%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '15px'}}}%%

graph TB

SP["Setpoint"] --> Error["Error<br/>Calculation<br/>(SP - PV)"]

PV["Process<br/>Variable<br/>(Measured)"] --> Error

Error --> P["P Term:<br/>Kp × error<br/>(Current Error)"]

Error --> I["I Term:<br/>Ki × ∫error dt<br/>(Accumulated)"]

Error --> D["D Term:<br/>Kd × d(error)/dt<br/>(Rate of Change)"]

P --> Sum["Σ<br/>Sum"]

I --> Sum

D --> Sum

Sum -->|Control Signal| Plant["Process/<br/>Plant"]

Plant -->|Output| PV

style Error fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style P fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style I fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style D fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Sum fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style Plant fill:#7F8C8D,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

232 PID Control Fundamentals

232.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain the three components of a PID controller (Proportional, Integral, Derivative)

- Define and calculate error in feedback control systems

- Understand how proportional control responds to current error magnitude

- Identify the limitations of proportional-only control

- Apply the PID equation to calculate controller output

232.2 PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) Control

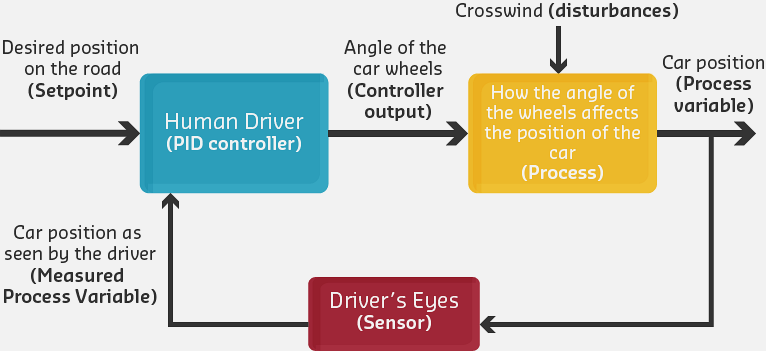

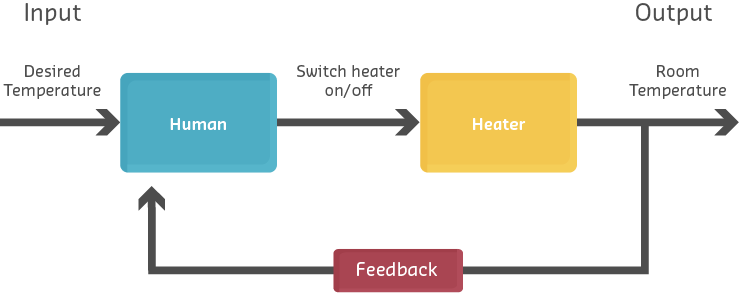

While simple closed-loop systems provide basic feedback, achieving optimal performance often requires more sophisticated control algorithms. The PID controller is the most widely used feedback control algorithm in industrial and IoT applications.

232.2.1 PID Overview

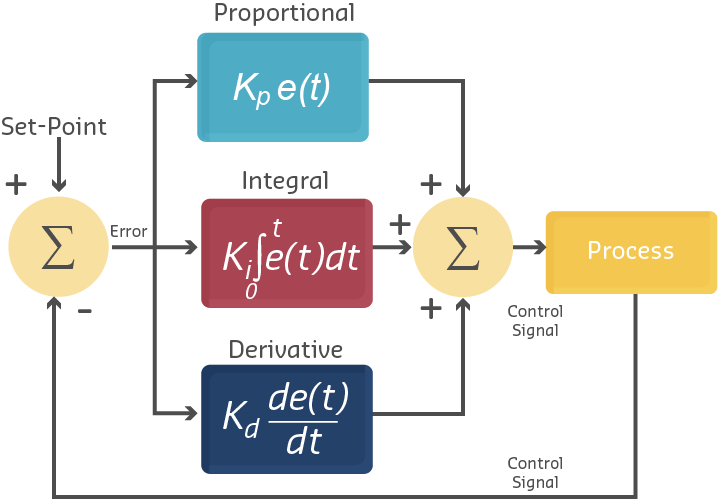

A PID controller uses three different control strategies simultaneously, each addressing different aspects of error correction:

- P (Proportional): Reacts to current error magnitude

- I (Integral): Reacts to accumulated error over time

- D (Derivative): Reacts to rate of error change

Imagine you’re driving on a highway and need to change lanes. Your brain performs PID control naturally:

232.2.2 Proportional (P) - React to the Error

- Situation: You’re 2 feet from where you want to be

- Response: Turn the steering wheel proportionally - bigger error = bigger turn

- Problem: If you only use P, you’ll overshoot and oscillate!

232.2.3 Integral (I) - Eliminate Steady-State Error

- Situation: A crosswind keeps pushing you right

- Response: You notice you’re always a bit off, so you hold the wheel slightly left

- The I term accumulates past errors and corrects persistent bias

- Real IoT example: Temperature sensor with consistent 0.5C offset

232.2.4 Derivative (D) - Anticipate and Dampen

- Situation: You’re approaching your target lane fast

- Response: You start turning back before you reach it to avoid overshooting

- The D term predicts future error based on rate of change

- Real IoT example: Slowing down a motor before it hits the target position

232.2.5 The Complete Picture

| Term | Responds To | Fixes | Danger If Too High |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | Current error | Immediate deviation | Oscillation |

| I | Accumulated error | Persistent bias | Overshoot, instability |

| D | Rate of change | Overshoot | Noise amplification |

Key insight: Most IoT control uses PI (no derivative) because sensor noise makes D unstable. Only use D when you have clean, high-frequency data!

PID Controller Block Diagram: Error signal splits into three parallel paths. P term responds to current error, I term accumulates past errors, D term predicts future based on rate of change. All three combine to produce optimal control signal.

PID Equation:

\[ u(t) = K_p \cdot e(t) + K_i \cdot \int_{0}^{t} e(\tau) \, d\tau + K_d \cdot \frac{de(t)}{dt} \]

Where: - \(u(t)\) = Controller output at time \(t\) - \(e(t)\) = Error (Set Point - Process Variable) - \(K_p\) = Proportional gain - \(K_i\) = Integral gain - \(K_d\) = Derivative gain

Common PID Combinations:

| Mode | Usage | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| P | Sometimes | Simple temperature control, LED brightness |

| PI | Most common | HVAC systems, level control, pressure regulation |

| PID | Sometimes | Motor speed control, precision positioning |

| PD | Rare | Servo motors, fast response systems |

232.3 Understanding Error in PID Control

The foundation of PID control is the error signal:

- Process Variable (PV):

- The actual measured value of what we’re controlling (e.g., current temperature)

- Set Point (SP):

- The desired target value (e.g., target temperature)

- Error (e):

- The difference between desired and actual values

\[ e(t) = SP - PV(t) \]

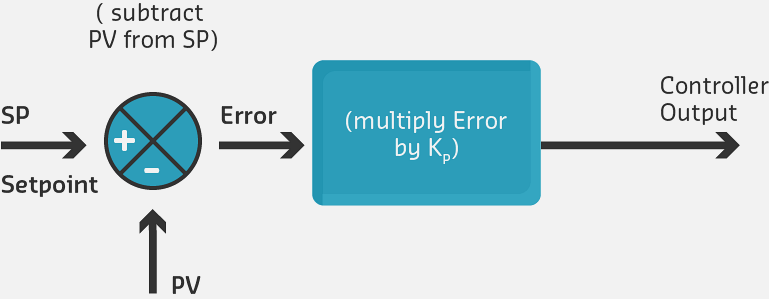

232.4 Proportional Control (P)

The Proportional term provides control action directly proportional to the current error. Larger errors produce stronger corrections.

\[ u_p(t) = K_p \cdot e(t) \]

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '16px'}}}%%

graph LR

Error["Error<br/>e t"] -->|Multiply by Kp| Gain["Proportional<br/>Gain<br/>Kp"]

Gain -->|Output = Kp x e t| Output["Control<br/>Output<br/>u_p t"]

Large["Large Error<br/>e = 5°C"] -.->|Kp=2<br/>Output=10| Strong["Strong<br/>Correction"]

Small["Small Error<br/>e = 0.5°C"] -.->|Kp=2<br/>Output=1| Weak["Weak<br/>Correction"]

style Error fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Gain fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

style Output fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

Proportional Control Mechanism: Output directly proportional to error magnitude. Large errors produce strong corrections, small errors produce weak corrections. Simple but may leave steady-state offset.

Characteristics:

- Fast response: Immediate reaction to errors

- Simple implementation: Single multiplication

- Proportional output: Big errors = big corrections; small errors = small corrections

Proportional Control Response:

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#ecf0f1', 'fontSize': '14px'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph Timeline ["P-Only Control Response Over Time"]

T0["t=0: Error Large<br/>Output High<br/>Fast Response"] --> T1["t=10s: Error Medium<br/>Output Medium<br/>Approaching Target"]

T1 --> T2["t=20s: Error Small<br/>Output Weak<br/>Slowing Down"]

T2 --> T3["t=30s: Steady State<br/>Small Error Remains<br/>Output Constant"]

T3 -.->|"Never Reaches<br/>Exact Setpoint"| T3

end

Problem["Problem:<br/>Steady-State<br/>Error Persists"] -.-> T3

style T0 fill:#E74C3C,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style T1 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style T2 fill:#16A085,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style T3 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,stroke-width:2px,color:#fff

style Problem fill:#E74C3C,stroke:#2C3E50,stroke-width:3px,color:#fff

Proportional-Only Control Timeline: Fast initial response due to large error, but as error decreases, control action weakens. System settles with persistent steady-state error because small remaining error produces insufficient control output.

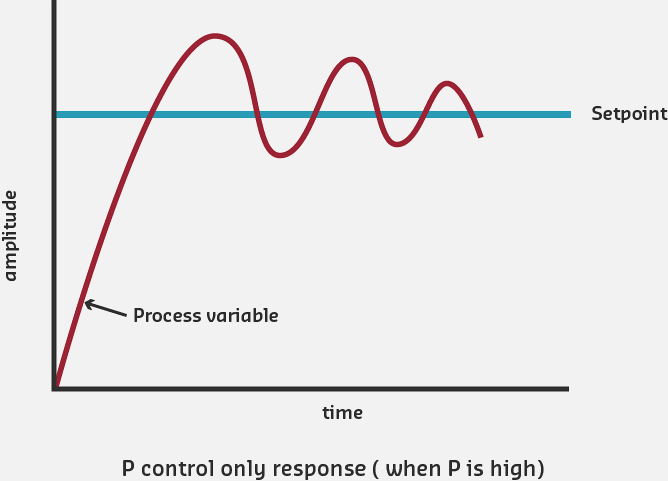

Problems with P-Only Control:

- Steady-State Error: System may never reach exact set point

- Overshoot: High Kp causes system to go past target

- Oscillation: High Kp can cause continuous cycling around set point

- Cannot handle disturbances: External forces cause permanent offset

232.5 Summary

In this chapter, we covered the fundamentals of PID control:

Key Takeaways:

PID Components: The three terms (Proportional, Integral, Derivative) each address different aspects of control - current error, accumulated error, and rate of change

Error Calculation: The foundation of PID is the error signal (e = SP - PV), representing the difference between desired and actual values

Proportional Control: Provides immediate response proportional to error magnitude, but cannot eliminate steady-state error

Kp Tuning: Low Kp gives slow response; high Kp gives fast response but risks overshoot and oscillation

P-Only Limitations: Cannot eliminate steady-state error or handle constant disturbances - requires integral term

232.6 What’s Next?

In the next chapter, we’ll explore the Integral and Derivative terms in detail, learning how they address the limitations of proportional-only control.