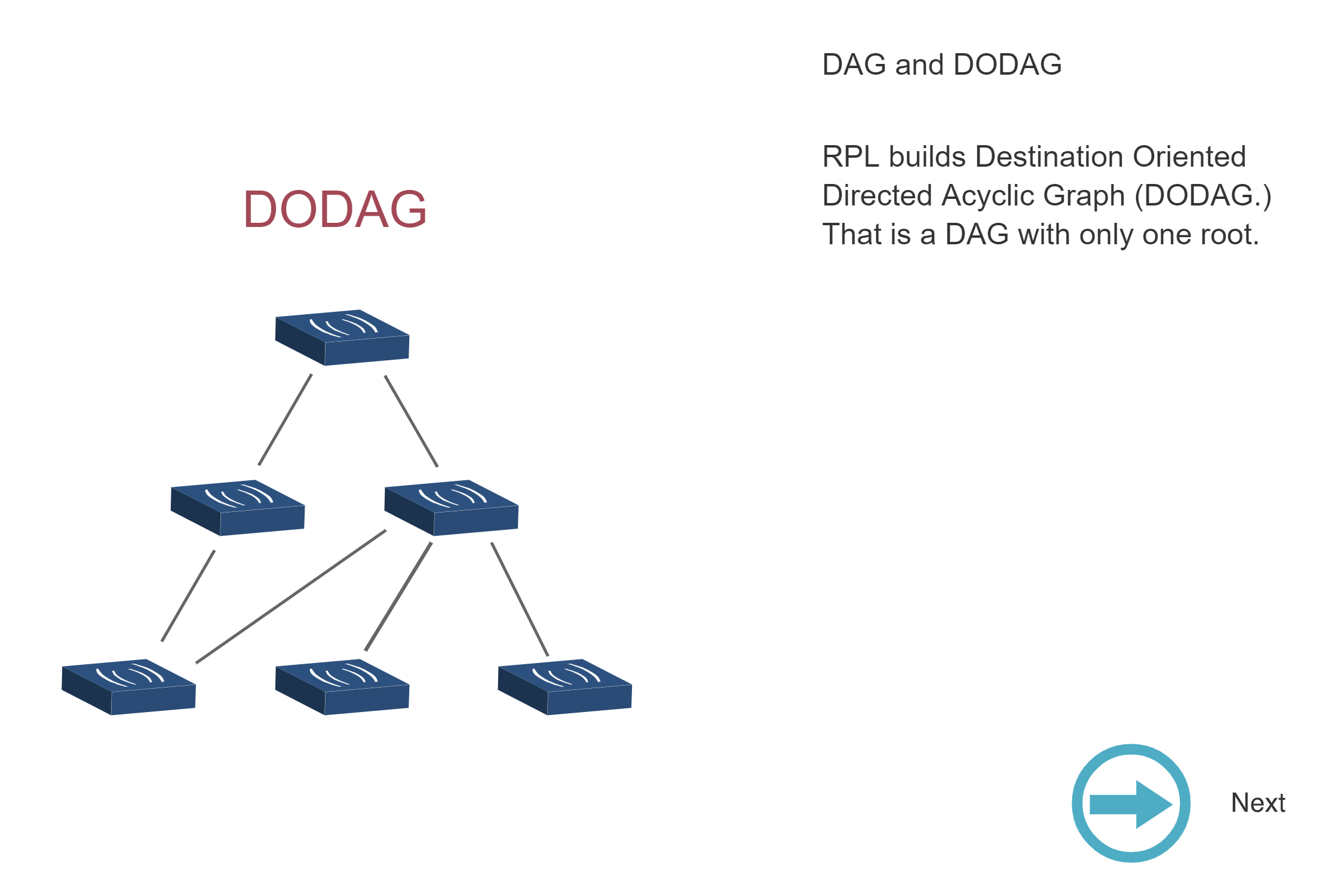

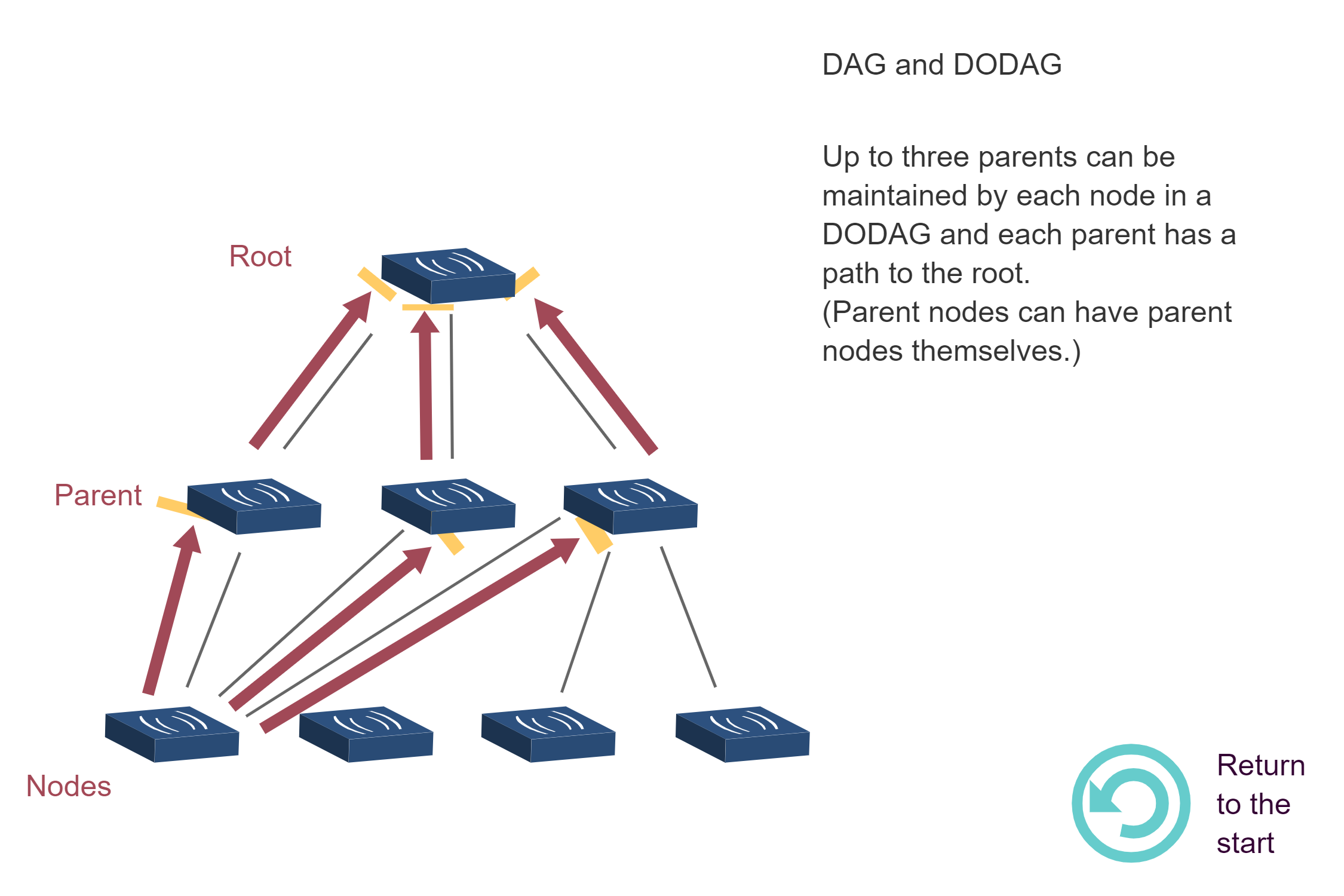

NoteDAG and DODAG Structures (Source Figure)

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 4 - Routing

NoteRPL DAG and DODAG Formation Sequence

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 4 - Routing

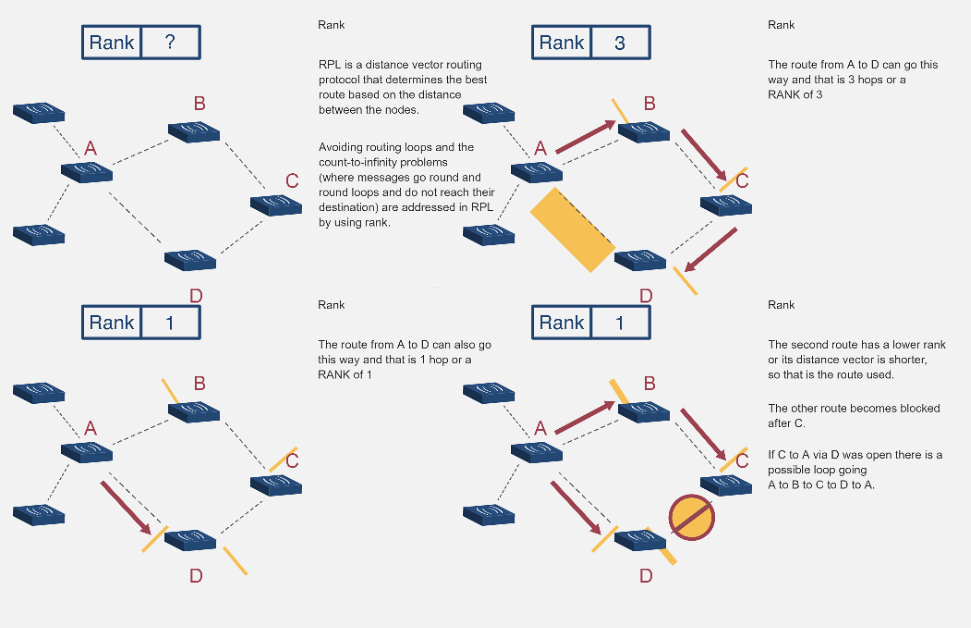

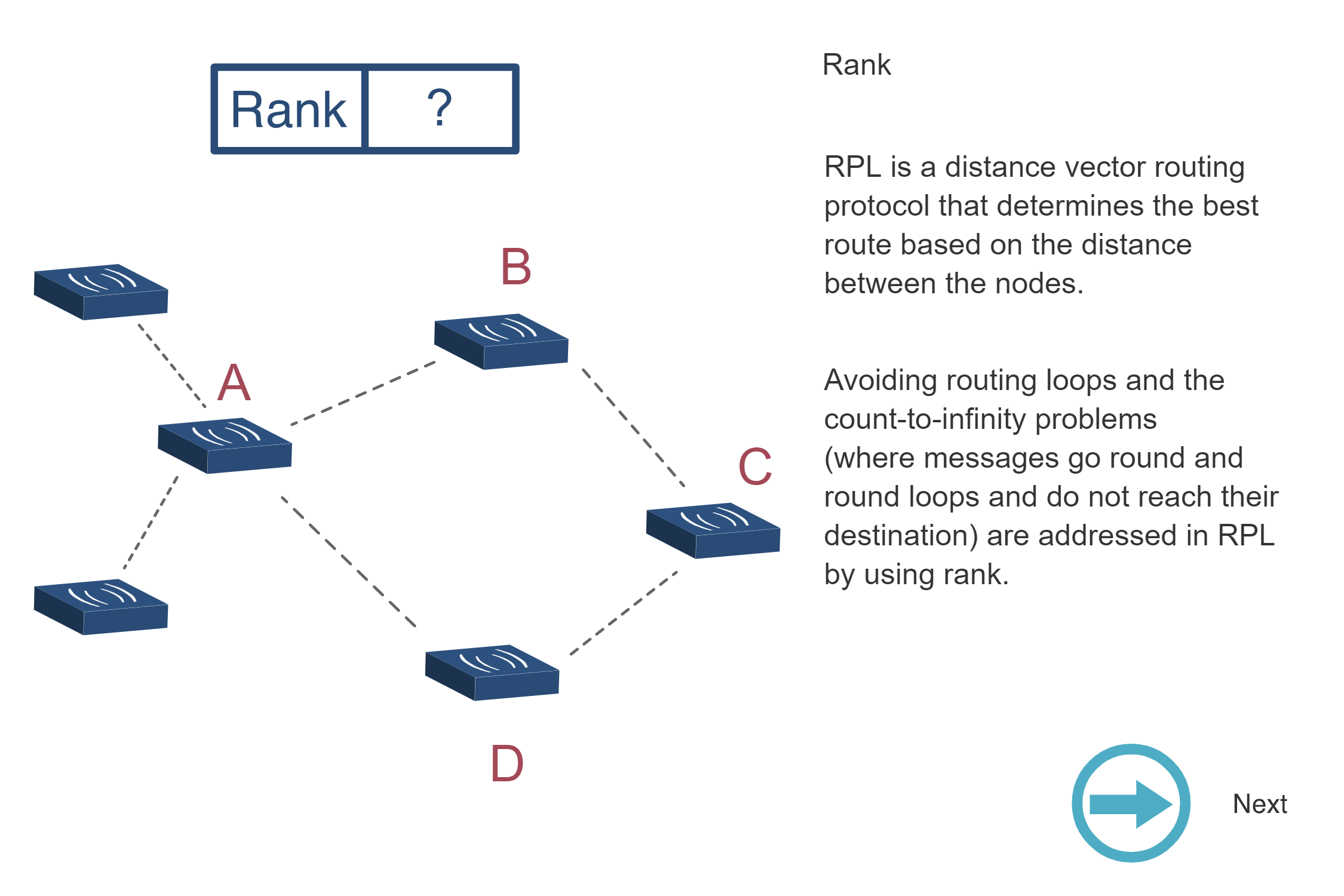

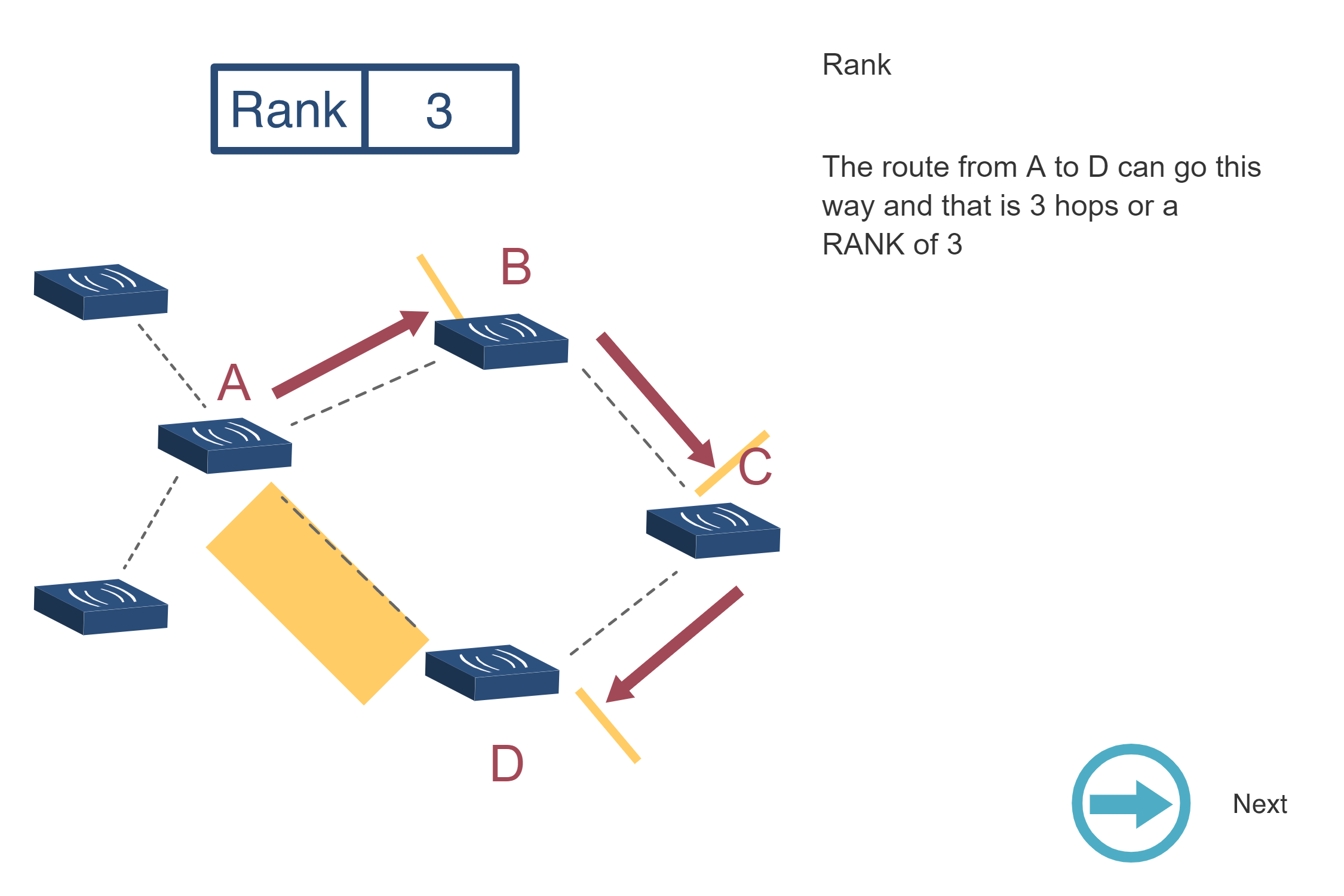

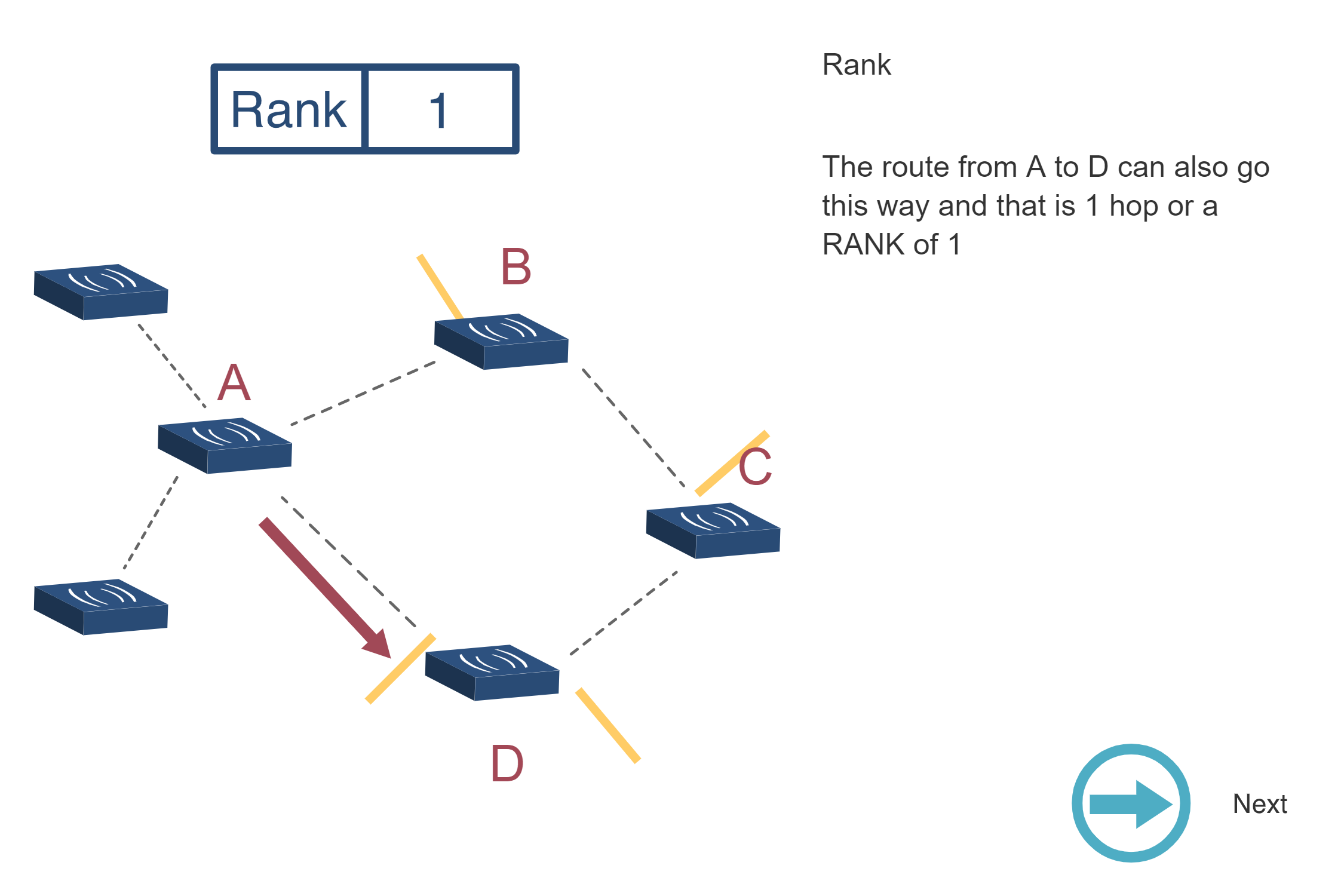

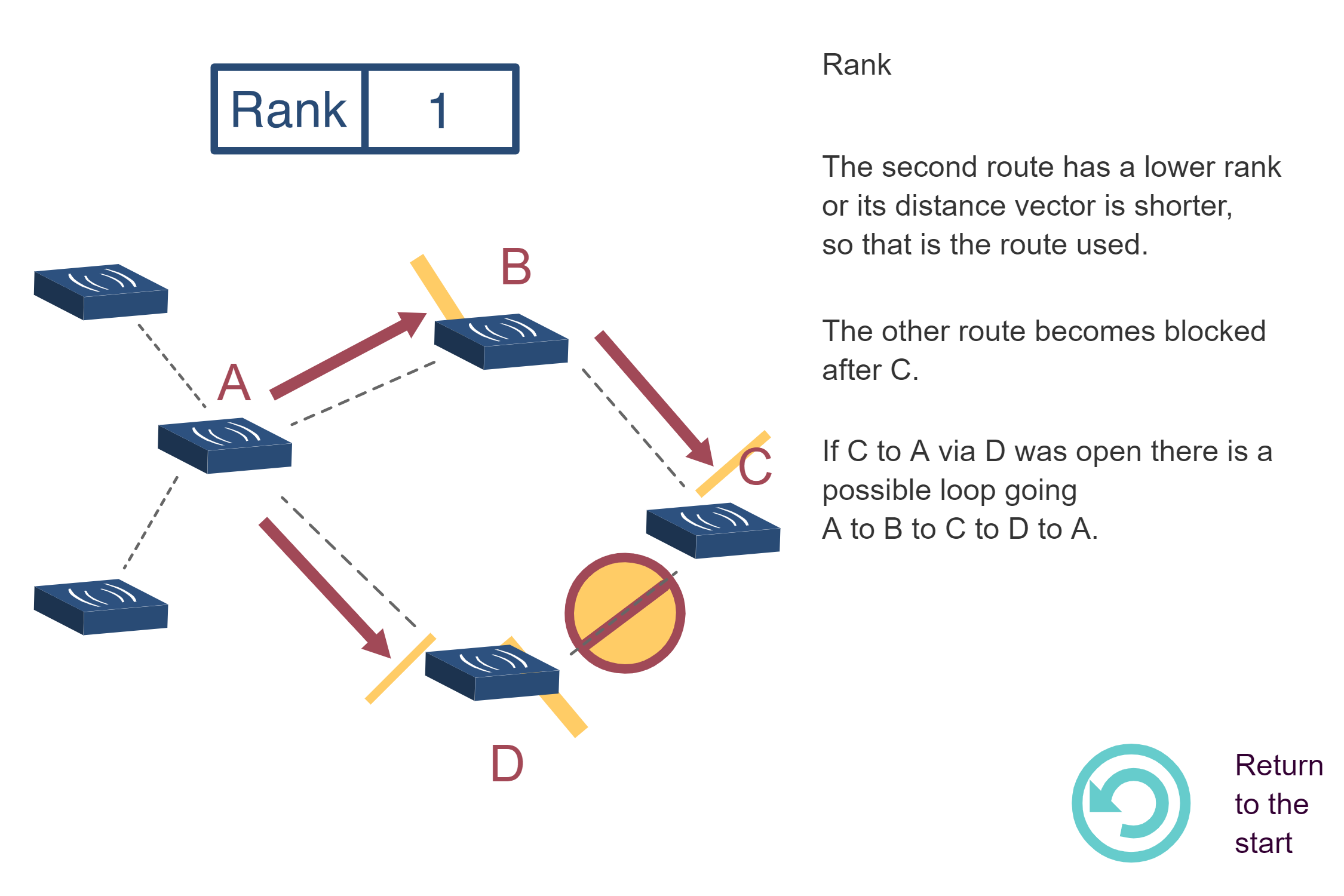

NoteRPL RANK Calculation Visualization

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 4 - Routing

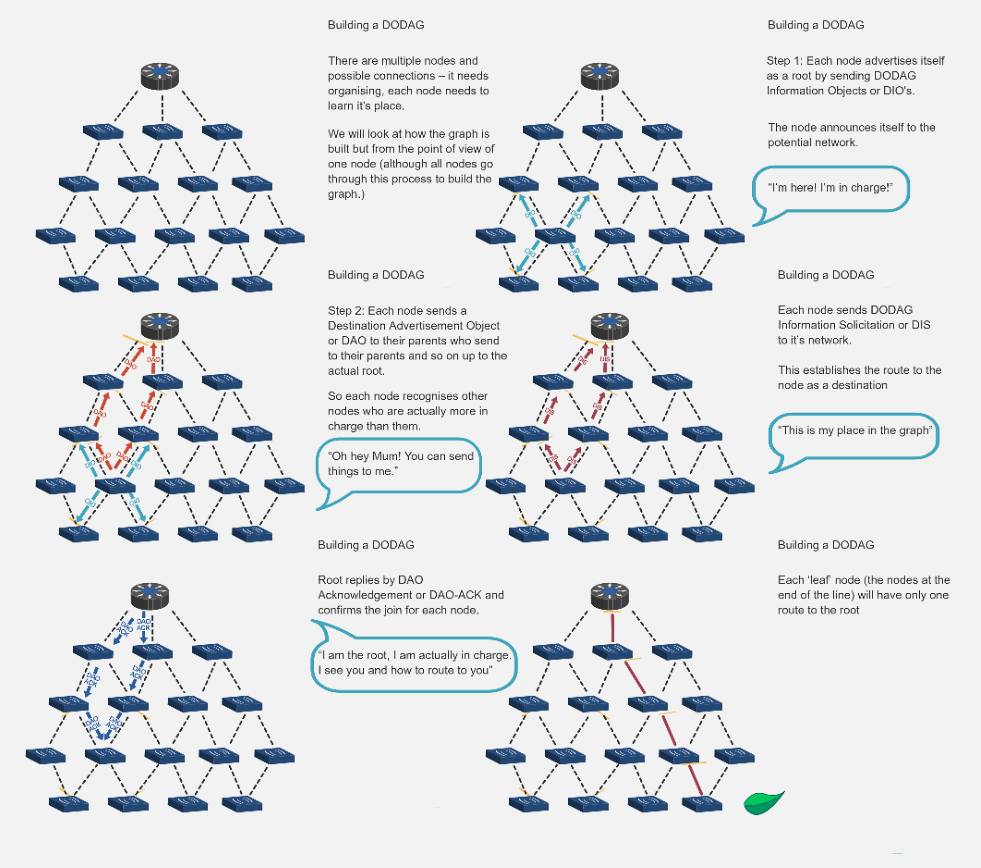

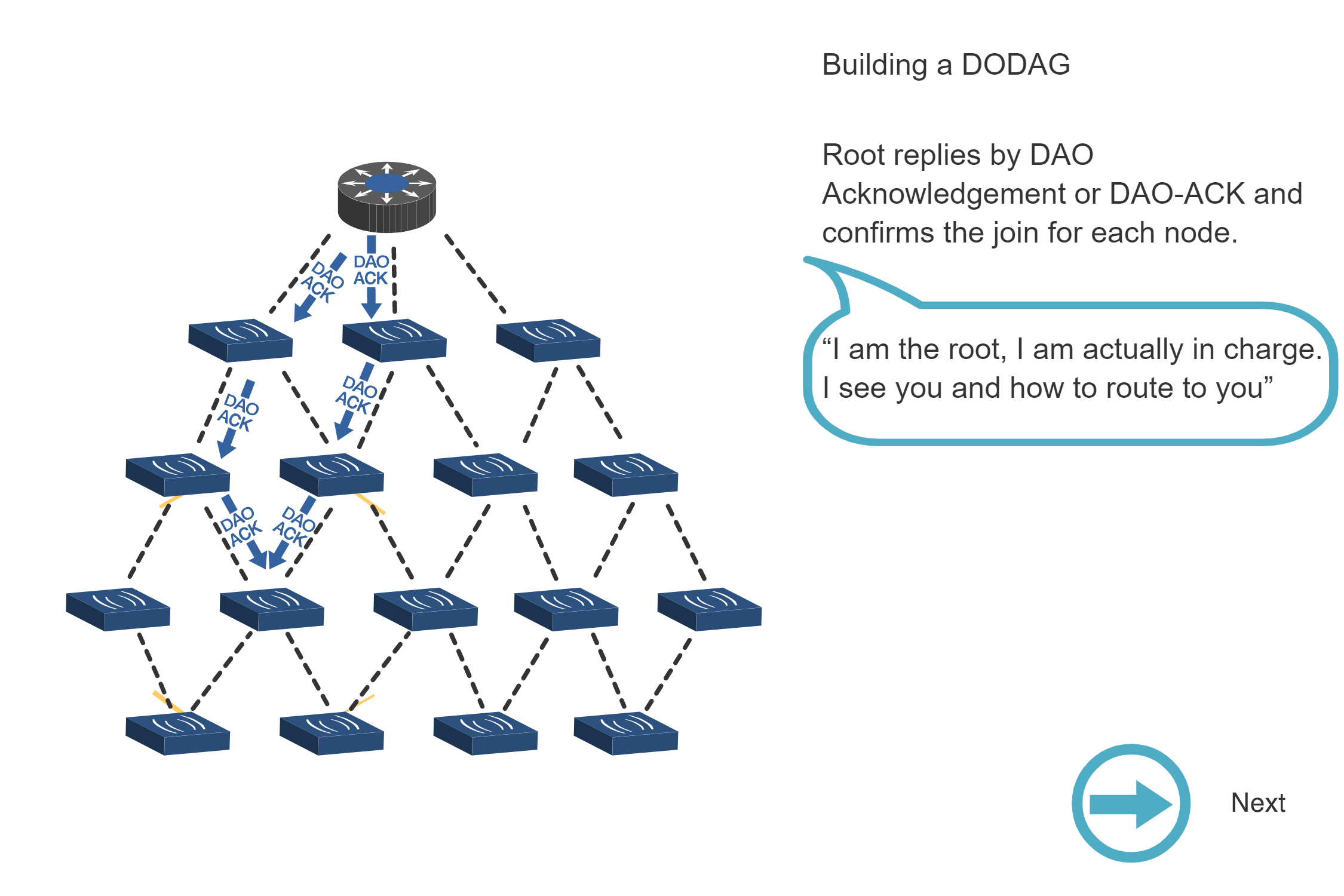

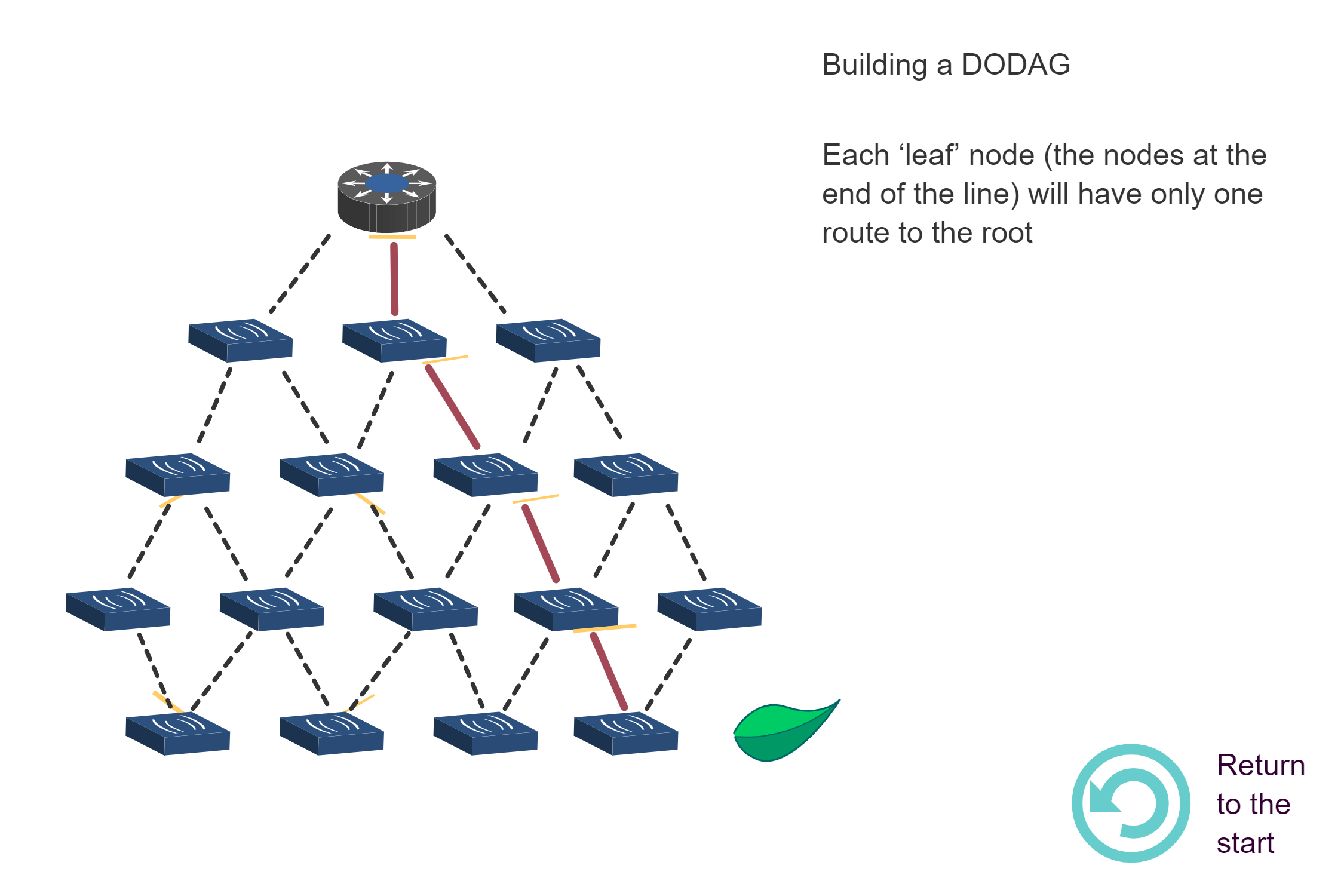

NoteBuilding a DODAG - Step-by-Step Process

Source: CP IoT System Design Guide, Chapter 4 - Routing

NoteInteractive: RPL DODAG Builder

Build and visualize an RPL DODAG (Destination Oriented Directed Acyclic Graph) interactively. Watch how nodes join the network, calculate their RANK based on different objective functions, and see DIO messages propagate through the tree.

Instructions:

- Click “Add Node” to add new nodes to the network

- Select different Objective Functions to see how RANK calculation changes

- Watch how each node selects its parent based on the objective function

- Observe the DIO propagation from root outward

- Use “Reset Network” to start fresh

Objective Function Details:

| Function | RANK Calculation | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Hop Count (OF0) | Parent RANK + 256 per hop | Simple networks, equal link quality |

| ETX | Parent RANK + (ETX x 256) | Lossy networks, reliability focus |

| Energy | Parent RANK + (Energy x 2) | Battery-powered, lifetime optimization |

Try This:

- Add 5-6 nodes and observe the tree structure

- Switch objective functions and reset - notice how the same nodes may select different parents

- Watch the orange DIO pulse showing message propagation

- Note how RANK increases as you move away from ROOT

701.11 Summary

This chapter covered the Trickle algorithm and RPL routing modes:

- Trickle Algorithm: Adaptive control message timing that achieves 99.7% reduction in DIO overhead through exponential backoff and instant reset on inconsistency

- Three Scenarios: Stable network (doubling interval), inconsistency (reset interval), insufficient redundancy (broadcast)

- Storing Mode: Distributed routing tables enable optimal paths but require more memory per node

- Non-Storing Mode: Centralized routing at root minimizes node memory but routes through root

- Traffic Patterns: Many-to-one (upward), one-to-many (downward), and point-to-point routing

- Common Pitfalls: Wrong mode selection, aggressive Trickle settings, single root without redundancy

701.12 What’s Next

Continue to RPL Labs and Quiz to apply your understanding through hands-on network design exercises and test your knowledge with comprehensive quiz questions.