%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ECF0F1', 'fontFamily': 'Inter, system-ui, sans-serif'}}}%%

graph TD

OPT["Optimization<br/>Trade-offs"] --> SPEED["Speed<br/>(Performance)"]

OPT --> SIZE["Size<br/>(Memory/Code)"]

OPT --> POWER["Power<br/>(Dissipation)"]

OPT --> ENERGY["Energy<br/>(Battery Life)"]

SPEED -.->|Conflicts| SIZE

SPEED -.->|Conflicts| ENERGY

SIZE -.->|Conflicts| SPEED

POWER -.->|Conflicts| SPEED

style OPT fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style SPEED fill:#E74C3C,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style SIZE fill:#3498DB,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style POWER fill:#F39C12,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style ENERGY fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

1621 Optimization Fundamentals and Trade-offs

1621.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Define optimization in the context of IoT systems and understand why it matters

- Identify the four key optimization dimensions: speed, size, power, and energy

- Analyze trade-offs between competing optimization goals

- Select appropriate optimization priorities based on application requirements

- Avoid common optimization mistakes including premature optimization

1621.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- Embedded Systems Programming: Understanding firmware development and microcontroller architectures

- Sensor Fundamentals: Knowledge of sensor power consumption provides context for energy optimization

Think of optimization like packing a suitcase for a long trip—you want to fit the most important items while keeping the bag light.

In IoT, your “suitcase” is limited: tiny memory, slow processors, and batteries that need to last years. Optimization is the art of making your code and hardware do more with less.

Two types of optimization:

| Type | What You’re Improving | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Energy, power, heat | Make sensor sleep more, transmit less |

| Software | Speed, memory | Use smaller data types, avoid loops |

Why optimization matters in IoT:

| Resource | Desktop Computer | IoT Device |

|---|---|---|

| RAM | 16 GB | 256 KB (65,000x less!) |

| CPU | 3 GHz | 80 MHz (40x slower) |

| Power | 500 watts | 0.001 watts |

| Battery | N/A | Must last 5+ years |

Common optimization techniques:

- Loop unrolling — Instead of looping 100 times, write out 4 iterations at once (faster, but bigger code)

- Function inlining — Put tiny function code directly where it’s called (saves overhead)

- Fixed-point math — Use integers instead of decimals (much faster on small processors)

- Sleep modes — Put the chip to sleep between readings (saves battery)

The trade-off triangle:

Speed

/\

/ \

/ \

/______\

Size Power

You can optimize for two, but often sacrifice the third!Real-world example: - Original code: Reads sensor every 1 second, always awake -> Battery lasts 2 days - Optimized: Reads every 10 seconds, sleeps between readings -> Battery lasts 6 months!

Key insight: In IoT, “good enough” code that runs for years beats “perfect” code that drains the battery in a week.

1621.3 What is Optimisation?

Optimisation: Modifying some aspect of a system to make it run more efficiently, or utilize less resources.

- Optimising Hardware: Making it use less energy, or dissipate less power

- Optimising Software: Making it run faster, or use less memory

1621.3.1 Advanced Optimization Visualizations

The following AI-generated visualizations illustrate key optimization techniques and concepts for IoT system development.

1621.4 Optimisation Choices

This view helps select optimization priorities based on your specific IoT application:

%% fig-alt: "Optimization priority matrix by IoT application type. Industrial control prioritizes speed and reliability over size. Wearables prioritize energy and size over speed. Environmental monitoring prioritizes energy over everything else. Gateway devices prioritize speed and size. Each application type has different optimal trade-off points."

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ECF0F1'}}}%%

flowchart TD

App[Application Type] --> Industrial["Industrial Control<br/>Priority: SPEED<br/>Latency < 10ms<br/>Energy: mains-powered"]

App --> Wearable["Wearables<br/>Priority: SIZE + ENERGY<br/>Must fit tiny package<br/>Days battery life"]

App --> EnvMon["Environmental Sensor<br/>Priority: ENERGY<br/>Years battery life<br/>Slow updates OK"]

App --> Gateway["Edge Gateway<br/>Priority: SPEED + SIZE<br/>Process many streams<br/>Limited RAM/Flash"]

Industrial --> Opt1["Use -O3, inline,<br/>hardware interrupts"]

Wearable --> Opt2["Use -Os, sleep modes,<br/>minimal libraries"]

EnvMon --> Opt3["Max duty cycle,<br/>batch transmissions"]

Gateway --> Opt4["Streaming buffers,<br/>avoid heap alloc"]

style App fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style Industrial fill:#E74C3C,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Wearable fill:#3498DB,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style EnvMon fill:#27AE60,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

style Gateway fill:#E67E22,stroke:#2C3E50,color:#fff

Your application type determines which optimization trade-offs make sense.

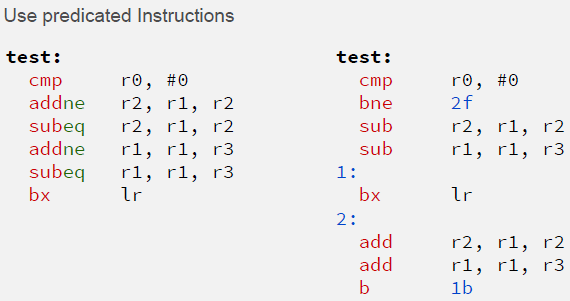

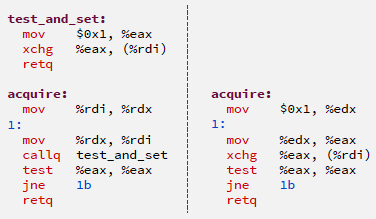

{fig-alt=“Optimization trade-off diagram showing four competing objectives: speed/performance, code/memory size, power dissipation, and energy/battery life with conflicting relationships indicated by dotted lines”}

Key Questions: - Optimise for speed? Do we need to react to events quickly? - Optimise for size? Are we memory/space constrained? - Optimise for power? Is there limited scope for power dissipation? - Optimise for energy? Do we need to conserve as much energy as possible?

Usually requires some combination (with trade-off) of all of these!

The Misconception: Many developers believe that optimizing for speed (-O3 compiler flag, aggressive loop unrolling, SIMD vectorization) automatically reduces power consumption because the processor finishes work faster and can sleep sooner. This leads to choosing speed-focused optimizations for battery-powered IoT devices.

Why It’s Wrong (With Numbers): Power consumption = Voltage^2 x Capacitance x Frequency. Faster code often requires: - Higher clock frequency (80 MHz -> 200 MHz = 2.5x power for 2x speed) - More parallel execution units (SIMD uses 4x ALUs = 3x power draw during execution) - Larger code size (-O3 generates 1.5-2x more instructions = more instruction fetches = more memory power)

Real-World Example: Consider a temperature sensor reading every 10 seconds: - Baseline (-O2): 18ms processing @ 80 MHz, sleep 9,982ms -> Average power: 5 mW active + 0.01 mW sleep = 0.019 mW average - Speed Optimized (-O3 + 200 MHz): 6ms processing @ 200 MHz (12 mW active), sleep 9,994ms -> Average power: 12 mW active + 0.01 mW sleep = 0.017 mW average - Size/Energy Optimized (-Os + sleep): 22ms processing @ 80 MHz, sleep 9,978ms -> Average power: 5 mW active + 0.01 mW sleep = 0.020 mW average

The Surprise: Speed optimization saved only 10% power (0.019 -> 0.017 mW) because sleep time dominates (99.8% of cycle time). The 12ms time savings (18ms -> 6ms) is irrelevant when sleeping 9,982ms! Meanwhile, -O3’s larger code size increased flash memory by 38% (52 KB -> 72 KB), requiring more expensive hardware.

The Correct Approach: For duty-cycled IoT devices, optimize sleep time, not active time: - Sleep deeper: Change sleep mode from 10 uA to 1 uA = 10x power savings (far exceeds any -O3 benefit) - Sleep longer: Reduce sensor sampling rate 1s -> 10s = 10x battery life (if application permits) - Optimize for size: Use -Os to minimize flash/RAM -> enables cheaper MCUs with smaller batteries

When Speed DOES Save Power: Speed optimization helps when the device cannot sleep during processing: - Real-time audio/video processing (continuous operation) - Safety-critical systems (must respond within deadline) - Compute-bound tasks preventing sleep (e.g., cryptography taking >1 second)

Key Principle from Chapter: “Optimise for energy? Do we need to conserve as much energy as possible?” For battery-powered IoT, the answer is optimize for longest sleep time, not fastest execution. The chapter shows: flash memory dominates die area (27.3 mm^2 vs 0.43 mm^2 for CPU)—choosing -Os over -O3 saves both energy AND cost by enabling smaller flash chips.

Quantitative Decision Rule: If sleep time > 100x active time, optimize for code size/sleep depth. If active time > 10% of cycle time, then consider speed optimization. For typical IoT sensors (0.1-1% duty cycle), speed optimization provides <1% battery life improvement.

A classic mistake is optimizing code before measuring where bottlenecks actually are. Developers spend days hand-optimizing assembly or complex bit manipulations in functions that consume 0.1% of total execution time, while ignoring the inefficient algorithm consuming 80% of CPU. Example: A team spent 2 weeks optimizing sensor reading code (saving 5ms per hour) but never profiled their JSON parsing library that consumed 2 seconds per message. Rule: Always profile first - use actual measurements to identify hotspots. The 80-20 rule applies: 80% of execution time typically comes from 20% of code. Focus optimization efforts on measured bottlenecks, not assumptions. Start with algorithmic improvements (O(n^2) to O(n log n)), then compiler flags, then micro-optimizations only if needed.

Option A (Active Power Gating): MOSFET switch cuts power to sensors/peripherals when idle, achieves true zero leakage (<0.1 uA), requires GPIO pin + MOSFET ($0.05-0.20), adds 1-10 ms startup delay for sensor stabilization, potential for inrush current damage if not managed

Option B (Continuous Low-Power Mode): Peripherals remain powered but in ultra-low-power standby, typical standby current 1-50 uA per peripheral, instant readiness (<1 us), no external components, stable sensor calibration maintained

Decision Factors: Choose power gating for sensors with high standby current (>100 uA) or rarely used peripherals (GPS module at 20 mA idle - gate it!), deployments where every microamp matters for 10+ year battery life. Choose continuous low-power for frequently accessed sensors (accelerometer at 6 uA standby, sampled 10x/second - gating overhead exceeds savings), temperature-sensitive sensors requiring thermal stabilization (10-second warmup wastes more energy than continuous 5 uA), or when GPIO pins are scarce. Quantified example: A humidity sensor drawing 50 uA standby, read every 60 seconds: Continuous = 50 uA x 60s = 3 mAs/cycle. Power-gated = 0 uA x 59s + 2mA x 500ms warmup = 1 mAs/cycle - 3x better. But for 1-second reads: Continuous = 0.05 mAs, Power-gated = 1 mAs - continuous wins by 20x.

Option A (-Os Size Optimization): Minimizes code size (20-40% smaller than -O3), moderate compile time, fits in smaller/cheaper flash (32 KB vs 64 KB saves $0.30-1.00/unit), reduced instruction cache misses, slightly slower execution (10-30% vs -O3), better for I/O-bound code

Option B (-O3 Speed Optimization): Maximum execution speed through aggressive inlining and loop unrolling, larger code size (1.5-2x vs -Os), may exceed flash capacity on small MCUs, faster compile-intensive algorithms, risk of code size exceeding instruction cache causing performance regression

Decision Factors: Choose -Os for flash-constrained MCUs (STM32L0 with 32KB, ATtiny with 8KB), battery-powered devices where code fetches from flash cost energy (1-5 pJ/bit), networking/protocol stacks where code size dominates, and production cost optimization at scale (10K units x $0.50 flash savings = $5,000). Choose -O3 for compute-intensive DSP/ML on edge (audio processing, anomaly detection), latency-critical control loops (motor control, PID), and devices with abundant flash (ESP32 with 4MB). Quantified example: A 45 KB -O3 binary vs 28 KB -Os binary - the -Os version fits in a 32 KB STM32L011 ($0.80) instead of requiring 64 KB STM32L031 ($1.30), saving $0.50/unit at 15% performance cost. For 50,000 units, that’s $25,000 saved - worth the 3ms extra processing time per sensor read.

1621.5 Knowledge Check

Scenario: Your battery-powered IoT sensor has 128 KB flash (80% full after -O2 compile) and runs on a 16 MHz ARM Cortex-M0+ processor. Current firmware processes sensor data in 45ms, transmits results via LoRaWAN (200ms), then sleeps for 10 minutes. You’re evaluating -O3 (code increases to 110 KB, processing drops to 30ms) vs. -Os (code shrinks to 65 KB, processing increases to 55ms).

Think about: 1. Which optimization flag should you choose and why? 2. How much does the 15ms processing time difference (45ms -> 30ms with -O3) affect battery life? 3. What’s the real benefit of reclaiming 25 KB flash with -Os?

Key Insight: Choose -Os. The 15ms processing time improvement from -O3 is irrelevant for battery life—the sensor sleeps 10 minutes (600,000ms) between readings. Active time is 45ms + 200ms = 245ms per cycle. Reducing to 30ms + 200ms = 230ms saves only 15ms/600,000ms = 0.0025% energy savings—negligible. Meanwhile, -Os frees 25 KB flash (128 KB -> 103 KB = 20% reduction), enabling: (1) future firmware updates, (2) data buffering during network outages, (3) additional features without hardware redesign. For duty-cycled IoT devices, code size matters more than processing speed when active time is tiny compared to sleep time. Exception: If processing exceeded 10 minutes, preventing timely readings, then -O3’s speed would matter. The chapter’s guidance: “Optimise for energy? Do we need to conserve as much energy as possible?”—here, sleep time dominates, so optimize for flash (future flexibility).

1621.6 Summary

Optimization fundamentals establish the foundation for efficient IoT systems:

- Four Dimensions: Speed, size, power, and energy often conflict—you must prioritize

- Application-Driven: Industrial control needs speed; environmental sensors need energy efficiency

- Avoid Premature Optimization: Profile first, optimize the actual bottleneck

- Trade-off Analysis: Quantify benefits before choosing optimization strategies

- Sleep Dominates: For duty-cycled devices, sleep efficiency matters more than processing speed

The key is understanding your application requirements and choosing appropriate optimization strategies with full awareness of trade-offs.

1621.7 What’s Next

The next chapter covers Hardware Optimization, which explores processor selection from DSPs to ASICs, heterogeneous multicore architectures like ARM big.LITTLE, and hardware acceleration strategies for IoT applications.