%% fig-alt: "Comparison of connected versus disconnected ad hoc networks showing connected network with four nodes having complete routing paths between all nodes, while disconnected network shows isolated node groups with broken paths and no connectivity between partitions"

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D', 'fontSize': '16px'}}}%%

graph LR

subgraph Connected["Connected Network"]

A1[Node A] ---|Path Exists| B1[Node B]

B1 --- C1[Node C]

C1 --- D1[Node D]

A1 --- D1

end

subgraph Disconnected["Disconnected Network"]

A2[Node A] -.->|No Path| B2[Node B]

C2[Node C] --- D2[Node D]

E2[Node E]

A2 -.->|Broken| C2

end

style A1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style B1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style C1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style D1 fill:#2C3E50,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style A2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style B2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style C2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style D2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

style E2 fill:#E67E22,stroke:#16A085,color:#fff

255 DTN Fundamentals and Store-Carry-Forward

255.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand DTN Concepts: Explain Delay-Tolerant Networks and their fundamental assumptions

- Analyze Disconnected Scenarios: Identify IoT applications where continuous connectivity is unavailable

- Apply Store-Carry-Forward: Implement the core DTN paradigm for intermittent connectivity

- Compare with Traditional Routing: Distinguish DTN approaches from connected ad hoc protocols

255.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should be familiar with:

- Ad Hoc Routing: Proactive (DSDV): Understanding proactive routing protocols helps contextualize why traditional approaches fail in disconnected networks and how DTN fundamentally differs from table-driven routing

- Ad Hoc Routing: Reactive (DSR): Knowledge of on-demand routing and route discovery mechanisms provides the foundation for understanding why DTN requires store-carry-forward instead of immediate path establishment

- Ad Hoc Routing: Hybrid (ZRP): Zone-based routing concepts introduce the idea of handling disconnected network partitions, which DTN extends with mobility and opportunistic forwarding

- Multi-Hop Fundamentals: Multi-hop networking concepts and relay node behavior are essential background for understanding how DTN leverages mobile nodes as data carriers

- Networking Basics: Fundamental networking concepts, addressing, and packet forwarding provide the baseline understanding for how DTN modifies traditional end-to-end communication

Imagine you’re trying to send a letter in a remote village with no postal service. Traditional networks assume you can call the post office anytime. But what if there’s no phone line? Delay-Tolerant Networks (DTN) solve this by treating communication like passing physical mail through travelers.

The Problem: No Connected Path

Traditional routing (DSDV, DSR, ZRP) assumes you can find a continuous path from source to destination. But imagine these scenarios: - Wildlife tracking: Animals roam miles apart with no fixed infrastructure - Rural villages: No internet connection, only a bus that visits once per day - Disaster zones: Infrastructure destroyed, only sporadic connections

In these cases, there’s NO end-to-end path at any moment. Traditional routing fails completely.

Store-Carry-Forward: The Post Office Analogy

DTN works like sending letters via travelers: 1. Store: Write your letter and give it to a passing traveler (they store it in their bag) 2. Carry: Traveler physically moves while carrying your letter 3. Forward: When traveler meets someone heading toward your recipient, they hand off the letter

Real-World Example: DakNet in rural India: - Villages have Wi-Fi kiosks but no internet - Farmers upload questions about crop prices to kiosk - Bus with Wi-Fi drives by twice daily, collects questions - At town, bus uploads to internet gateway - Responses downloaded to bus - Bus delivers answers on return trip - Latency: 24-48 hours (acceptable for non-urgent queries)

| Term | Simple Explanation | Everyday Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| DTN | Network that tolerates disconnections and delays | Mail delivery vs phone call |

| Store-Carry-Forward | Save message, physically move, then send | Carrying USB drive between computers |

When to Use DTN:

- Wildlife tracking (animals rarely meet)

- Disaster recovery (infrastructure down)

- Space networks (extreme delays)

- Rural connectivity (intermittent access)

- Video streaming (requires continuous connection)

- Real-time gaming (cannot tolerate delays)

Why This Matters for IoT:

Many IoT scenarios have intermittent connectivity by nature. DTN enables communication where traditional networking simply fails - you either use DTN or have no network at all! Understanding when to tolerate delays (hours) vs requiring real-time (milliseconds) is key to choosing the right IoT architecture.

Learning Resources:

- Simulations Hub: DTN simulators like The ONE Simulator for testing epidemic routing, spray-and-wait, and social-based protocols in realistic mobility scenarios

- Knowledge Gaps Hub: Common DTN misconceptions including “DTN is just slow networking” and “epidemic routing wastes resources” clarifications

- Videos Hub: Visual explanations of store-carry-forward paradigm, ZebraNet wildlife tracking, and DakNet rural connectivity case studies

- Quizzes Hub: Self-assessment questions on DTN performance trade-offs, utility function design, and protocol selection for intermittent connectivity

Why These Matter:

DTN routing challenges traditional networking assumptions. The Simulations Hub provides hands-on tools to visualize how messages propagate through disconnected networks. Knowledge Gaps addresses the misconception that DTN is simply “broken networking” - it’s actually a deliberate architectural choice for scenarios where continuous connectivity is physically impossible (wildlife tracking, rural areas, disaster zones).

Deep Dives: - DTN Epidemic Routing - Flooding-based DTN protocols - DTN Social Routing - Context-aware and social-based routing - DTN Applications - Real-world DTN deployments

Protocols: - Ad Hoc Routing: Proactive (DSDV) - Traditional proactive routing - Ad Hoc Routing: Reactive (DSR) - Traditional reactive routing - Ad Hoc Routing: Hybrid (ZRP) - Zone-based routing - Multi-Hop Fundamentals - Multi-hop communication

Architecture: - Wireless Sensor Networks - WSN in sparse deployments - UAV Networks - Aerial DTN applications

Learning: - Simulations Hub - DTN simulators

The Misconception:

Many students think DTN is simply traditional networking with high latency - like a slow internet connection. They assume DTN protocols are inefficient versions of TCP/IP that could be “fixed” with better routing algorithms.

The Reality:

DTN fundamentally differs from traditional networking in its assumptions about connectivity:

Traditional Networks (TCP/IP): - Assumption: End-to-end path exists when communication starts - Failure mode: Packets dropped if path breaks during transmission - Retransmission: Source resends if ACK not received (assumes path will reconnect) - Use case: Internet, LANs, cellular networks with continuous infrastructure

Delay-Tolerant Networks: - Assumption: No end-to-end path exists at any single moment - Acceptance: Disconnection is normal, not a failure condition - Store-carry-forward: Nodes physically transport data between disconnected regions - Use case: Wildlife tracking (animals 10km apart), rural areas (no infrastructure), disaster zones (damaged infrastructure)

Concrete Example:

ZebraNet wildlife tracking cannot use traditional TCP/IP because: - Zebras roam 5-20km apart (beyond radio range) - No cellular towers in remote African savanna - Battery budget: 3 years of operation - Data collection: GPS positions every hour

Why TCP/IP fails: Attempting TCP connection from Zebra A to base station fails immediately - no routing path exists. TCP gives up and reports “network unreachable.”

Why DTN works: Zebra A stores GPS data locally. When Zebra B passes within 100m (days later), they exchange buffered data. Zebra B later encounters Zebra C near watering hole base station. Data reaches researchers after 3-7 day delay, which is acceptable for migration studies.

Key Insight:

DTN isn’t “slow networking” - it’s intermittent connectivity networking. Latency isn’t a bug; it’s the price of operation where infrastructure doesn’t exist. The alternative isn’t “faster DTN” - it’s no communication at all.

When to Use: - No infrastructure possible (wildlife, disaster, space) - Communication can tolerate hours/days delay - Mobile nodes can carry data physically - Real-time requirements (video streaming, gaming) - Infrastructure available (use Wi-Fi/cellular instead)

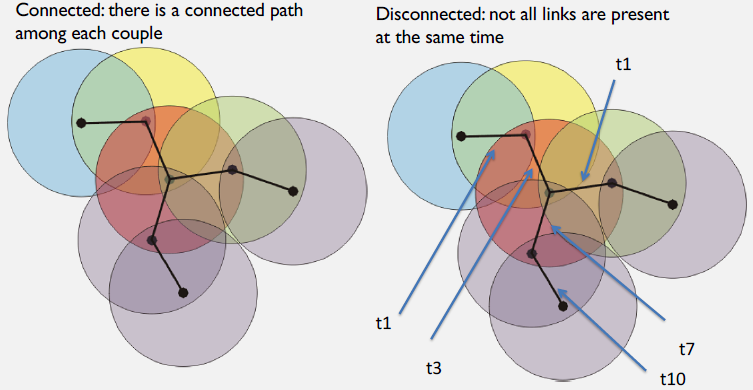

255.3 Disconnected Ad Hoc Networks

Traditional routing protocols (DSDV, DSR, ZRP) assume a connected path exists between source and destination. This assumption fails in many IoT scenarios.

255.3.1 Connected vs Disconnected Networks

Alternative View:

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

sequenceDiagram

participant SRC as Source<br/>Node

participant C1 as Carrier 1<br/>(Mobile)

participant C2 as Carrier 2<br/>(Mobile)

participant DST as Destination<br/>Node

Note over SRC,DST: Day 1: Source creates message

SRC->>SRC: STORE: Buffer message locally

Note over SRC: No path to destination exists

Note over SRC,DST: Day 2: First contact opportunity

SRC->>C1: FORWARD on contact

Note over C1: Carrier 1 now holds message

C1->>C1: CARRY while moving

Note over SRC,DST: Day 3: Carrier moves through network

C1->>C2: FORWARD to better carrier

Note over C2: Higher utility for destination

C2->>C2: CARRY toward destination

Note over SRC,DST: Day 4-5: Eventual delivery

C2->>DST: DELIVER on encounter

Note over DST: Message received!<br/>Latency: 4-5 days (acceptable)

%%{init: {'theme': 'base', 'themeVariables': { 'primaryColor': '#2C3E50', 'primaryTextColor': '#fff', 'primaryBorderColor': '#16A085', 'lineColor': '#16A085', 'secondaryColor': '#E67E22', 'tertiaryColor': '#7F8C8D'}}}%%

graph TB

subgraph Traditional["TRADITIONAL ROUTING (TCP/IP)"]

T_ASSUME[Assumption:<br/>Path exists NOW]

T_DISC[Route Discovery<br/>Find connected path]

T_SEND[Send Packets<br/>Hop-by-hop forward]

T_FAIL[Path Breaks?<br/>DROP PACKETS]

T_ASSUME --> T_DISC

T_DISC --> T_SEND

T_SEND --> T_FAIL

T_RESULT[Result: Fails in<br/>disconnected networks]

end

subgraph DTN["DELAY-TOLERANT NETWORKING"]

D_ASSUME[Assumption:<br/>NO path exists]

D_STORE[Store:<br/>Buffer in memory]

D_CARRY[Carry:<br/>Physical movement]

D_FORWARD[Forward:<br/>On contact]

D_DELIVER[Eventual Delivery<br/>Hours to days later]

D_ASSUME --> D_STORE

D_STORE --> D_CARRY

D_CARRY --> D_FORWARD

D_FORWARD -->|Contact| D_DELIVER

D_FORWARD -->|No contact| D_CARRY

D_RESULT[Result: Works across<br/>disconnected partitions]

end

style T_FAIL fill:#E74C3C,color:#fff

style T_RESULT fill:#E74C3C,color:#fff

style D_DELIVER fill:#16A085,color:#fff

style D_RESULT fill:#16A085,color:#fff

style Traditional fill:#7F8C8D,color:#fff

style DTN fill:#2C3E50,color:#fff

Disconnected Network Causes:

- Sparse node density: Nodes too far apart for single-connected component

- Node mobility: Moving nodes create temporary islands

- Sleep scheduling: Duty-cycling creates temporal disconnections

- Harsh environment: Obstacles, terrain block connections

- Failure: Node/link failures partition network

Traditional Protocols Fail: - DSDV: Can’t maintain routes across partitions - DSR: Route discovery fails if no connected path - Packets dropped at partition boundaries

255.3.2 Delay-Tolerant Networks (DTN)

Delay-Tolerant Networks enable communication across disconnected networks using store-carry-forward paradigm.

DTN Application Scenarios:

- Wildlife tracking: Animals carry sensors, transfer data when near base stations

- Vehicular networks: Cars carry messages between disconnected road segments

- Rural IoT: Mobile collectors (buses, delivery vehicles) gather sensor data

- Disaster recovery: Intermittent connectivity due to infrastructure damage

- Space networks: Planetary exploration with extreme propagation delays

255.4 Knowledge Check

Test your understanding of DTN fundamentals.

255.5 Summary

This chapter introduced the fundamentals of Delay-Tolerant Networks:

- Disconnected Networks: Traditional routing protocols (DSDV, DSR, ZRP) fail when no continuous path exists between source and destination, which occurs in sparse deployments, high mobility, sleep scheduling, and harsh environments

- DTN Paradigm: Unlike traditional networking that assumes connectivity, DTN assumes disconnection is normal and designs around it using store-carry-forward

- Store-Carry-Forward: The core DTN mechanism where nodes buffer packets locally (store), physically transport them while mobile (carry), and transfer them opportunistically when encountering other nodes (forward)

- Key Distinction: DTN isn’t “slow networking” - it’s intermittent connectivity networking where latency is the accepted price of operation in infrastructure-less environments

- Application Scenarios: Wildlife tracking, vehicular networks, rural IoT, disaster recovery, and space communications all benefit from DTN’s tolerance of disconnection

255.6 What’s Next

The next chapter explores DTN Epidemic Routing, covering flooding-based protocols that replicate messages to achieve high delivery ratios, along with optimization strategies like Spray-and-Wait and buffer management techniques.