326 Edge, Fog, and Cloud: Devices and Integration

326.1 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Choose Between MCUs and SBCs: Select appropriate hardware for edge/fog applications

- Design Three-Tier Data Flow: Plan data paths from things through fog to cloud

- Apply Integration Patterns: Implement protocol conversion and local processing

- Analyze Real-World Deployments: Learn from GE Predix and Amazon Go case studies

- Previous: Edge-Fog-Cloud Architecture - Three-layer theory

- Next: Edge-Fog-Cloud Advanced Topics - Worked examples

- Foundations: IoT Reference Models

326.2 Prerequisites

Before diving into this chapter, you should have completed:

- Edge-Fog-Cloud Introduction: Three-tier concept

- Edge-Fog-Cloud Architecture: Layer details

326.3 Basic IoT Architecture

A key component in developing an IoT solution is the computing platform that connects sensors to the Internet, processes or stores their data, and optionally actuates other devices. Often referred to as the “Processing” unit in IoT architectures, these platforms come in thousands of types—varying widely in capabilities, costs, and features. Practical questions commonly arise, such as:

- Which microcontroller or microcomputer should we use?

- How do we connect them to the Internet and “Cloud”?

- What is the difference between a microcontroller and a microcomputer?

Microcontrollers vs. Microcomputers

- Microcontrollers (MCUs):

- Typically single-chip devices combining a processor core, memory, and peripherals on the same integrated circuit.

- Designed for low-power, cost-sensitive applications; often run a bare-metal program or a small real-time operating system (RTOS).

- Examples: ARM Cortex-M series (e.g., STM32), AVR-based boards like Arduino, ESP8266/ESP32 modules.

- Microcomputers (Single-Board Computers or SBCs):

- Generally more powerful and support a full operating system (e.g., Linux, Windows IoT).

- Offer greater memory, storage, and connectivity options (Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth).

- Examples: Raspberry Pi, BeagleBone, NVIDIA Jetson boards.

The choice depends on project requirements: - Power Budget: Battery-powered sensors often favor MCUs for their low energy consumption. - Computational Needs: Tasks like advanced image processing or local AI inference may call for an SBC’s stronger CPU/GPU. - Cost & Complexity: For simple data acquisition, an MCU can be sufficient; for sophisticated applications, an SBC might be easier to scale.

Connecting to the Internet and Cloud

Whichever platform is chosen—MCU or SBC—the next step involves: 1. Physical or Wireless Interface: Ethernet ports, Wi-Fi modules, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), cellular modems, or specialized low-power protocols (LoRa, NB-IoT). 2. Networking Protocols: MQTT, HTTP/HTTPS, CoAP, or custom APIs to interact with cloud platforms. 3. Security Layers: TLS/SSL encryption, certificate management, secure bootloaders, and firewall or VPN tunnels to protect devices from attacks. 4. Data Handling: Designing how (and how often) the device sends data to the cloud and whether it receives downstream control messages, over-the-air updates, or configuration changes.

Three-Tier Data Flow: Things–Fog–Cloud

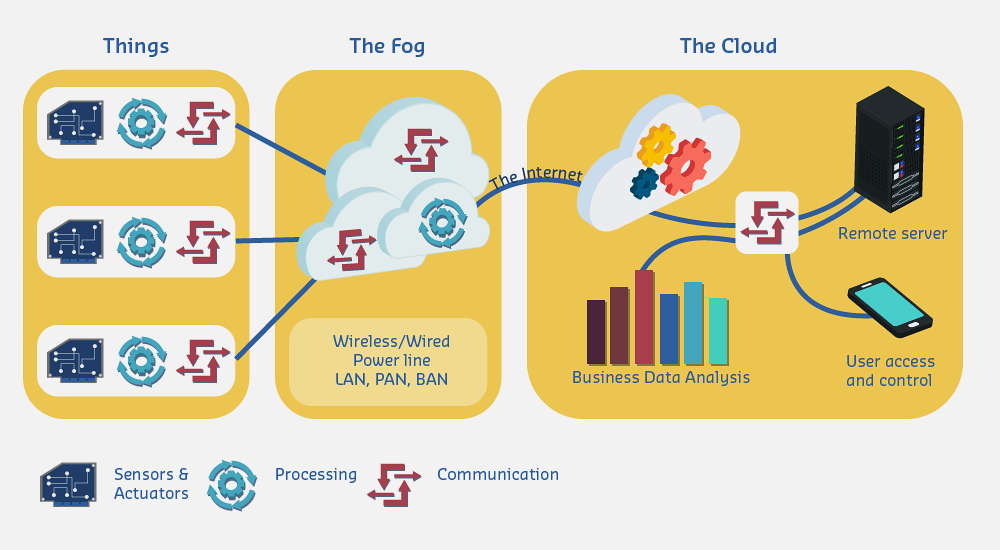

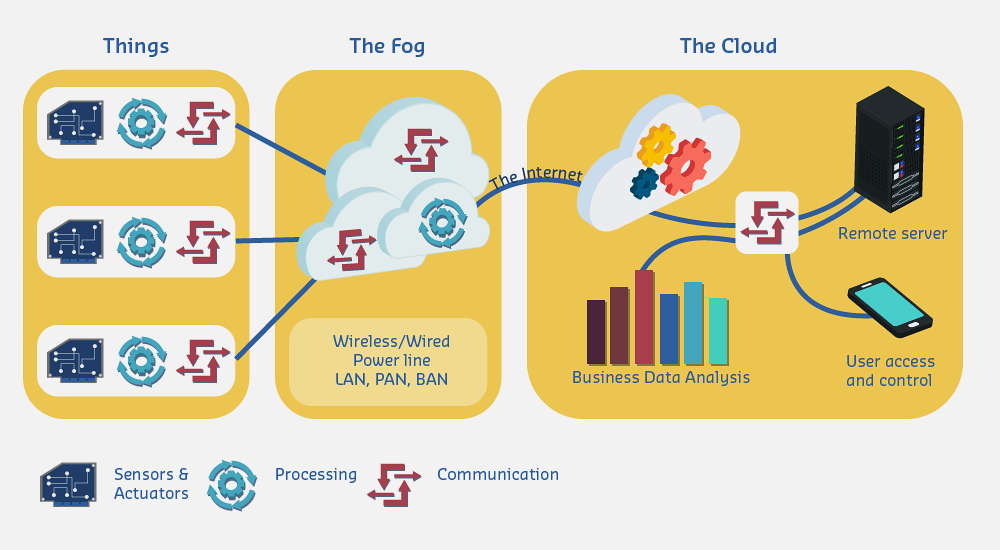

The following Figure depicts a typical three-tier structure:

When IoT projects grow large—incorporating numerous sensors and actuators—raw sensor traffic rarely flows directly to a distant cloud platform. Instead, intermediary devices (often called fog or edge nodes) sit between the field layer (where sensors and actuators reside) and the cloud. These intermediary devices aggregate data, execute local logic, enforce security, and optimize bandwidth by filtering or preprocessing the sensor stream. Figure fig-three-tier-model illustrates this three-tier model, highlighting the roles of each layer.

Things Layer

On the left side of the diagram, embedded boards integrate: - Sensors & Actuators (dark-blue icon): Interface with the physical environment by measuring temperature, motion, or light—or controlling motors, pumps, and valves. - Local Processing (turquoise gear): Convert analog signals to digital (A/D conversion), apply initial filtering, or run basic control loops. - Short-Range Communication (red arrows): BLE, IEEE 802.15.4, Wi-Fi HaLow, or even wired serial buses. Devices here are often power-constrained and focus on data generation, leaving long-distance data transmission or heavy analytics to higher layers.

Fog Layer (Intermediary Devices)

In the middle yellow panel, fog or edge nodes aggregate data from dozens—or even thousands—of field devices: - Protocol Conversion: Translating field-bus protocols (Modbus-RTU, CAN, Zigbee) into IP-based formats (MQTT, CoAP). - Pre-processing & Filtering: Removing noise, compressing payloads, generating local alerts, or buffering data during connectivity gaps. - Local Control: Handling latency-sensitive tasks, such as shutting a valve in milliseconds if sensor readings hit a critical threshold. - Multi-link Connectivity: Wi-Fi 6/7, 5G NR, Ethernet, power-line carrier. The label “LAN, PAN, BAN” indicates local and personal area networks, or even body area networks for wearables.

By pushing compute into the fog, systems shorten response times and reduce bandwidth requirements to the cloud.

Cloud Layer

On the right side, surviving data (i.e., post-filtered data from the fog layer) travels over the Internet to a public, private, or hybrid cloud, where resources are essentially scalable and on-demand: - Business Data Analysis: Large-scale time-series databases, streaming engines, AI/ML frameworks analyzing sensor telemetry for trends or anomalies. - Remote Servers: Hosting orchestration tools, device registries, digital twin models that mirror real-world devices. - User Access & Control: Web portals, mobile apps, APIs for dashboards, device management, and command issuance.

Cloud services provide near-unlimited capacity for long-term storage and multi-tenant analytics—enabling cross-domain integrations (e.g., combining IoT data with enterprise IT systems).

Bidirectional Flow and Control Loops

The double-headed arrows in the figure emphasize two-way communication: - Upstream: Device data, status reports, and event notifications flow from sensors and fog nodes to the cloud. - Downstream: Configuration commands, over-the-air firmware updates, and control signals originate in the cloud (or user apps) and pass back to the devices.

Closed-loop control can happen: - Locally in the fog layer, where real-time constraints demand immediate action (e.g., safety interlocks). - Remotely in the cloud, when detailed analytics inform decisions that aren’t time-critical.

This tiered approach—things, fog, and cloud—maximizes IoT’s efficiency, responsiveness, and security. The “Intermediary Devices” at the fog layer play a pivotal role, bridging diverse field protocols to powerful cloud services, while conserving bandwidth and enabling real-time local decision-making.

Industry: Aviation / Predictive Maintenance

Challenge: GE Aviation’s jet engines generate 1 TB of sensor data per flight from 5,000+ sensors monitoring temperature, pressure, vibration, and fuel flow. Early cloud-only architectures transmitted all data via satellite at $10-15/MB, costing $10-15K per flight. Worse, satellite transmission delays of 2-30 minutes prevented real-time anomaly detection, forcing reactive maintenance instead of proactive intervention.

Solution: GE implemented three-tier Predix edge-to-cloud architecture: - Edge Layer (Aircraft): Engine control units continuously monitor critical parameters (EGT, N1/N2 rotor speeds, vibration) at 10-50 Hz sampling rates - Fog Layer (Aircraft Gateway): Onboard gateway performs: - Real-time anomaly detection for critical thresholds (turbine overtemp, vibration spikes) - Data compression using proprietary algorithms (1 TB → 10 GB per flight = 99% reduction) - Feature extraction: FFT analysis of vibration spectra, statistical summaries of thermal cycles - Emergency alerts via ACARS if critical thresholds exceeded - Cloud Layer (GE Data Centers): Long-term trend analysis, fleet-wide analytics, ML model training for failure prediction across 13,000+ engines

Results: - 99% data reduction: 1 TB raw → 10 GB compressed telemetry per flight, reducing satellite transmission costs from $10-15K to $100-150 per flight - Real-time safety monitoring: Critical anomalies (compressor stall, bearing failure precursors) detected in <500ms by fog layer, triggering immediate cockpit alerts instead of waiting for post-flight analysis - Predictive maintenance accuracy: Cloud ML models analyzing compressed data predict component failures 10-30 days in advance with 85% accuracy, preventing 98% of unscheduled engine removals - Fleet optimization: Cross-engine analytics identified common failure modes across 47 aircraft, leading to $127M in warranty savings over 3 years

Lessons Learned: 1. Compress at the edge, not the cloud - Satellite bandwidth is expensive ($10-15/MB); compressing 1 TB → 10 GB saves $10K+ per flight versus transmitting raw data 2. Real-time processing requires fog - Safety-critical decisions (turbine overtemp) cannot wait for cloud round-trip; onboard fog processing provides instant cockpit alerts 3. Tiered analytics architecture - Simple threshold monitoring (edge), feature extraction and anomaly detection (fog), complex ML training (cloud) - each tier optimized for its role 4. Design for intermittent connectivity - Aircraft have limited satellite windows; fog buffers critical data for batch upload when connectivity available 5. Balance model complexity vs. deployment - Complex neural networks (cloud) vs. lightweight decision trees (fog) - fog models must fit in resource-constrained gateways

Industry: Retail / Computer Vision

Challenge: Amazon Go stores track 100-200 customers simultaneously using 1,000+ cameras and weight sensors across 1,800 sq ft. Processing all camera feeds in cloud would require 25 Gbps uplink (40 cameras × 1080p × 30fps × H.264 = 640 Mbps per store) costing $50K/month per location, with 100-300ms round-trip latencies preventing real-time inventory tracking (customers grab items and leave within 2-3 seconds).

Solution: Amazon deployed edge-fog architecture using custom hardware: - Edge Layer: 1,000+ cameras (overhead and shelf-level) and 2,000+ weight sensors continuously monitor store activity - Fog Layer: Local server rack with 50+ GPUs (NVIDIA Tesla) processes: - Real-time computer vision: person detection, pose estimation, hand tracking, object recognition - Sensor fusion: correlating camera data with weight sensor changes to confirm item selection - Customer tracking: associating items with specific shoppers as they move through store - Inventory updates: real-time stock level adjustments transmitted to cloud - Cloud Layer: Customer account management, payment processing, historical analytics, ML model training on anonymized shopping patterns

Results: - 99.7% bandwidth reduction: 25 Gbps raw camera feeds → 50 Mbps metadata (customer IDs, item SKUs, timestamps) transmitted to cloud - Real-time tracking: Fog processing achieves 50-100ms latency from item grab to inventory update, enabling customers to walk out immediately without checkout lines - Cost efficiency: Local GPU processing costs $12K/month (depreciation + power) vs. $50K/month cloud egress + $80K/month GPU instances = 85% cost reduction - Privacy preservation: Raw video never leaves store - only anonymized transaction metadata (customer ID, items purchased) transmitted to cloud for billing

Lessons Learned: 1. Latency-sensitive computer vision requires fog - Cloud processing (100-300ms round-trip) cannot track fast customer movements; local GPUs provide 50-100ms end-to-end latency 2. Privacy-by-architecture - Processing video locally and transmitting only metadata (SKUs, not faces) addresses customer privacy concerns and reduces regulatory risk 3. Economics favor fog for continuous video - Uploading 25 Gbps continuously is prohibitively expensive; fog processing eliminates 99%+ of data before cloud transmission 4. Hybrid training pipeline - Complex ML models (person re-identification, pose estimation) train in cloud on anonymized data, then deploy to fog GPUs weekly for inference 5. Scale fog horizontally - Amazon Go expanded from 1 store (2018) to 27 stores (2023) by replicating fog architecture, proving scalability of edge-heavy design 6. Fog enables new business models - Just Walk Out technology only feasible with fog processing; cloud-only architecture would be uneconomical

326.4 What’s Next

Continue to:

- Edge-Fog-Cloud Advanced Topics: Common misconceptions and worked examples

- Edge-Fog-Cloud Summary: Visual gallery and key takeaways